In her book Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (2015), scholar Simone Browne cites an 18th-century New York City law that “mandated enslaved people carry lit candles as they moved about the city after dark.” From the country’s very beginnings, at least, race in America has been inextricably tangled with visibility. If so, how does one vie, against odds, to be seen? And when is it more strategic to vanish out of sight entirely? Curated by Ashley James, “Going Dark” asks some of these questions through its presentation of 114 artworks by twenty-eight artists – most of them Black, many of them American. The show traces its themes along a historical arc from the 1960s through today, with work by veterans like Faith Ringgold and David Hammons and by younger artists like Sondra Perry and American Artist. In all the works, the figure is obscured, implied, blurred, or even enshrouded in penumbral hues: positioned, in the words of a wall text, “at the edge of visibility.”

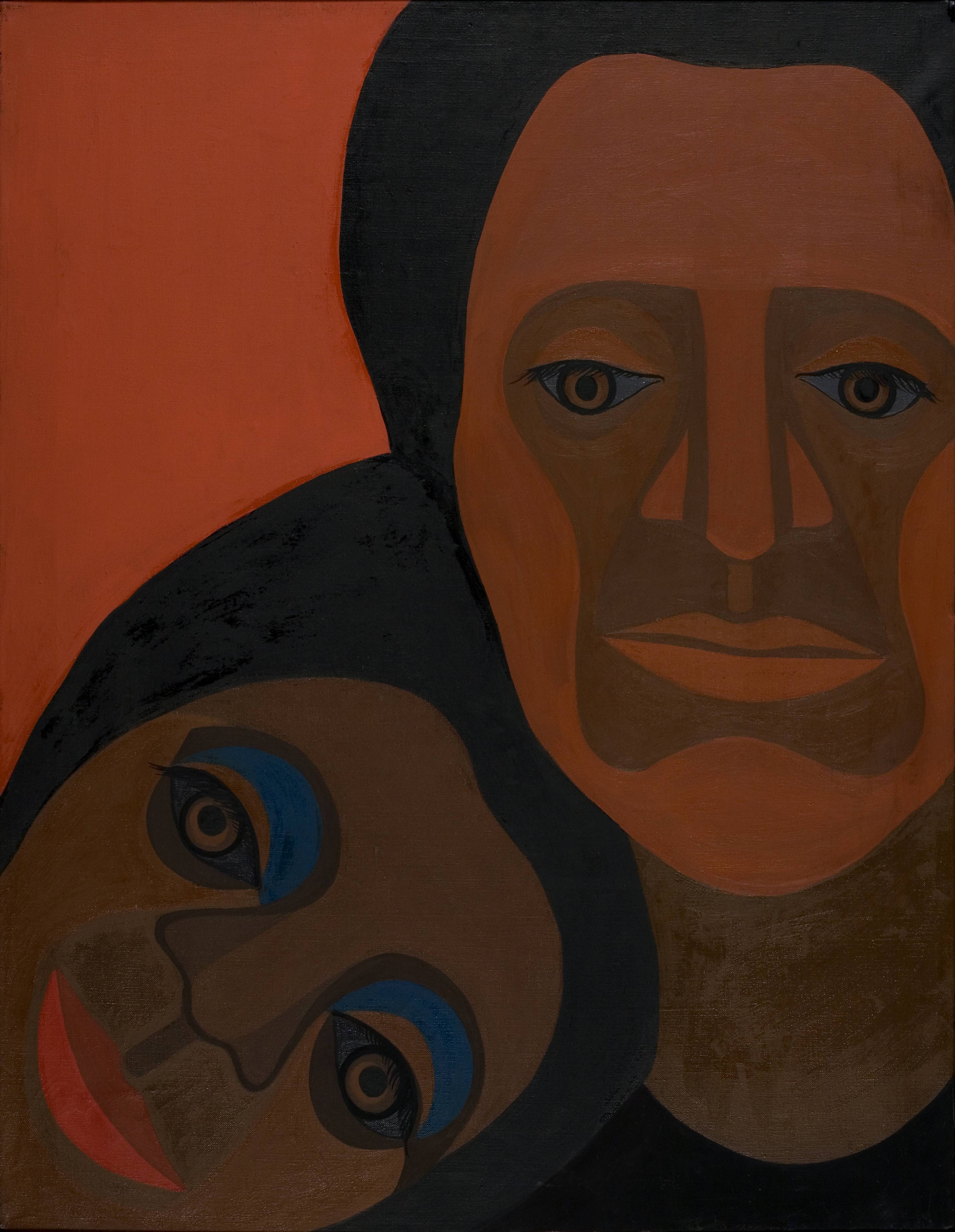

Faith Ringgold, Black Light Series #4: Mommy and Daddy, 1969, oil on canvas, 76.2 × 61.3 cm. © 2023 Faith Ringgold/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy: ACA Galleries, New York.

Farah Al Qasimi, It’s Not Easy Being Seen 2, 2016, inkjet print, 120 × 96 cm. Courtesy: the artist and François Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles

John Edmonds, Untitled (Hood 13), 2018, inkjet print, 127 × 83.8 cm. © John Edmonds. Courtesy: John Edmonds Studio

Lorna Simpson, Double Negative, 1990–2022, gelatin silver print, 114.3 × 91.4 cm. © Lorna Simpson. Courtesy: the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: James Wang

That means many things. To make Slow Fade to Black II (2009–10), for example, Carrie Mae Weems blurred famous photos of Eartha Kitt, Leontyne Price, and other Black luminaries. Is her gesture meant to fend off the societal impulse to see these women as icons instead of as people? Or does it allude to the broader erasure of these women from cultural histories? The Black protagonist of Kerry James Marshall’s well-known painting Invisible Man (1986), meanwhile, is rendered chromatically indistinguishable from the background, save his eyes and smile. It’s one of many instances when the show, heavy with histories of painterly abstraction, reconfigures the monochrome as a place to lurk and vanish – and sets its traditions in direct dialogue with the flatness inherent to systems of identity built around skin tone alone. Sondra Perry’s work spotlights big tech’s penchant for deeming things “anomalous” – and, therefore, invisible. In Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016), her digital avatar robotically informs viewers that she bears little resemblance to the actual artist, averring: “Sondra’s body type was not an accessible pre-existing template.”

If some of these pieces and themes already sound familiar – Perry’s workstations, for instance, have appeared at MoMA, The Kitchen, ICA Boston, and the Serpentine Galleries in recent years – I took it as a sign that James, her scholarly achievements well proven, is unafraid to meet people and institutions where they are. Not all visitors will have seen Perry’s work four times, nor are all institutions up to speed – to put it bluntly – when it comes exhibiting artists of color. Responding to a 2020 complaint from employees, the Guggenheim formed a committee to examine why, among other issues, “the museum has never held a solo exhibition of a Black artist.” Still, it was surprising to learn that “Going Dark” marks the first time the museum has shown Ringgold, Dawoud Bey, and Chris Ofili.

View of “Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility,” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2023. Courtesy: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

The latter’s Blue Bathers (2014) is a joy, its subtle shades of deep blue barely revealing striations, butterfly patterns, and harlequin checks that surround what seems to be a huddled figure. It is one of many works here that are nearly un-photographable, apparently as part of James’s ingenious decision to make our smartphones, in some sense, a secondary subject of the show. Labels beside two retro-reflective vinyl prints by Hank Willis Thomas – Pledge and One Million Second Chances (The Invisible Men) (both 2018) – urge viewers to photograph each work with flash. Doing so reveals figures, respectively gathered in scenes of protest and official ceremony, who otherwise appear like faint ghosts to the naked eye. The site-specific commission by American Artist (Security Theater, 2023) demands even more of our relationship to our phones: To enter alcove halfway up the Guggenheim’s rotunda, visitors must leave their devices in a locked pouch that can only be reopened on the ground floor. Together, these artworks offer a reminder that the phone is more than just a tool for mindlessly transmuting one’s gallery visits into bland Instagram posts. To many, a smartphone on the scene can raise the stakes – whether because it abets systems of surveillance, or allows abuses of power to be documented in real time.

It is to James’s credit that the show extends questions about visibility well beyond its artworks – to our camera phones, so poorly equipped to reproduce shadowy hues, as well as to audio guides, which elsewhere are so often appended as afterthoughts in lip service to accessibility. Here, they’re mentioned in the main wall text and loaded with exercises in “slow looking.” Even the Guggenheim’s spectacular architecture is brought into focus. Those who part with their devices to experience Security Theater are ushered into a small viewing room, where a gentle shock awaits. There, live security footage of the rotunda reveals AI identifying the bodies of visitors strolling along the spiral ramp as “humans.” It is Frank Lloyd Wright’s gem made into a panopticon of cartoonish extremes, where no one can go incognito.

Dawoud Bey, Untitled #25 (Lake Erie and Sky), 2017, gelatin silver print, 111.8 × 139.7 cm. © Dawoud Bey. Photo: Sean Kelly

Sondra Perry, Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation, 2016, digital color, video, sound, 9:05 min; and bicycle workstation, 172.7 × 106.7 × 40.6 cm. © Sondra Perry. Courtesy: the artist and Bridget Donahue, New York

___

“Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility”

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

20 Oct 23 – 7 Apr 24