These days, Wonnerth Dejaco is full of cock. A fat rooster struts above the New York skyline, penis graffiti adorns one-dollar notes, and female figures rub, suck, and ride on a hand’s phallic fingers. “LUST,” the solo exhibition of activist, artist, and satirist Anita Steckel (1930–2012), is exactly what oozes from the mixed-media collages, archival material, and drawings on view at the gallery: for sex, for provocation, for tongue-in-cheek – or tongue-on-dick – imagery. Especially memorable are male genitalia drawn on xerox copies of the artist’s face, her lips gleefully pursed on an acorn, her wide-open mouth welcoming jizz from four hard, neatly arranged penises. Looking at the raw images, I almost feel the cold glass of the copier and my damp breath on it. The prints are mounted on “well-behaved,” crafty wallpaper with flowery ornament, standing in downright silly contrast to the copies’ dirty contents and sketchy quality. The message is clear: I don’t want flowers, but dick – also exposed in grand museums.

For several years, curator Juliette Desorgues has been working on Steckel’s first exhibition in Europe – part of Vienna gallery festival curated by. The artist was integral to the downtown scene in 1960s and 70s New York and, alongside Judith Bernstein, Louise Bourgeois, Joan Semmel, and Hannah Wilke, a member of the “Fight Censorship Group,” which resisted the oppression of female sex-positive work. (Steckel co-founded the group following the attempted censorship of her 1972 exhibition “The Feminist Art of Sexual Politics” at Rockland Community College on the grounds of obscenity.) Her work was largely underrepresented in her lifetime, her CV lacking any major solo exhibitions, though attention has recently been revived by shows at Stanford Art Gallery and Hannah Hoffman Gallery, both in Los Angeles.

View of “LUST,” Wonnerth Dejaco, Vienna, 2023. Photo: Peter Mochi

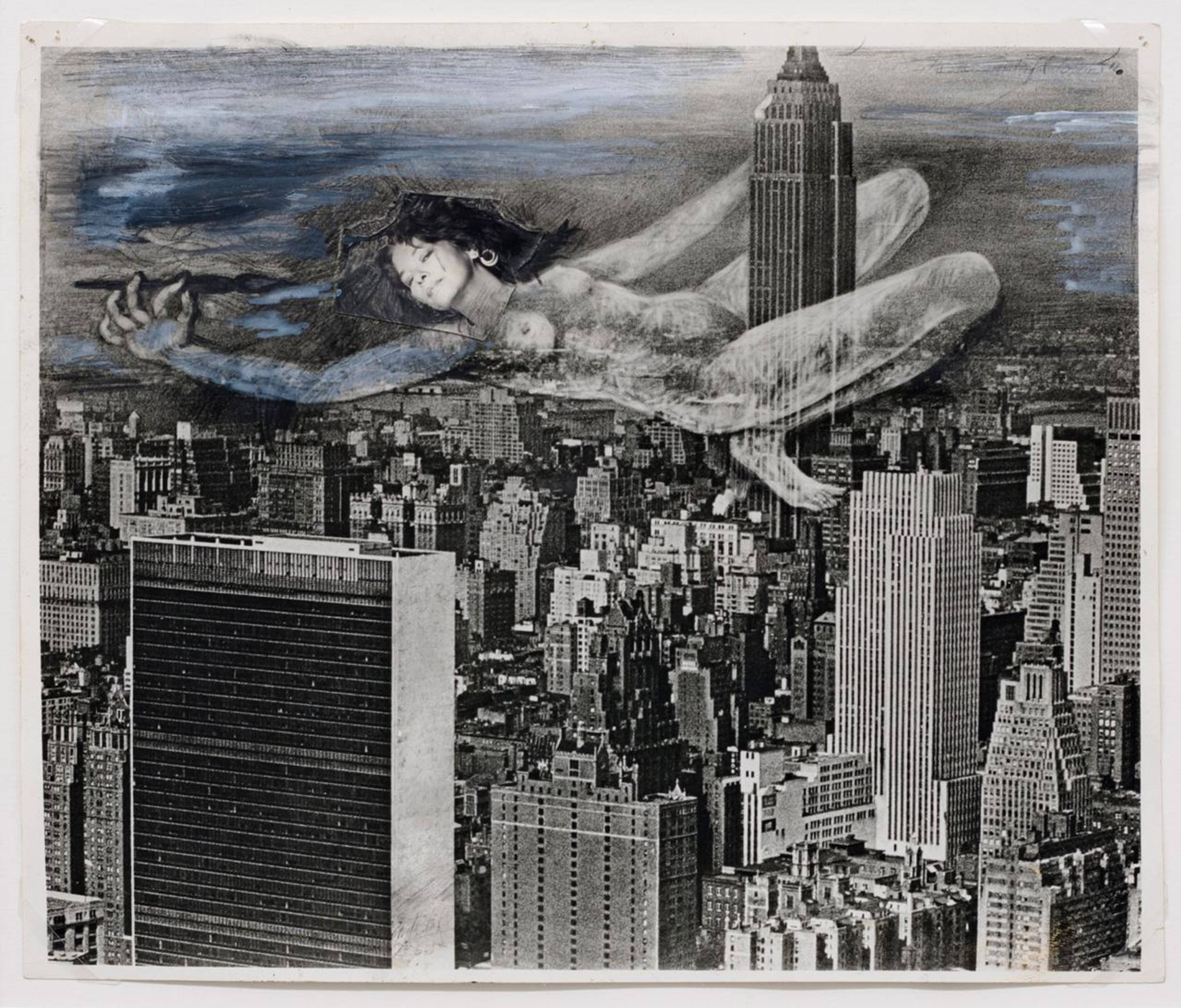

Steckel’s works are joyfully brute, fast, and empowering: Her business card shows the Mona Lisa holding a paint brush, one boob hanging out in front of Manhattan. Female potency’s takeover of city space is likewise the main theme of “Giant Women on New York” (c. 1969–74), a major series of drawn-on, collaged, and painted-over photographs. Empire State (1974), for instance, depicts a glorious female nude scissoring the phallic building, though “LUST” only shows its preparatory sketch, while unfortunately leaving out altogether the series’ more ambivalent and vulnerable works.

The artist examined the phallus not only as an object of pleasure, but also as a patriarchal apparatus. The print Bring it on (c. 2004–08), a depicts George W. Bush with a cross over his crotch and is subtitled “macho christianity.” The dick-pic’d dollar bills, which were distributed at the opening of “The Feminist Art of Sexual Politics,” are overwritten with “Legal Gender,” hinting at the pay gap. Steckel’s work remains pressingly vital in its questioning of embodied gender’s contradictions: What does it mean to desire the oppressor’s body? And how should straight women deal with the contradictions between empowerment and pain? At the same time, and despite Steckel’s pioneering historical role, the liberational force and provocative potential of the erect penis seem both worn out and somewhat blind to marginalized positions in sexual politics today. (It should be noted that “Fight Censorship Group” was entirely white, cis-gendered, and heterosexual.)

Preparatory collage for Empire State (Giant Women on New York), c. 1969–73, collage on silver gelatin print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm. Photo: Peter Mochi

Anita Steckel, Untitled, n.d., print on paper, 28 x 21.5 cm. Photo: Dario Lasagni

More interesting perhaps is Desorgues’s invitation of two contemporary writers to converse with the show. The air was tense to bursting during Constance Debré’s reading from her auto-fiction Love me Tender (2021), a powerful self-examination of lesbian desire and motherhood. The novel’s protagonist leaves her family and law career, shaves her head, and tattoos “son of a bitch” across her belly, becoming a butch artist who spends her “lonesome cowboy” time writing, swimming, and craving sex. The dissolution of the bourgeois family – the protagonist loses custody for her son on the grounds of “obscenity” – and the evolvement of queerness as a rejection of societal conformity and material security is told without no bra, deodorant, or ornament. Whereas Debré shares Steckel’s crude, slap-in-the-face language, artist and political dominatrix Reba Maybury’s writing reaches for play to deal with sexuality and challenge the museal space with perversion and desire. Reading from the opening chapter of a forthcoming book, Maybury asks a man in the audience to play a submissive that Mistress Rebecca meets in a bar, charging the gallery event with improvisatory surprise. Her writing is hilarious, but also ironically and sharply critical in its observations, using her practice as a sex worker to infuse art with questions of power relations, labor, and female strength.

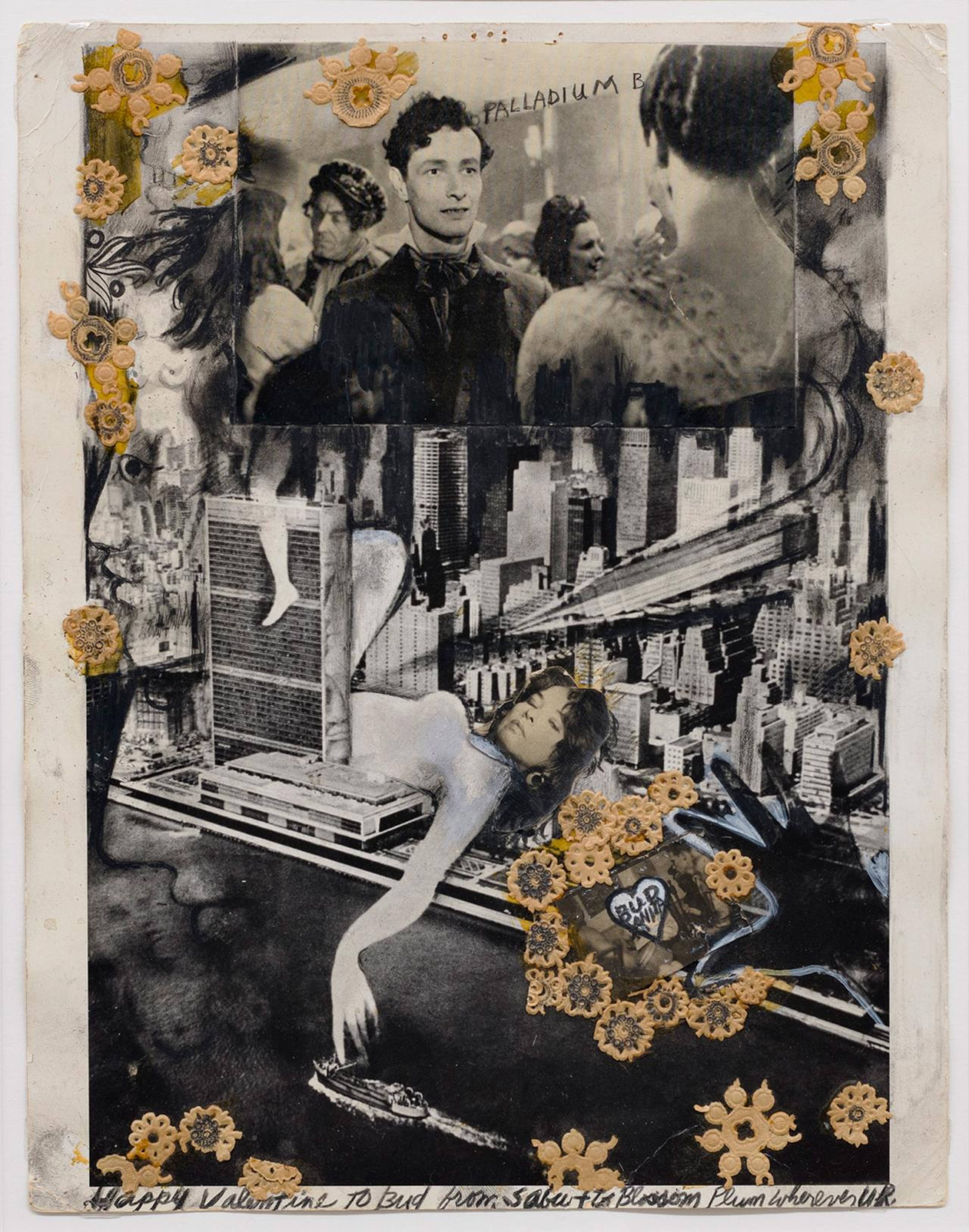

The radicality of Debré and Maybury’s approaches lies in the relentless dissection of their own experience; like Steckel, they dare to address their political and artistic concerns with “I.” Besides founding the “Fight Censorship Group,” the puritanical shitstorm caused by her 1972 exhibition prompted the author of “Giant Women” to rework the series, collaging her own face onto the originally anonymous figures. Because what might take more guts than exposing the erect penis? Exposing the living self.

Anita Steckel, Preparatory collage for Valentine to Brando (Giant Women on New York), c. 1969–73, photo collage, 28 x 20.5 cm. Photo: Peter Mochi

___

“LUST”

Wonnerth Dejaco, Vienna

8 Sep – 14 Oct 2023