A life is a complex litany of conjoined clauses that only gets punctuated in its retelling. Cathy Josefowitz (1956–2014) lived a life of radical practice, one that ran in many directions. She worked in dance, performance, set design, and music, but most of the 3,000 or so works she created across four decades (only a fraction of which were exhibited in her lifetime) are drawings and paintings. And where there is now a beginning, middle, and an end to this story, there was once a life’s restless pursuit of consummate self-expression.

Born in New York, Josefowitz grew up chiefly in Geneva, with long spells in France, Italy, and the UK. Not a prominent artist in her own lifetime, this survey is her first with Hauser & Wirth, who now represent her estate. If it is romantic to imagine that public recognition was not what drove her, one also wonders if she could have made such a heterogeneous body of work unless she was, to a degree, free of the seismic pressures of success and its demands for a recognizable artistic consistency. Once she broke through her early influences, much of her output is urgently and enviably unselfconscious, a quality that seems ever harder to achieve in a digital age that is constantly eating its own face.

View of “Release,” Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, 2024. All images: © Estate of Cathy Josefowitz. Courtesy: Estate of Cathy Josefowitz and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Jon Etter

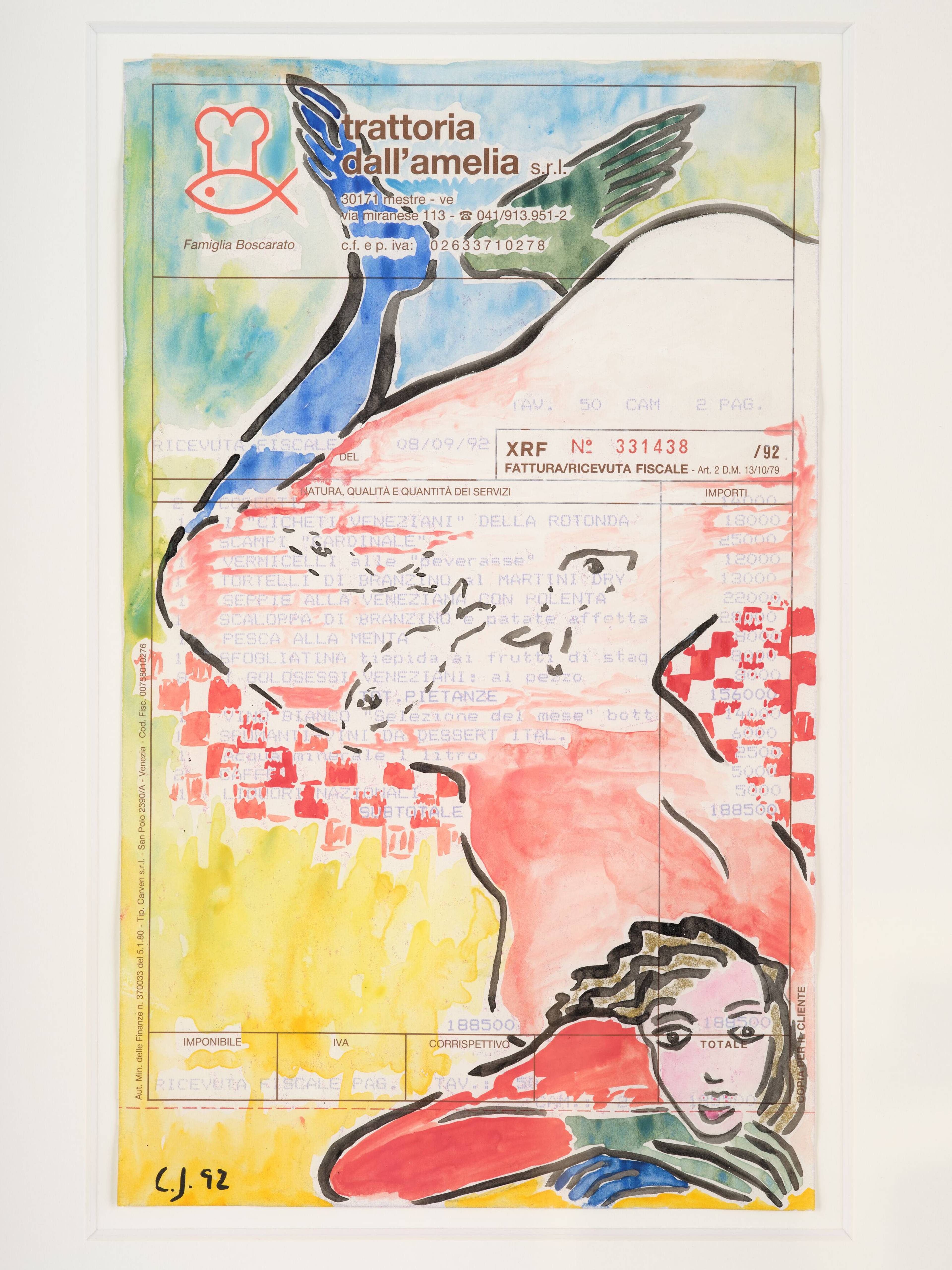

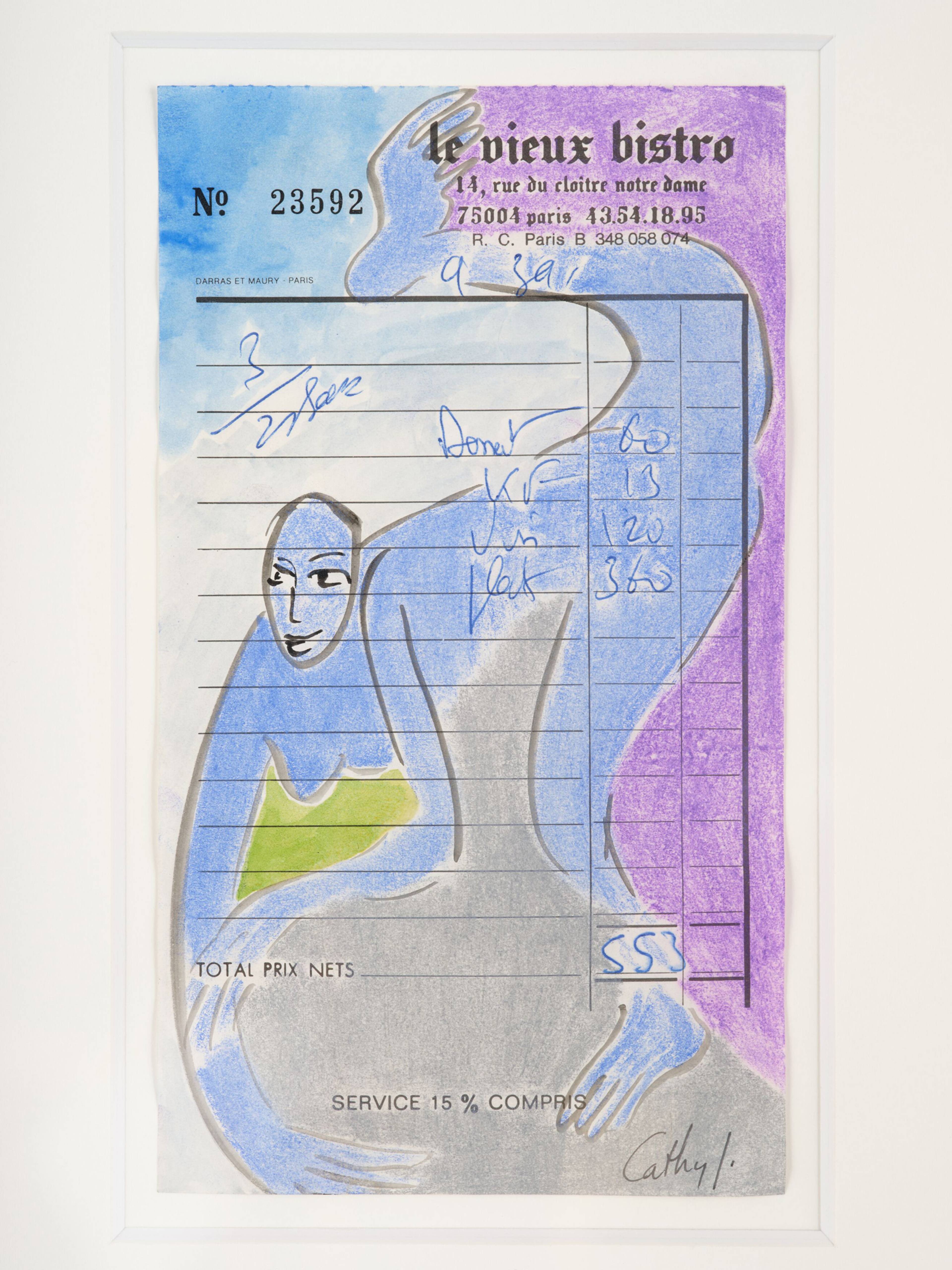

It is a challenge to slice a life’s work into such a thin cross section, and yet, Josefowitz’s work, with its experiments, diversions, and common threads, lends itself well to such treatment. The beginning of her career found her grappling with the long shadow of her Modernist heroes. Early works on cardboard show an aesthetic interest in painted patterns, fragmented nudes, and circus figures where the influences of Picasso and Matisse loom uncomfortably large, as they did for many of her generation, Yet, the first room ends with a series of watercolor ink on restaurant receipts (1988–92), which show a gorgeously subversive, punk-rock wit in bloom. Her figures drip and sprawl with cartoonish joy across these bills’ stuffy letterheads, her marginalia a kind of anti-admin, carnivalesque gesture against a capitalist society that insists on reducing every sensual experience to its own scentless system of value.

Posthumous retrospectives present a particular risk to critique, as the narrative being presented is a pre-mapped terrain, and yet, one also has an abiding sense that the artist herself was entirely unconcerned with what might make a good tale, so committed was she to her own tides of experimentation. An initiatory urge to draw unfolded into theater design, then painting, then experimental dance and protest music, stinted by a brief foray into midwifery. At the Darlington College of Art in the early 1980s, she encountered “contact improvisation” and the “anatomical release technique” of choreographer Mary Fulkerson. Josefowitz’s short film Release (1988) finds her falling, writhing, and throwing her body through space to break down physical inhibitions, an exploration of the metaphysical through the anatomical that plays throughout her drawings and paintings of figures. The body is her red thread, and the bulk of her corpus confronts the corporeal, a figuring out by thinking through the figure. She wanted to paint the body as it is experienced, transcribing that costume of sensations across whose frontiers our inner and outer lives meet. A bodily intuition prevails,, her later works in particular eliciting her fascination with contact improvisation’s “safe falling.”

Trattoria dall’Amelia – Mestre, 1992, watercolor and ink on paper, 25 x 15 cm. Photo: Jason Klimatsas

Le Vieux Bistrot - Paris, 1991, watercolor and ink on paper, 17.6 x 9.9 cm. Photo: Jason Klimatsas

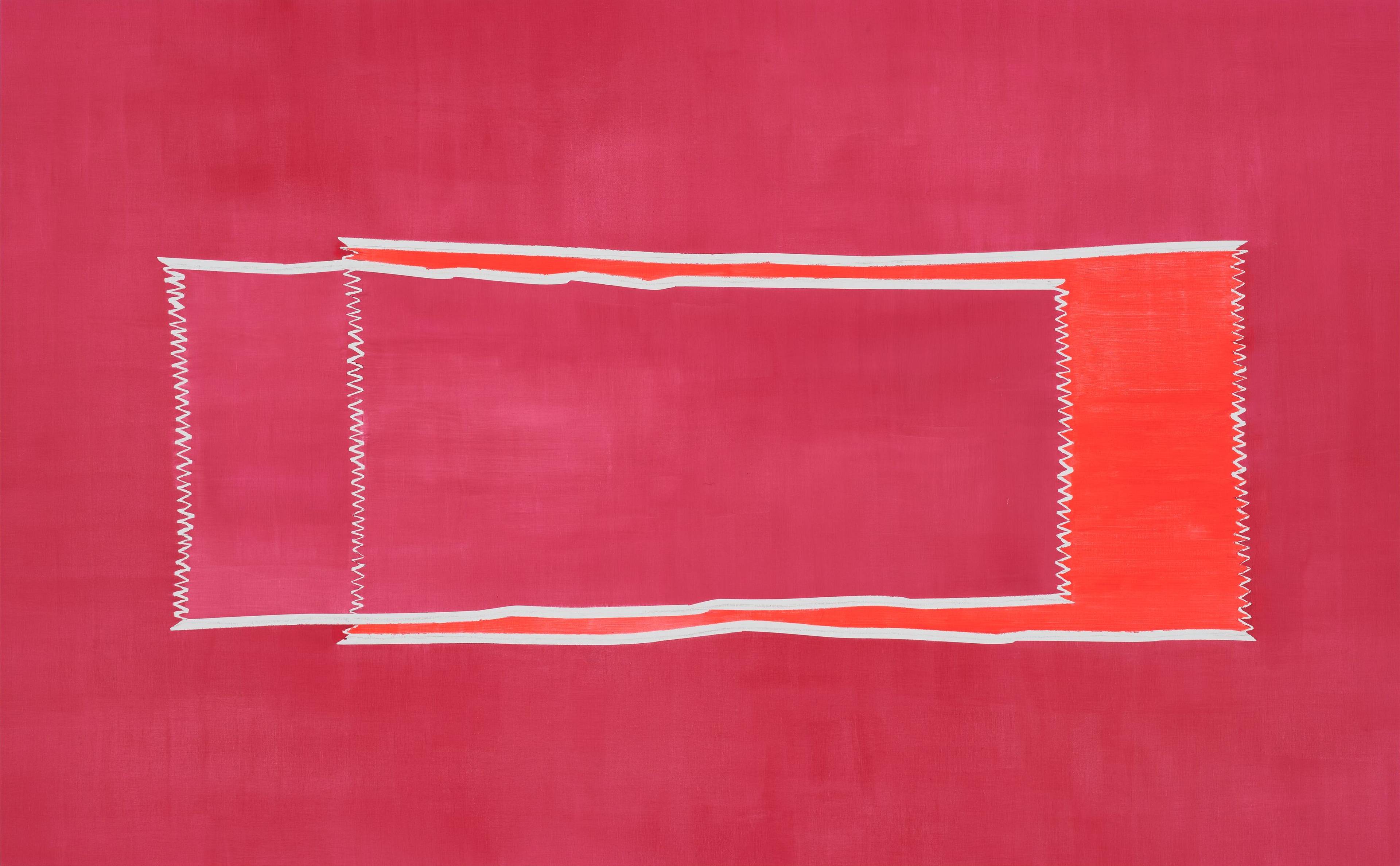

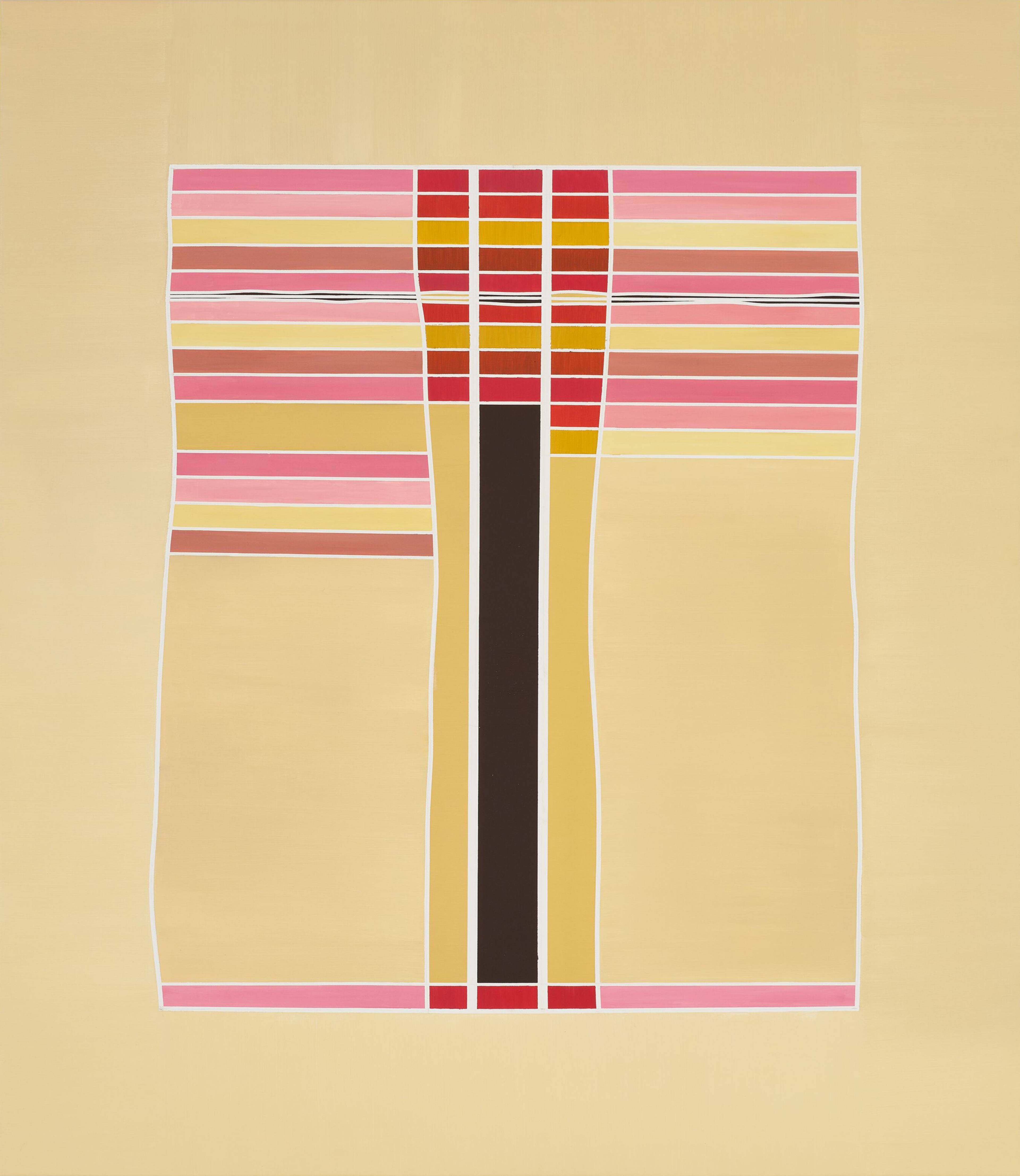

Even when the paintings evolve into abstraction in the “Prayers” series (1988–2001), their shawls and rugs, suspended in monochrome expanses, have a human dimension. Forced to paint on the floor for lack of wall-space, the forms captured are a result of letting the material fall across the canvases in a kind of danced motion and then tracing their resulting shapes; a divinatory form of her own devising. They also texturize Josefowitz’s long-held interests in different mysticisms, her sacred geometries invoking that veil that separates us from the hidden, this world from the next.

Returning to figuration in the “Venus” series (2004–06), these plains of distilled color become the context for a succession of female figures who appear to be perpetually falling; skydiving bodies unanchored from the physical world. Here, she co-opts her art-historical references: In reclining nudes “after” Manet and Titian, it is as though a light has been switched on inside each figure, and we can no longer make out their features though the glare; this is the gaze reversed, the nude as something transcendent and incorporeal.

Parme, c. 2001, oil on canvas, 202 x 325 x 3 cm. Photo: Jon Etter

Untitled, c. 1998, oil on canvas, 227.1 x 196.5 x 2.7 cm. Photo: Jon Ette

One of the few works with its own title, Dans la forêt (In The Forest, 2004) closes the show with an archaic other-worldliness. Standing nearly two meters high, its wide-eyed, pencil-rendered figure confronts a headless apparition, whose bloodied robe contrasts with the groundless, deep-green colorscape. It is an unsettling scene, death and the maiden reimagined, or an honest annunciation that captures the actually terrifying idea of an immaculate conception, or the artist in a violent reckoning with her unborn legacy.

___

“Release”

Hauser & Wirth

1 Feb – 17 May 2024