“Can one ‘be’ against war in one’s body while wholly bound up in complicity with it? // While using its language? // While using its language against oneself?” These central questions drop a pin at the twin suns around which orbits the most recent poetry of Ariana Reines. Astrologer, the poet is sorting through not just the signs of the world, through material of the actual, but through literal and metaphorical blood – of the dead, of the maimed, of the menstruating, of family bonds – for how to be, how to care, how to remain open.

Near the end of Wave of Blood (2024) – a relentless chronicle of mourning (for her mother, for Palestine, for vital, open-hearted works of art “that are pervaded by a consciousness,” as well as an unlikely version of an “operating theater” where the poet is doing something “like performing field surgery on [her]self” – Reines writes that she “wasn’t actually living anywhere” and “was finishing a book called The Rose [2025]” – a book “about the question of the erotic mistake.”

With these two books, deeply entwined by time, by bodies and actions and language, the poet keens and romances, keeping “sorrow undefiled by words,” and trying to rally to a mentor’s advice that “Laughter // Was the only way to get through times like these.” The paradox of conjunction – sorrow and laughter: “My body knows two words / & two words only: // Yes & No.” The ampersand insists: To keep open is a question not of or, but of ore. The books are magnanimous examples of the soul selecting its own society (“If you fail to build in yourself a secret / Room the culture will simply / Conduct its cargo & traffic up / & down you: you’ll begin / To feel like an airport”), as well as attending to the other, providing shelter where there has been none. There, Reines rendezvouses with the angel of history and works with-in the magma of the moment.

Chordal and according, of course the two new books are entwined, because how could they not be? We may not condone the current excruciation called a world, we may not have “chosen” it, we may “refuse” it. And yet, in Wave of Blood:

We are giving up caring for ourselves and for each other.

We are watching the slaughter we pay for, and we are giving ourselves away in the process …

Which The Rose somehow answers:

how can it be said?

I don’t “have ideas about” catastrophe

it’s just my body. theory of the flower

we only care about what we can see …

who is “we”?

me again, obviously

While it is entirely possible to read these books separately, I’m not sure what the benefit would be, since they compel thinking through the same impossible, inconsolable fact of life’s brutality, its bleeding, as it is freaked by pleasure, even mistaken pleasure. Slam that into reverse: fact of life’s pleasure, its blending, as it is freaked by brutality. They gloss one another, and not merely. “My aim had been to avoid memoir, but I need to describe some of the entanglement through which this effort – this book – arose.” The Rose’s arising within Wave of Blood. “They make you / Believe your death is worth / Something. & your life, nothing – when nobody else // Is brought to justice you yourself become available / For punishment.”

2.

The illusion that language could be a shield against the monstrous was, for me, among the first to be shattered and destroyed. Language is not immune to acts of genocide and annihilation. It, too, can be destroyed, become unable to endure, get lost. I had never felt myself to be a master of language – more that language had mastered me. And accepting its brokenness, its actual feebleness, has allowed me to continue working through decades of the pain and injury inflicted on Palestine.

— Adania Shibli, 2025, in conversation with Max Weiss

From The Rose:

Tell me how a woman

Can enter heaven

& bring its riches down

How water can be made to flow in the desert

How a soul can be stripped bare in the underworld

How birth can be given – even in the underworld –

How order can be restored between earth & heaven –

How this is done partly through delight. & partly

Through the laying-bare of your own soul.

& partly through the harmonizing of your feeling

With what flows already – naturally – through the water & the wind

& the lettuce that grows beside the water

& the milky nectar in its flesh. How

All at once you do this: how in a flash you know how.

Even an ancient seed

Can fertilize me in this polluted world.

Nobody

Taught me this. It occurred

To me.

From Wave of Blood:

I think this is part of the instruction of this moment, to reckon with these paradoxes of our culture and our own lives, and to develop the agility – we who have the privilege of not having bombs falling on our heads and not literally being the ones physically dropping them – to develop the agility to find something to respect, inside ourselves and outside ourselves, and to hold high. The diamond of the mind itself – in spite or irrespective of its atmosphere.

Some days this is seemingly impossible, exhausting.

3.

In her line breaks, her poetic “lines / Of work,” precise as Vedic calculations, Reines commits herself “ruthlessly to action.” This “Rilke in reverse” – here in conversation with and working through Dante, Milton, Baudelaire (“L’Amour et le crane” and Mon coeur mis à nu), Francis Ponge (Le Savon and “Le soleil placé en abîme”), James Merrill, Etel Adnan, T.S. Eliot (the shore and shards of language’s littoral breaking point at the end of The Waste Land translated to “broken pottery. Poetry?”) with which she tiles a pool and tills – takes up the challenge of becoming woman, of the one womb, mater matters, and what “pulled / Europe out of the dark ages / Might’ve been a turn / In the addressee / Of poetry. When it turned / Toward the woman.” All of these things could be too quickly relegated to the literary, when, really, they are thornily of life.

With such entanglements, Reines aims to meet the baroque, innovative, core-structuring achievement of Catalan musician, conductor, composer, and scholar Jordi Savall’s album Les Voix humaines. “This record sounds like everything I want to do,” she writes; why?

… when he plays I can hear not only the triumphs of Reason but a profound experience of its nightmares, to paraphrase Goya.

For me Savall is an example of leadership, death, the paternal and masculine principle functioning properly – knowing its history and being honest about it. Fulfilling his role with flair – without erasing mystery, or tragedy.

And yet: “I have been searching for a way to speak accurately and protest accurately that does not masculinize me, that does not find me hardening my speech into the eroticized militancy of the noble freedom fighter.”

All of it deserves so much more attention, and it shouldn’t feel as strange as it does to focus in on the poetry, on Reines’s writing, which is both nakedness and undertaking.

The Rose’s opening poem, “( )”, calls to the double-spaced lines on the final page of Wave of Blood, their evocation of Eden, God, the citrus of Palestine – which, as a vivid student pointed out to me, could be the fruit that was transmuted into Eve’s infamous Apple.

Dressed as a puritan

She picked a lemon off the ground

Green on one side

As the early womb

Wrapped in cloud

Was accused of having been full

Of fire. Two halves

Of the root of all things

Are touching in a lewd

& unstoppable way – leaking

Organ-pink light

More life than we know what to do with

In costume as the author of Paradise Lost, puritan who would have sided with the witches in Salem and not the lesser, mendacious Puritans, “she” harvests a sun, at once Mother Nature, early green galaxy spinning in the palm of her hand, and Dürer’s Melencolia I. The point-blank of all things touching lewdly, unstoppably, leaking radiance, aurora. Then that last line in Reines, one of the sharpest thorns among the poem’s many astonishments: It isn’t more death – genocide or environmental devastation – that we don’t know what to do with; it’s life, and that horrific paradox, accelerated by algorithmic tech and crypto-capital, doomscrolling to the nth degree, is what we must work against, each by their means.

___

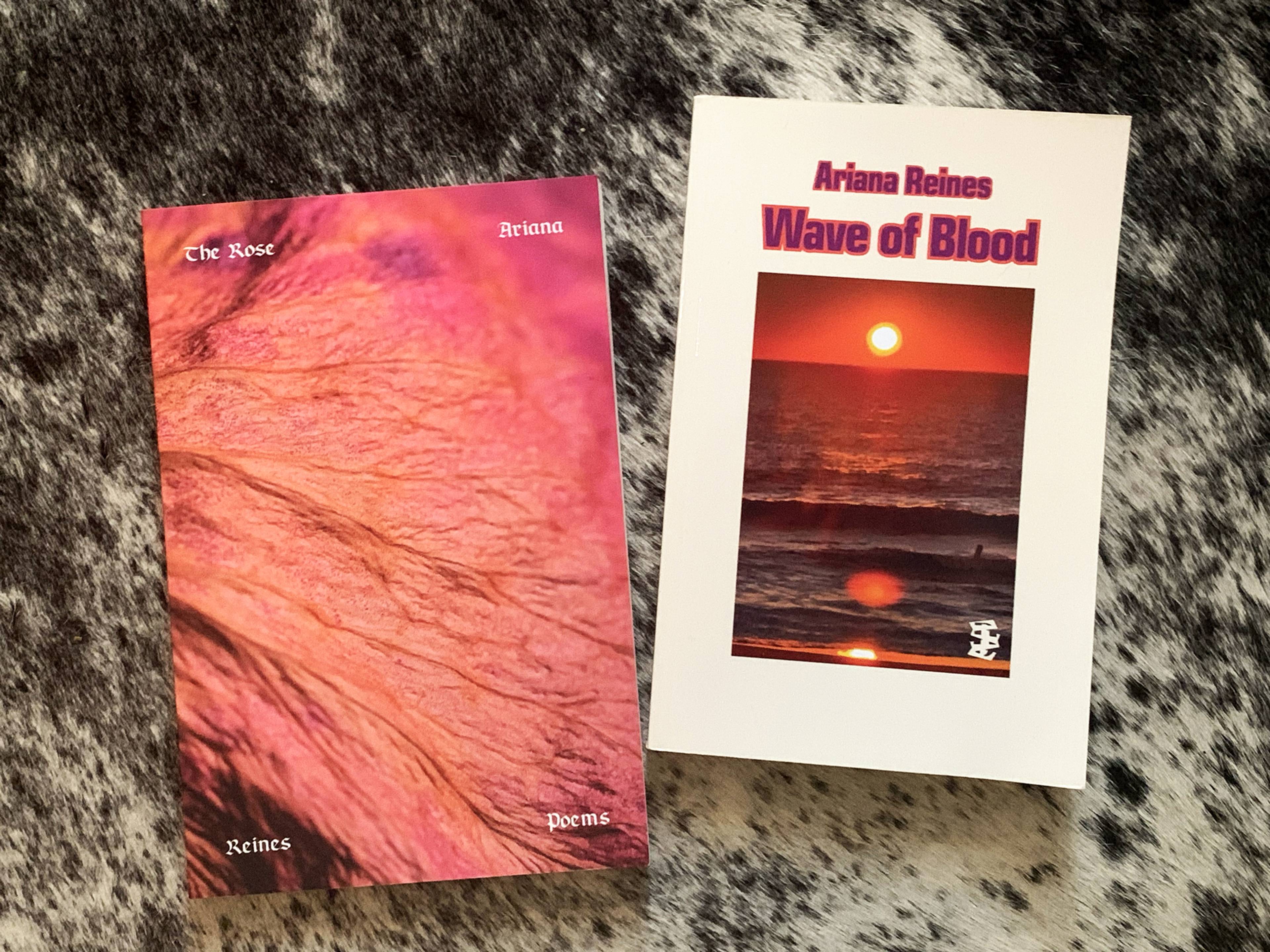

Ariana Reines’s latest books, Wave of Blood (2024) and The Rose (2025), are published, respectively, by Divided Publishing and Graywolf Press.