Several conditions have seemingly dovetailed to enable the current and deserved interest in Galli (*1944), who was adjacent to the Neue Wilde painting scene in late-1970s and early-80s Berlin, but isn’t known as part of that predominantly masculine milieu. First, at age 78, she’s an older woman artist, a demographic that commercial galleries are – finally – enamored with. Second, as this show’s handout carefully puts it, Galli “[possesses] a worldview different from that of an able-bodied person,” which coincides with belated efforts to atone for contemporary art’s longstanding ableisms. Third, her scratchily expressive canvases depict human bodies in morphing flux, merging with each other and with nonhuman artifacts, the latter a synthesis with residual heat in art-world discourse – and one that Galli’s work clearly predates. That she is exhibiting with Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, meanwhile, which has not previously been a go-to destination for historical work per se, is evidently due to the gallery’s newly appointed director, the art historian Daniela Brunand, who showed the painter at her recently closed Berlin space, brunand brunand. All of which is to say that Galli, here represented by twelve paintings dating from 1981 to 2014, has one foot in the past and one foot firmly in the present.

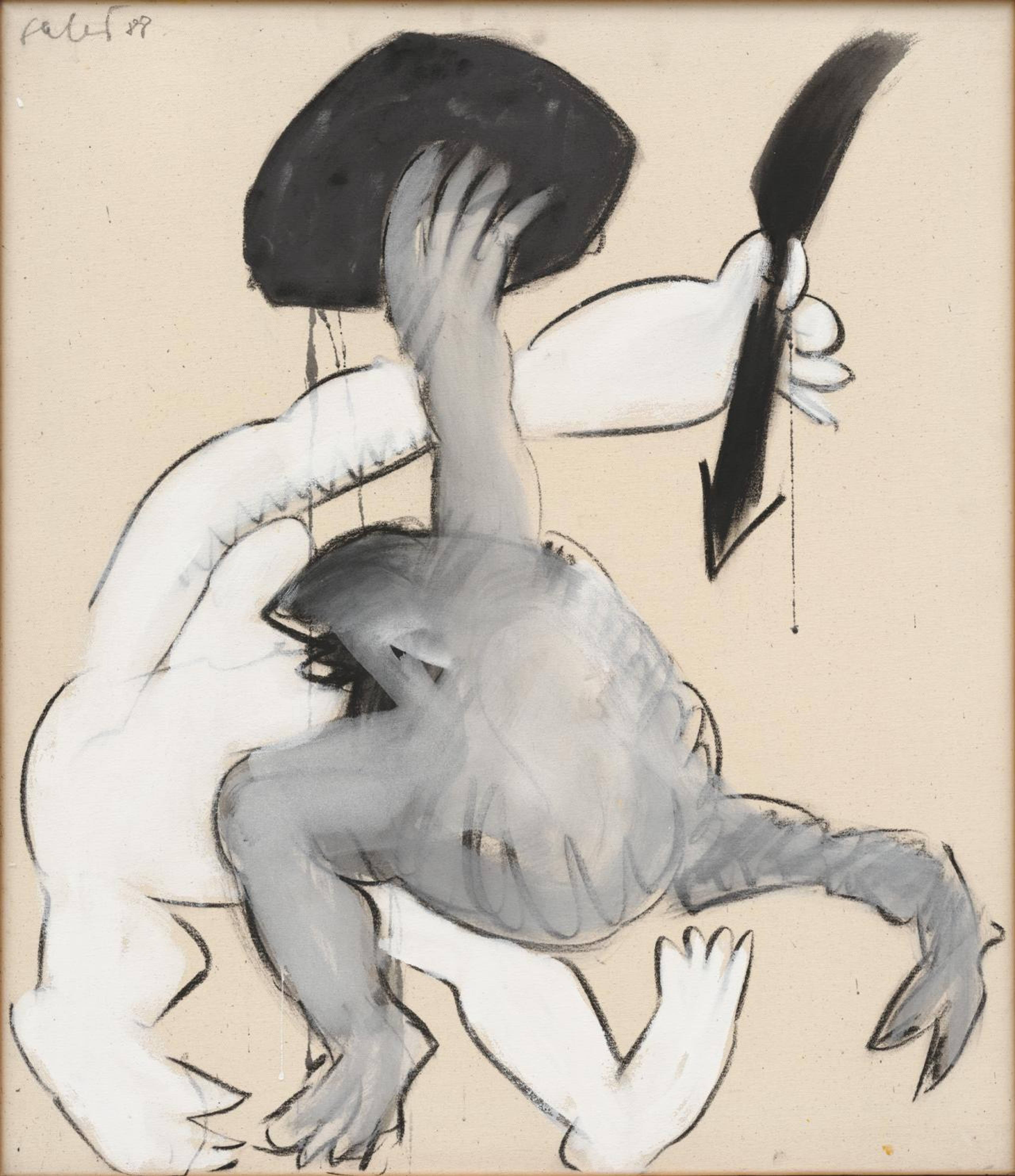

Galli, oft sieht man die Zitrone kaum (Often, One Hardly Sees the Lemon), 1989, acrylic, emulsion and chalk on nettle, 150 x 180 cm

The reality that Galli depicts is expressed through bodies in states of perpetual – if semiabstract – conflict and instability. Against a lemon-yellow background, the mid-action oft sieht man die Zitrone kaum (Often One Hardly Sees the Lemon; 1989) finds two figures in a blunt clinch, one grabbing the other from behind, various limbs distending; a further appendage sprouts from the assaulted one’s face, wielding a club. Galli’s handling is a punky whir of penumbrae, calling to mind the whiplashing, airborne duel in Willem de Kooning’s Pink Angels (1945). In the tightly cropped, semi-cartoonish o.T. (Keilbild) (untitled [Wedge Painting]; 1988), two frog-shaped figures – one grey, the other white – are poised to whack each other with a rock and an arrow, respectively. Further paintings suggest that a mortal adversary isn’t always necessary to make life complicated. noch ein MischiNessi (Another MischiNessi; 1987), which suggests a glyphic study of the body as a prison, finds a black, three-toed leg poking upward out of a dripping rock; the toes, thanks to Galli’s light smudging, seem to waggle forlornly. In Fidschi im Transit (o.P.) (Fiji in Transit [o.P.]; 1984), another single leg conjoins a white hoop, as several limb-like forms either struggle to emerge from or are sucked into its black-abyss center.

Galli, o.T. (Keilbild) (untitled [Wedge Painting]), 1988, emulsion, chalk, and tempera on nettle, 77 x 67 cm

In later paintings, the tone shifts, as Galli seems to find relief in, accord with, or even excitement about extra-human appendages. In the near-weightless, four-panel o.T. (untitled; 2010), the artist pares back her already sparse style to doodle on white in black acrylic lines. Antic mutations emerge left and right: a chair sprouts arms and legs (though not a head) and prepares to eat off a plate; one arm growing from a house is about to draw something on a rectangular support, while another reaches from one panel to the next, where it’s clasped by a semi-human figure. The whole has the unfettered, naturally reality-bending quality of children’s drawings. As much as one can describe these human-nonhuman interfaces in McLuhanite, cyborgian, or animist terms, they show Galli working out of a condition of sustained, ambiguous plasticity that’s suggestive of continuous possibility, a combination of registers reflected in the show’s title: “Whoever can count to three can be saved.”

Galli, Fidschi im Transit (o.P.) (Fiji in Transit [o.P.]), 1984, chalk and tempera on nettle, 125 x 100 cm

Read clockwise, the show ends with Galli’s newest painting, the chalky little tempera o.T. (untitled; 2013–14), which is exemplary of how the scale of Galli’s work has shrunk as she’s gotten older. The canvas is nearly filled by a blue-grey machinic device with a small, boxy upper section, fronted with a grille, that suggests an undersized head; it’s angled slightly backwards, as though twisting its neck in intense pain. It has a single hand, the fingers warped and splayed across its featureless frontage; from the lower edge of the canvas, another, darker hand reaches up as if in consolation. For a body of work that, in its earlier phases, traversed fight after fight seemingly occasioned by difference, it’s a near-redemptive, strikingly empathetic, and determinedly open-ended vision of support for suffering others, whoever or whatever they may be.

Galli, o.T. (Untitled), 2013/14, emulsion and tempera on canvas, 70 x 60 cm

___

“wer bis drei zählen kann, kann gerettet werden”

Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin

5 Nov 22–11 Feb 23