“The Yellow Heart gives you the opportunity to abandon the real environment for a certain time, to visit a space in strong contrast to the natural environment, and to relax yourself,” a male voice narrates in Gelbes Herz (Yellow Heart, 1968), a captivating video by Haus-Rucker-Co (1968–92). It depicts a young and handsome couple entering a pneumatic sculpture by climbing some stairs, taking off the plastic helmets they wore outdoors, and zipping closed the plastic surface, the whole scene underpinned enticingly – at least retroactively – by the hippieish electric guitar of Iron Butterfly.

I could go on writing endlessly about just this one work, for it brings together several topics so central to Haus-Rucker-Co’s time, and with such enduring resonance. On the one hand, early works like Yellow Heart are generally read as critical commentaries on urban society’s increasing alienation from nature and the destruction of the environment. On the other, the undisrupted optimism of these technoid fantasies regarding an awakening leisure society, here literally embedded in a love machine, lend such works less to critical reading than to playful exercises in possible futures.

View of “Atemzonen”

View of “Atemzonen”

The exhibition “Atemzonen”(Breathing Zones) marks a rare opportunity to see some original works by the experimental art and architecture group. Its materials, comprising original drawings, record covers, project sketches, collages, documentary photographs, and some Pop Art-ish objects from the archive of group co-founder Günter Zamp Kelp, are arranged at Lentos in six chapters, foremost in glass vitrines separated by printed textile flags. Among other artifacts are Roomscraper (1969), a raised finger silkscreened on an inflatable stele, and the hot-pink transparent jumpsuit Electric Skin (1968). Conceived as either consciousness-expanding or body-sensitizing machines, these wearables and often phallic furniture objects have been musealized here in displays beyond the reach of our use.

The focus of the exhibition is on the“making of” Haus-Rucker-Co’s most famous projects, among them the sketches for Pneumacosm (1967), a pneumatic living unit that could be plugged into a vertical megacity, and Rooftop Garden ( 1971), which envisioned blimp-like ecospheres atop New York City high-rises. One of the group’s most spectacular endeavors, the 1971 exhibition “COVER: Surviving in a Polluted Environment” at Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, dealt similarly in the rehabilitative possibilities of enclosure, prompted by increasing air contamination. The Mies van der Rohe villa was completely wrapped in PVC, an exterior technical achievement coupled with the synthesis of a kind of nature preserve inside, where springtime temperatures warned of the dangers of pollution.

Balloon for 2, 1967

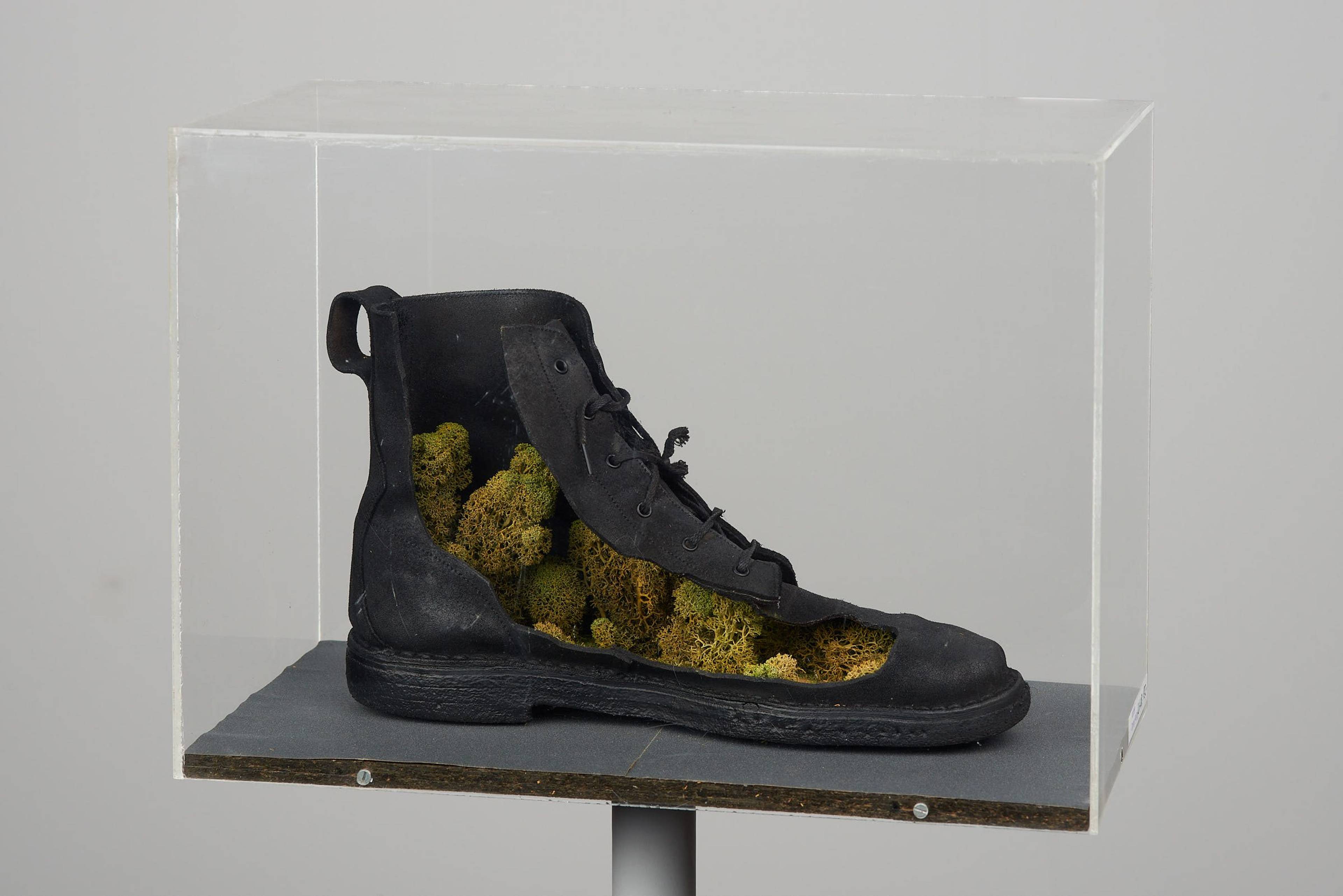

Laurids Ortner, Piece of nature for your foot, 1972

Commenting on that exhibition in Krefeld, a contemporaneous article in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung inveighed against the group’s overly didactic tendencies, focused on Haus-Rucker-Co’s somewhat “obtrusive” moralism on environmental protection. Similar criticism might be directed towards the current exhibition at Lentos, as one gets the impression that the chapter themes were overfit to our own zeitgeist’s sustainability interests, as much as the concerns of Haus-Rucker-Co’s own time. Moreover, the focus on environmentalism misses an opportunity to further contextualize the group’s work, such as questions of preserving Brutalist architectures or cityscape planning, while a bolder, more experimental design might have lent the atmosphere vibrancy, even granting that “Breathing Zones” is an archive exhibition, not a project show.

From its founding in 1967, Haus-Rucker-Co – initially Zamp Kelp, Laurids Ortner, and Klaus Pinter, later joined by Manfred Ortner and, during their short episode in New York, Caroll Michels – was a collaboration in envisioning playful utopias. Though the pun of Haus rücken (to move buildings) was a deliberately provincial allusion – the Hausruck being a chain of hills in the Upper Austrian countryside – they made a remarkable international career, as well as an intriguing impact on the art world. Not only were their projects shown in many art institutions, including documenta 5, Kunsthalle Wien, the Walker Art Center, and, more recently, Berlin’s Haus am Waldsee and Kunsthal Rotterdam; they also enjoyed a solo presentation at the Gallery Rudolf Zwirner in Cologne as early as in 1969. Its members eventually split in 1992 to concentrate on their independent practices: The Ortners went on with their highly successful firm, O&O Baukunst, while Zamp Kelp pursued a solo career as an architect and an artist.

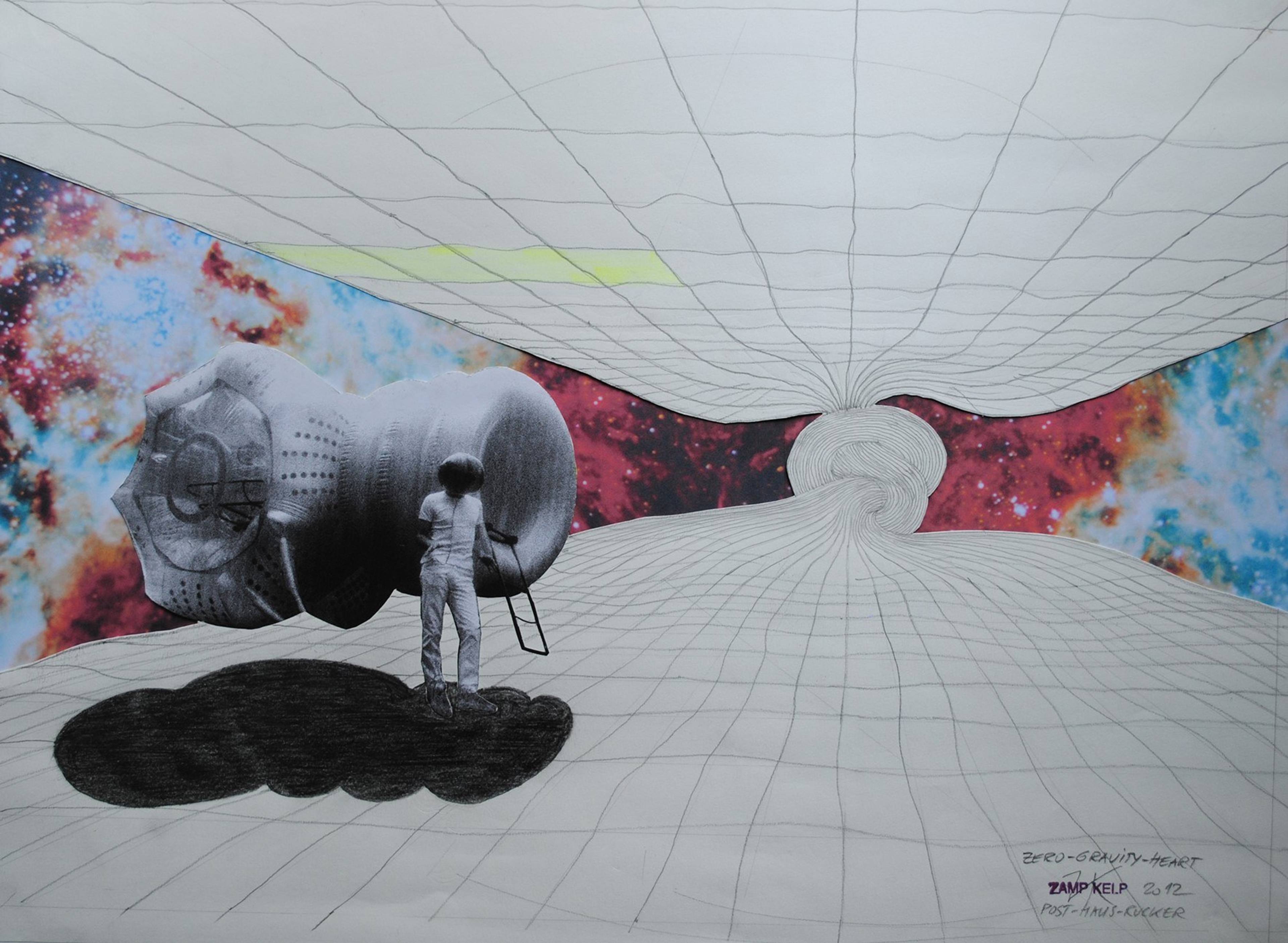

Günter Zamp Kelp, Yellow Heart / Zero Gravity Heart, 2012

Haus-Rucker-Co’s striking signature lay in fact in their penchant for grand architectural gestures. The leap from small to gigantic was intrinsic to blowing up plastic inflatables to large-scale monuments, no less in their efforts to devise fascinating solutions to problems never before raised. Their impetus was above all a shared opposition to the overall dark horizon of late functionalism, which made itself felt in the monotony of the suburbs and the exploitation of the planet as no more than a trove of natural resources. Perhaps our own gloomy present needs exactly a few poetic urban fantasies that can open up glimpses of a more cheerful future.

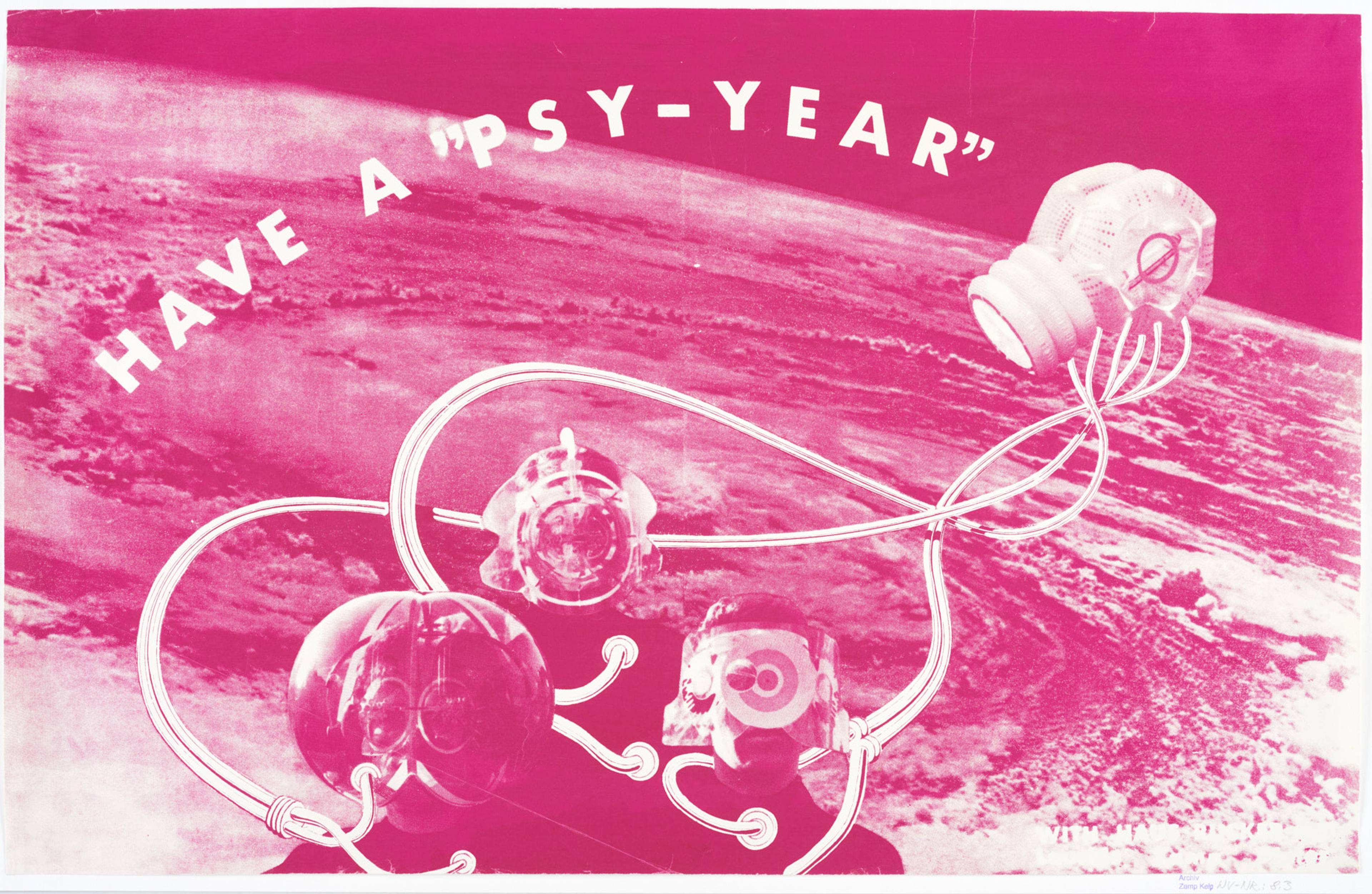

Vanilla Future, Have a Psy Year, 1968

___

“Atemzonen” (Breathing Zones)

Lentos Museum, Linz

6 Oct 2023 – 25 Feb 2024