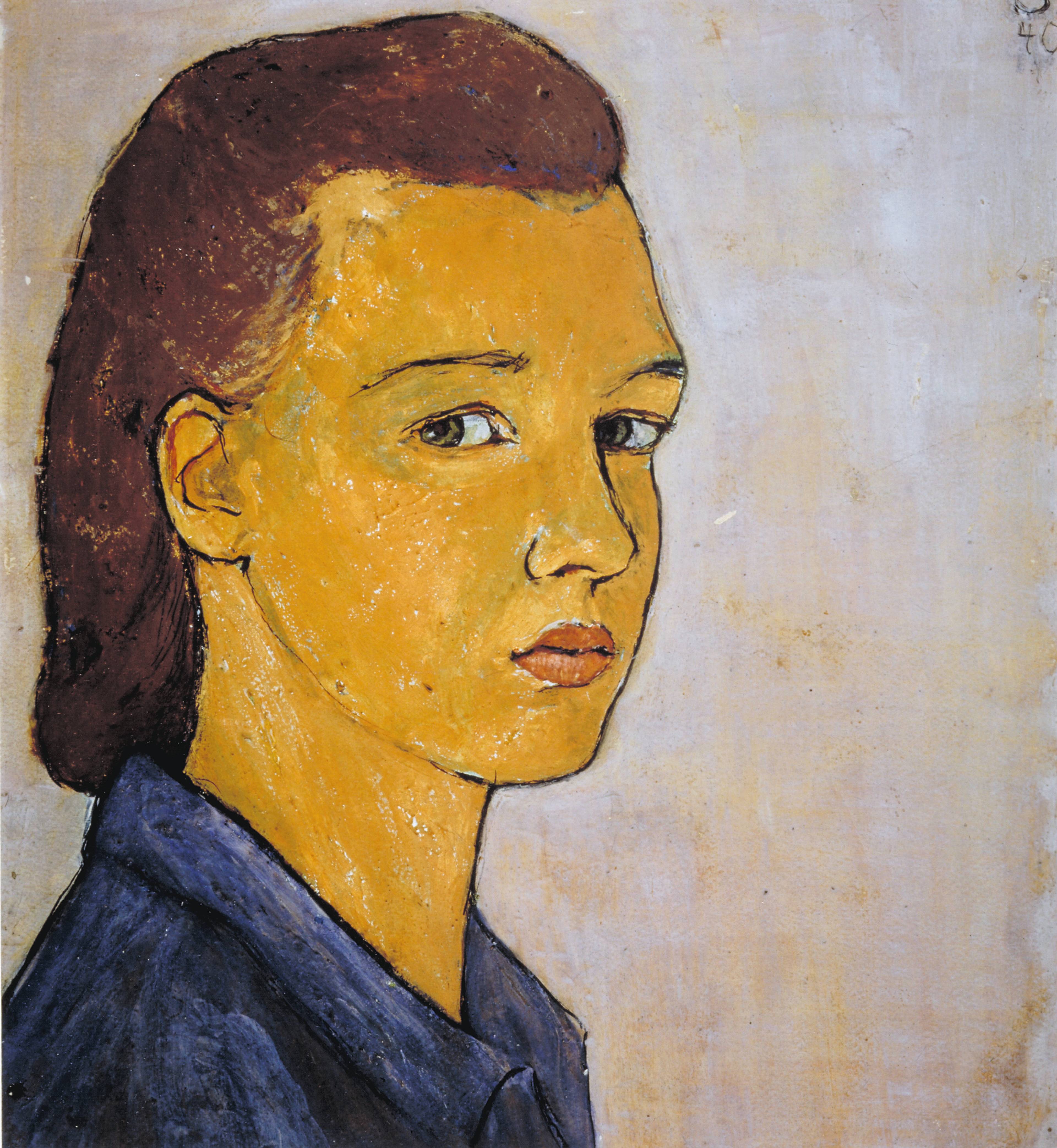

Wandering through the exhibition of an artist who died young in Auschwitz, one cannot avoid a biographical view of the artwork, even in a present tense when “personal narrative” has entered the critical vocabulary to such an extent that its use has become a lazy tic. Yet autonomy or self-reflexivity seems to be an equally empty appeal.

Charlotte Salomon (1917–43), then, comes to us at just the right moment, as a regenerative model of how to play with biography: with ironic distance, in the form of a singular tragicomedy. Between 1940 and 1942, the artist conceived and produced an impressive variety of gouaches on paper (769!), all of the same 32.5 x 25 cm format, mostly sequentially arranged to tell the pictorial Singspiel (song-play) Life? or Theater? , now on view in the Lenbachhaus Kunstbau in Munich. In a form at once expressionistic and grotesque, Salomon tells the story of her alter ego, Charlotte Kann, a Woolf-ish Orlando fragmented into others, a fictionalized version of herself living in a big city, the small and large events of a life interwoven with those of so many other people – family members, friends, friends of friends – who appear in the here and now or through glimpses in digressive flashbacks.

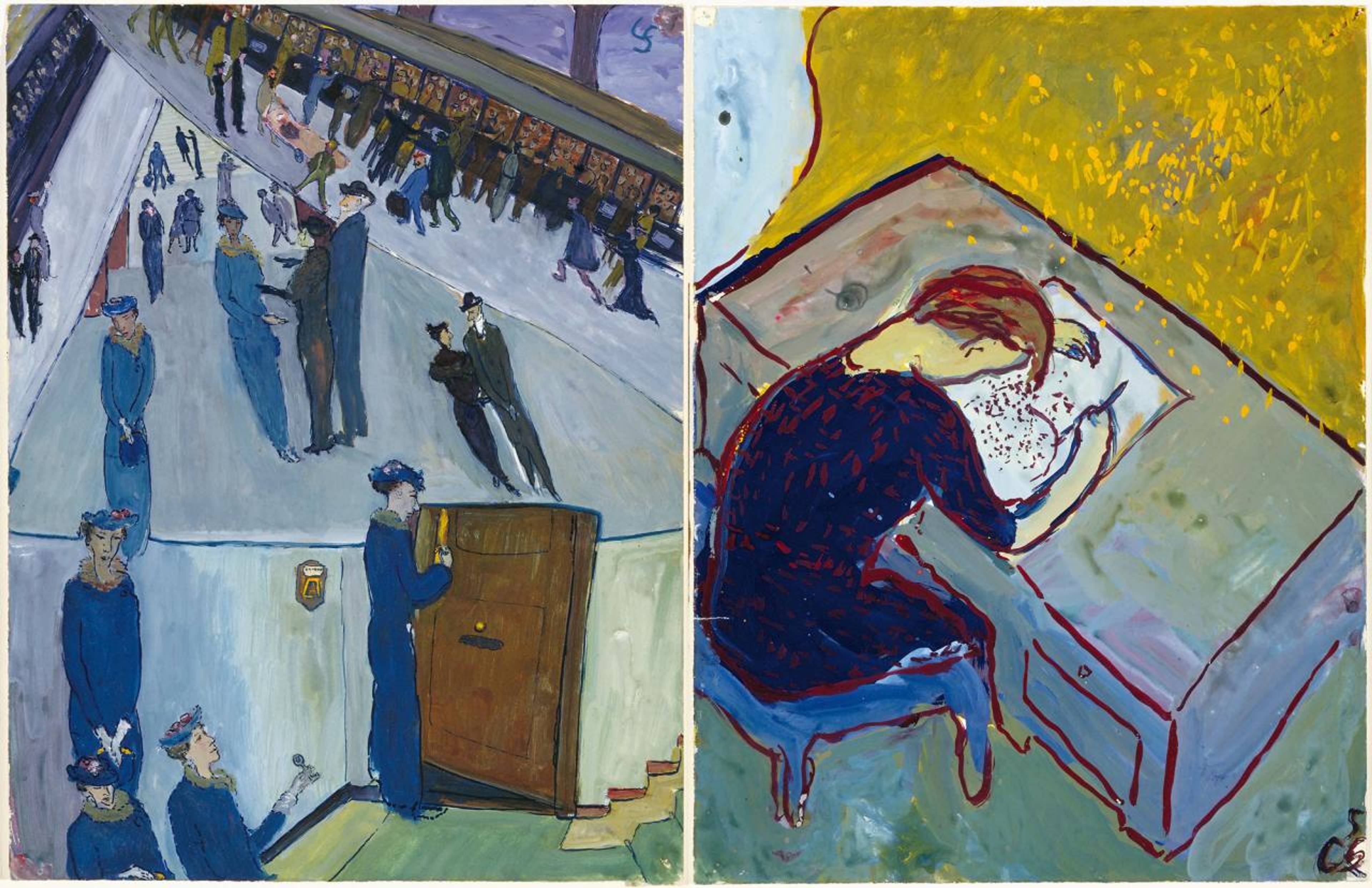

Gouaches from Charlotte Salomon, Leben? Oder Theater?, 1940–42. © Charlotte Salomon Foundation. All images courtesy: Collection of the Jewish Museum, Amsterdam

This is especially evident in the Prelude, where the telling of family stories sets the necessary scene for Charlotte’s. Across several scenes, one especially dramatic event stands out, wherein her mother Franziska’s depression unfolds through different stages of her thinking about death to its final, most tragic consequence – she throws herself out of a window. But there are also moments of utter sweetness, as when Charlotte and her lover lie on a lakeshore in bathing suits, hugging and kissing tenderly. They are framed by a formless, yellowish mass, punctuated by quick, tiny brushstrokes of green, red, and blue – nature of almost Mediterranean warmth dances around them.

Often employed for set-design sketches (for Singspiele), Salomon’s use of gouache might seem didactic. Conventionally, it is the least noble of the painting techniques, befitting the attempts of an early art academy student. But she manages to use it in an experimental way, drawing on its pre-disposition for the speed of execution she needs for the fragile and feverish expression of a non-linear chronology; that is, she recognizes the function of a technique that can only coincide with the fabric of her own story. It is therefore not without ironic assonance that the fictional Charlotte is also a young artist struggling against her rigid art academy professor.

Gouaches from Charlotte Salomon, Leben? Oder Theater?, 1940–42

Salomon takes up the most creative feature of caricature, which is not so much the deformation already widely used by historical avant-gardists like the Cubists and the New Objectivists, but a break with patterns of perspective, which allows her to develop the representation of events in simultaneity or rapid succession. Rather, she draws on the pictorial conventions of more popular forms of expression, such as contemporary photojournalism or cinema. At the same time, one cannot help but recognize Salomon’s ability to mnemonically assimilate the art of the past, especially from the period when the Florentines of the early 15th century were still preoccupied with previous narrative types, while at the same time innovating them with a cinematic dynamism. Salomon looks to Michelangelo and often quotes or reworks the signs of the Sistine Chapel’s vault and its complex modes of representation that constantly deceive the viewer’s gaze, lost between window and frame, narrative lapse and sculptural stasis.

In her gouaches, these windows and frames open rifts into parallel dimensions and interior landscapes. And how shocking is their apparent concretization, predating Arendt’s problematic, of the banality of evil, when Goebbels rejects a project application for a Jewish Kulturbund (cultural association). The Minister of Propaganda is depicted as a common bureaucrat, in profile, his face turned forward, with a flat forehead and receding chin, caricatured into a dumbfounded expression and singing “I’m busy night and day, no time for rest and play.” The lyrical discrepancy between the pettiness of the Nazis and the grotesque brutality of their depiction in Salomon makes her own fate seem – if at all possibly – more prophetic and nonsensical still.

We should not overlook, however, that the main part of the Singspiel is thematically dominated by love, with its impetuous fragility and everyday romanticism, even in one improbable triangle, as the young man we saw lying idyllically alongside Charlotte is also having an affair with her stepmother. This is perhaps the essence of Salomon’s tragicomedy: a sometimes lyrical, sometimes detached portrayal of a life, its affects, its misfortunes. The theater she refers to may be a Chekhovian chamber, where everyone is looking for something that is always slipping through their fingers, trying to escape the horror.

Gouaches from Charlotte Salomon, Leben? Oder Theater?, 1940–42

___

“Leben? Oder Theater?”

Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau, Munich

31 March – 10 Sep 2023