A museum exhibition is a triumphant affair for the marquee artist – an occasion to reflect on their achievements and importance. It’s unheard of for a museum to put up works in order to take down their author. Why devote so many resources to acquiring (or borrowing) and hanging art just to tell the public it’s bad? Leave that to the press!

“It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby,” organized by the Brooklyn Museum’s Sackler Center for Feminist Art, has caused a stir because it violates this ecosystem of celebration and critique. Of the dozens of exhibitions this year that mark the anniversary of Picasso’s death, this is the only one that surveys the feminist art of the half-century since and, expanding on Gadsby’s 2018 comedy special Nanette, contextualizes Picasso’s life and work with both his personal misogyny and the institutionalized misogyny that assured his canonization.

View of “It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby,” Brooklyn Museum, New York, 2023. Courtesy: Brooklyn Museum

Kaleta Doolin, Improved Janson: A Woman on Every Page #2, 2017, paper, ink and textile, 30 x 23.5 x 5 cm. © Kaleta Doolin. Courtesy: Brooklyn Museum

For all its seeming novelty, the exhibition’s critical approach extends the current museological trend of institutions using wall texts to unpack the patriarchal, white-supremacist biases of their permanent collections; the galleries of American art upstairs from “It’s Pablo-matic,” for instance, narrate the romanticization of Western expansion and the erasure of Indigenous civilizations in 19th-cenutry landscape painting. Such interventions are performed by museum professionals. “It’s Pablo-matic” is different not only because it happens in a temporary exhibition and directs the critique at a single artist, but because it highlights Gadsby’s status as a non-expert. A Cubist study the comedian painted at seventeen hangs near the entrance; in the label, Gadsby delights in the prank of putting such juvenilia in a museum. Gadsby’s amateurish commentary – pointing out the “anuses” Picasso drew on women’s chins and foreheads, etc. – is juxtaposed with conventional art-historical descriptions provided by the museum’s staff curators.

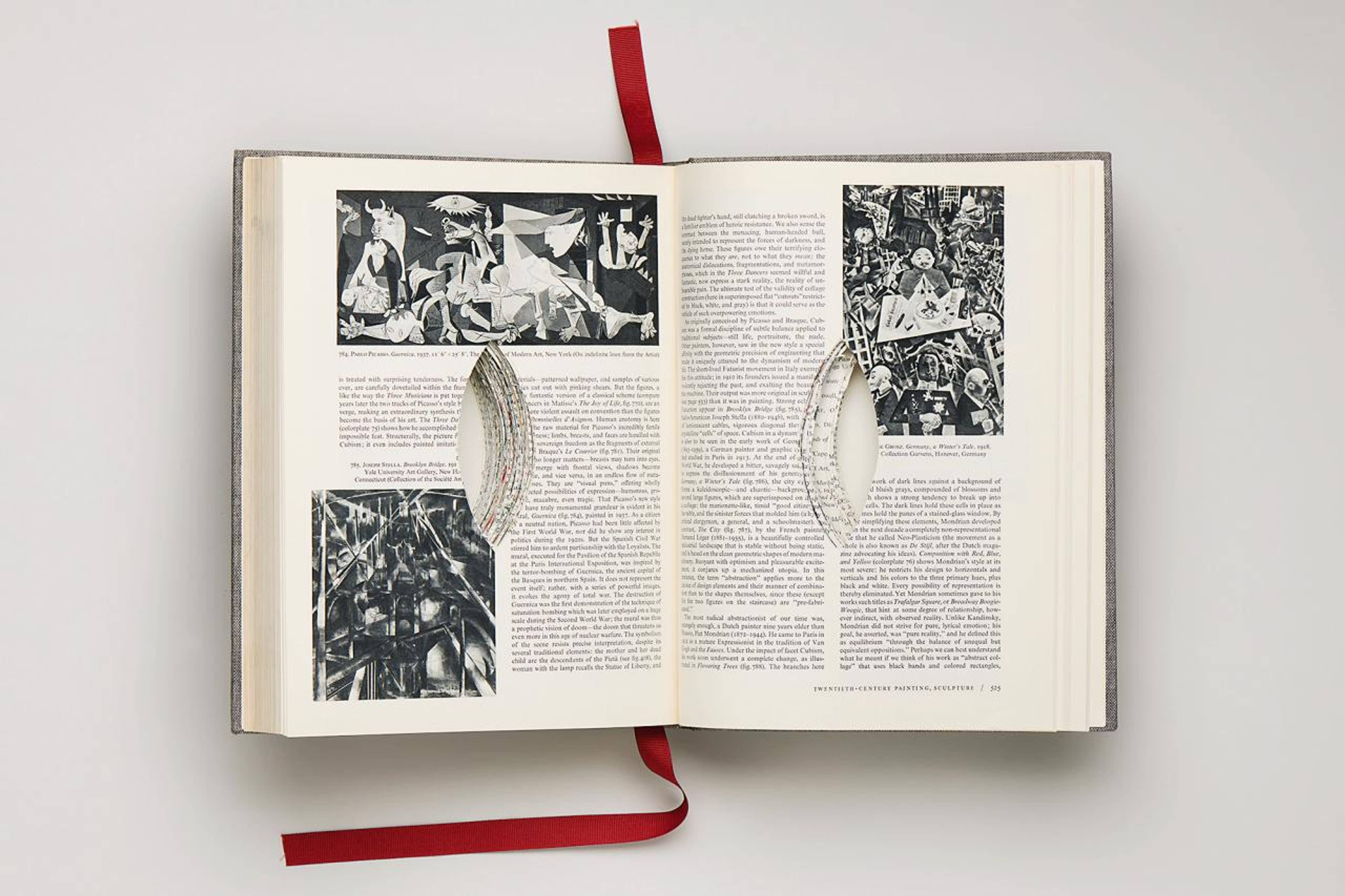

At the same time, the show locates Gadsby’s Picasso routine in a tradition of feminists taking on the art world’s patriarchy with humor, from mordant commentary to dick jokes. In the first gallery, Picasso’s Le Sculpteur (The Sculptor, 1931) – where seven phalluses play hide-and-seek among curving, overlapping shapes – is swarmed by Guerilla Girls posters. The opposite wall is tiled with a photo diptych devised by art historian Linda Nochlin; she had a picture taken of a nude man holding a tray of bananas just below his penis, and put it beside a 19th-century image of a comely lass carrying a tray of apples at breast level. Nearby is Improved Janson: A Woman on Every Page (2018), in which Kaleta Doolin cut a vaginal incision through H.W. Janson’s History of Art (1962), a classic textbook that Gadsby studied as an unsuccessful art history major.

Critics aren’t Alex Greenberger and Jason Farago aren’t threatened by feminism, but by a cultural paradigm that makes criticism irrelevant.

In Nanette, Gadsby says Cubism is valuable because it shows “all the perspectives,” with a caveat: “Any of those perspectives a woman’s? No?” The survey of feminist art accompanying the Picassos provides those perspectives, some at odds with Gadsby’s. There’s a lot of sex positivity in the third gallery that doesn’t square with the comedian’s second-wave feminism. In Hannah Wilke Through the Large Glass (1976), the eponymous artist poses in mannish attire – a porkpie hat, a vest, pants – behind the cracked, transparent plane of Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23), and performs a slow, coy striptease. Betty Tompkins’s Fuck Painting #6 (1973) is a blown-up segment of her husband’s contraband porn stash, a raw image of a dick entering a woman from behind. These artists were once ostracized by their feminist peers for their frank expressions of sexuality, but Gadsby shies away from commenting on that. In the audio guide entry for Fuck Painting #6, they say: “I see a vase – what do you see?” All perspectives are valid, but Gadsby’s squeezes out the others.

Guerrilla Girls, Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get into the Met. Museum?, 1989, offset lithograph, 28 x 71 cm). © Guerrilla Girls. Courtesy: Brooklyn Museum

Early reviews of “It’s Pablo-matic” were not kind. In Artnews, Alex Greenberger complained about the show’s “disregard for art history.” In the New York Times, Jason Farago said the Picassos included aren’t even that good. But this is New York City; a viewer who wants to see standard-account great Picassos can go to MoMA. The curators’ response on Instagram – “… that feeling when IT’S PABLO-MATIC gets (male) art critics’ knickers in a twist: sorry not sorry” – was equally ridiculous. The critics aren’t threatened by feminism, but by a cultural paradigm that makes criticism irrelevant.

While “It’s Pablo-matic” never intended to tell art professionals things about Picasso and feminism we didn’t already know, it is a weird, unprecedented twist in the way museums are shifting art-historical narratives. Gadsby’s contribution is best understood as an exercise in institutional critique – a goofy Andrea Fraser who came in and turned everything upside down. The problem, as the critics woefully note, is that these ideas have already been digested in popular culture. In the clips from Nanette playing in the penultimate gallery, a silver Netflix hovers over the comedian like a guardian angel. What would it look for a museum to elevate the voices of non-experts who are also non-celebrities? How can a museum truly be open to all perspectives?

Dara Birnbaum, Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman, 1978–79, single-channel video, color, sound: 5:30 min. © Dara Birnbaum. Courtesy: Brooklyn Museum

___

“It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby”

The Brooklyn Museum, New York

2 June – 24 Sep 2023