Let’s assume you’ve watched her porn and looked at her portraits by Nobuyoshi Araki. You’ve downloaded Endless Waltz (1995), director Koji Wakamatsu’s smutty, juvenile, charming dramatization of her suicide and relationship with the jazz saxophonist Kaoru Abe (in that order, oddly). You’ve even read a French translation of the Mayumi Inaba novel that Wakamatsu based his film on, the one that caused her orphaned sixteen-year-old daughter to sue Inaba for invasion of privacy.

Let’s say you’ve already done these things, so there’s no need to talk about them. What I mean is that the life of the avant-garde writer Izumi Suzuki (1949–86) is a distraction too massive and glamorous to be omitted – though that’s what I intend to do. I’m leaving out her biography because I want to talk about her work, and ultimately about a different Suzuki. Someone no one knew, whose only voice was her writing. I don’t know much about her, only that I believe she was very lonely.

Stills from Kōji Wakamatsu, Endless Waltz, 1995

Suzuki used simple, even crude tools to shed light on the less accessible corners of the heart: alien invasions and time warps, but also gossip, domestic disputes, and (yes) sex. Her work examines the cruelty and sometimes the intimacy of modern life: Why should we care about other people? Do they really care about us? What does it mean to be an interesting person? What about an uninteresting one? She’s a master of mundane dialogue (two friends talk about their cosmetic routines, etc.), fragments of ordinary life as lived by nominally unremarkable people – groupies, office workers, dropouts – that suddenly offer vertiginous perspectives on human existence. Take this humdrum scene from the story “Hey, It’s A Love Psychedelic!” in which time has become discontinuous. Reyco is one of the few who senses what is happening:

As Reyco adjusted the heat in the shower, she vaguely wondered what the future held for her. Eighteen. Stranded between high school and college. Am I gonna squeak into some third-tier school and end up working in an office? Or am I gonna answer phones at some record company? Pretty sure it’ll be one or the other. I know my own future.

The reader is pitched between the grand and terrifying prospect of rifts in time and the quotidian bleakness of a life whose future holds neither promise nor uncertainty. Suzuki wants us to understand both, and the way they are united in our experience: the human capacity for wonder and the human propensity to disappoint.

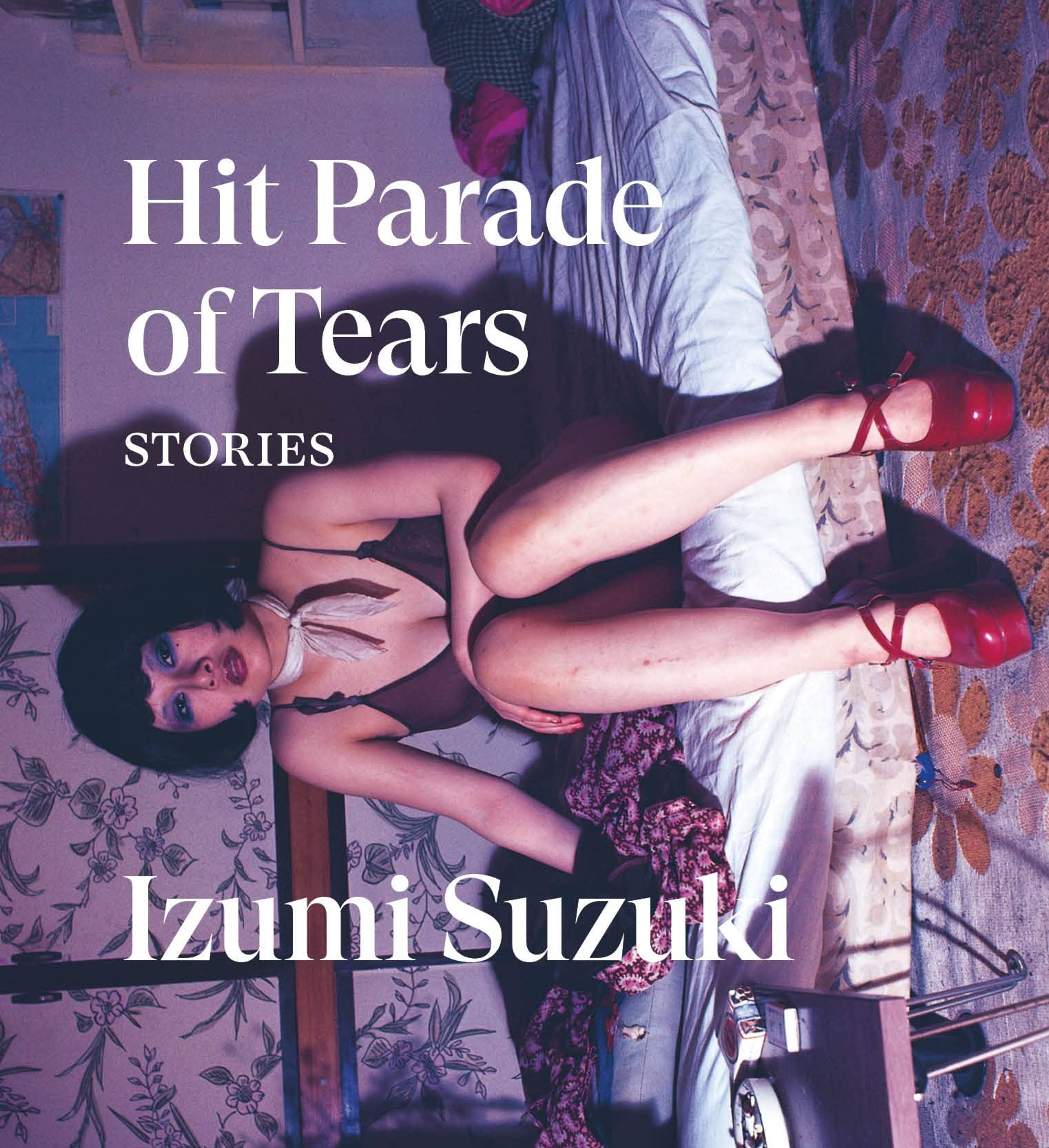

Portraits of Izumi Suzuki. Photos: Nobuyoshi Araki

Suzuki’s style is spare and often abrupt. Occasionally, like a flick of the wrist, her prose turns lush, perhaps just to show us that she can: “The hard sky glitters a deep, uniform blue.” Her work is so reliant on dialogue as to be fragmentary, even collage-like. Our understanding of the world in which the story operates is built on casual overheard conversations, sometimes seemingly random ones, filled with textures of daily life. In a story about a group of people who live extraordinarily long lives, a scene introduces us to the unromantic contours of a marriage:

“Have we got any pills? Any ludes or soma? Anything?”

“No.”

“Don’t waste your words, do you? The pink ones will do. I’d even take some bromisoval.”

“It’s hard to get hold of that stuff now,” she said calmly. “I can always go buy some solvent.”

The world appears to us in voices, and those voices often create a darker, more disturbing image than the story’s conceit alone might suggest. A story about living to the age of 180 sounds different from a conversation between two 180-year-olds whose lives are so degraded they will do anything to get high. Suzuki’s stories are sometimes humorless and sometimes very funny. I screamed with laughter at the ending of the first story in Hit Parade of Tears (2023), her new English-language collection, about a woman who bears the spawn of a sexually prodigious alien: “What will I do if he gets all the girls at kindergarten pregnant? Would you believe me if I told you that this keeps me up at night?” The way this tacky, obscene, wildly imaginative question is folded into a relatable concern – what mother doesn’t worry about how her child behaves in kindergarten? – is only improved when Suzuki tips her hand with “Would you believe me…” She knows how outrageous it is, and she doesn’t care. Outrageous is one version of the magic of creation.

Suzuki’s worlds are basically reality as we know it with a thought experiment thrown in: What if the protagonist fucked an alien? What if she was an alien? What if she was the only one who realized time was broken?

Reviews of Suzuki’s first collection translated in English, Terminal Boredom (2021), were understandably heavy on biographical detail – the porn and the portraits and the Wakamatsu film – and tended to emphasize Suzuki as a female figure in a sci-fi world dominated by male writers. This narrative fits conveniently with an emphasis on gender relations in her stories. It’s also absolutely correct: She devotes a lot of energy in her texts to exploring many different and sometimes contradictory concepts of femininity and masculinity.

Yet, I don’t believe that Izumi Suzuki sat at her desk writing story after story in order to tell us about men and women. That’s not the beating heart of the thing. Loneliness, rather, was her subject. The maddening loneliness of being an outcast who is intelligent enough to see society clearly. The grief of loneliness and what it says about the desire for love in a society that is atomized and transactional. Or the inability to want love. This is her work’s obsession. The protagonists of her stories are often utterly, improbably, or even impossibly alone. Women trapped in mental hospitals or horrible marriages, or women in seemingly normal social situations who nonetheless feel no connection to those around them. Just as any writer leads their characters through an arc of emotional development over the course of a story, Suzuki’s characters cultivate a range of emotional failures – it is and isn’t development – that accompany isolation: callousness, numbness, shallowness, exhaustion, though these characters might long for something different. Take this exemplary passage in “The Covenant”:

“I’m nothing special. But who cares? I’ve got a goal in life.”

“What is it?”

“Maybe something you can relate to. See, sometimes I wonder if I’m really a human being at all. But I think it’s just that I’ve lost something. I don’t feel anything. I can’t empathize with anyone. So, I’m thinking about falling in love. If I could feel all that jealousy and pain and whatever else comes with it, maybe I could get my human emotions back.”

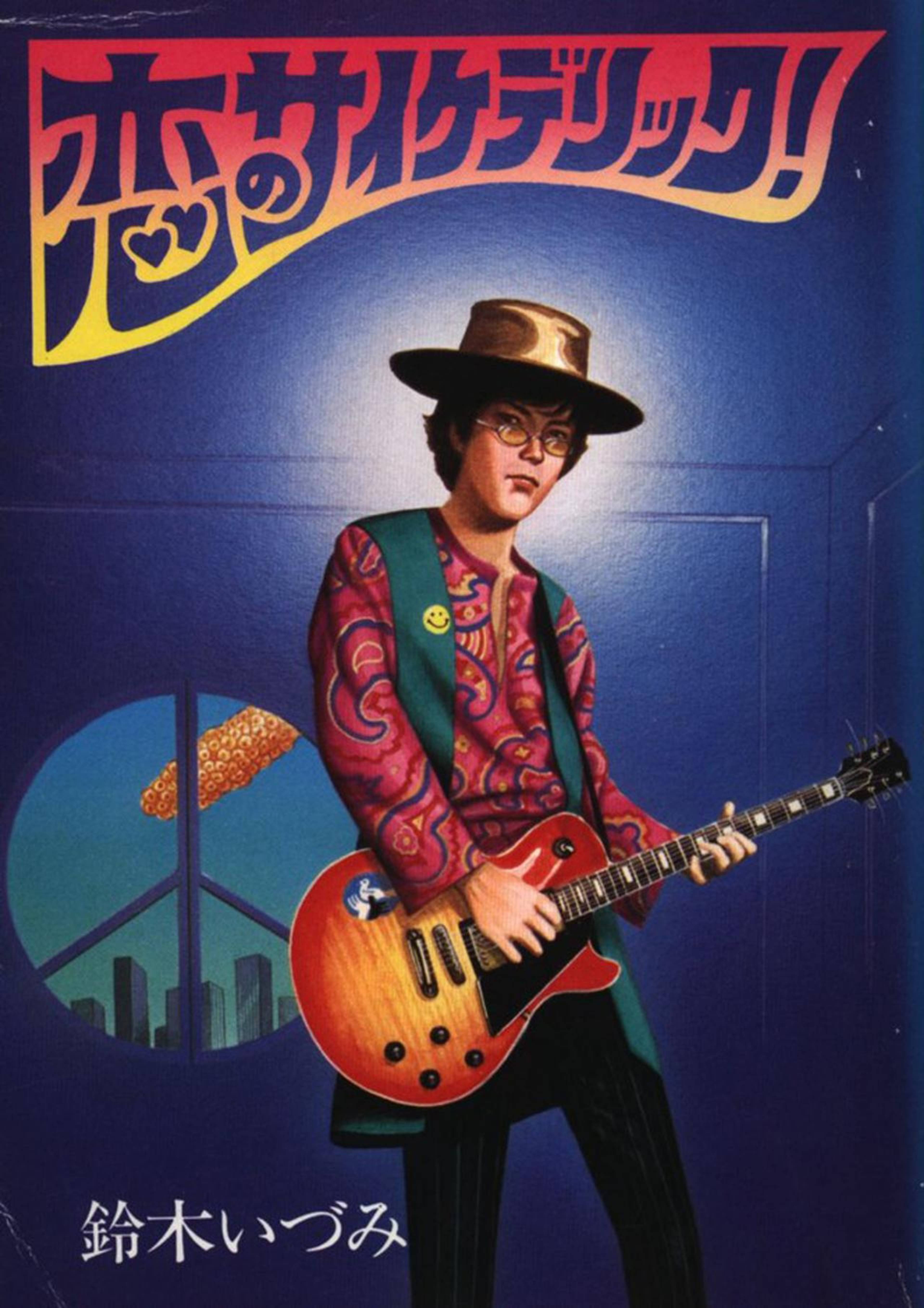

Izumi Suzuki, A World of Women and Women (女と女の世の中), 1978. Courtesy: Hayakawa Publishing, Tokyo

There is a certain school of writing – let’s call it the well-adjusted one – that says the test of a book for a writer is if it makes a space in which, quite naturally, she can say what she wants to say. Then there is the obsessive school, in which the author is never done with what she wants to say, because the thing is, in some sense, unspeakable. The book is an arena for approaching again and again the maddening, opaque surfaces of life, the seemingly unsayable things that present themselves like personal insults. For Suzuki, it is the experience of isolation. What it does to a person, how they feel about it. There is a defiance in the way her characters proclaim their loneliness, often as the defining aspect of their identity. It’s something that people are typically ashamed of.

Her concern with the human (anti-)social experience is so deep that I would go so far as to call her sci-fi label incidental. Suzuki herself once said she published in sci-fi magazines simply because those were the outlets that would pay for her work. Her writing is sometimes compared to that of Philip K. Dick because of a shared counter-cultural vibe, but it’s a weak comparison. Except for her famous story “Women and Women” (1977), about a world inhabited almost entirely by – you guessed it – women, Suzuki generally does little of the sci-fi practice known as “world building.” In its worst form, this is an energy-intensive activity that absorbs otherwise useful creative oxygen and messes with the pacing: and that’s how we discovered the method to cultivate the high-nutrient cyanobacteria on Mars , and so on. World-making is the genius of any Philip K. Dick work, in which every detail reveals another vista in a twisted emotional landscape. To be basic about it: It’s so touching and messed up that Rick goes through the motions of caring for his electric sheep to save face in front of his neighbors.

Suzuki’s worlds, by contrast, are basically reality as we know it with a thought experiment thrown in: What if the protagonist fucked an alien? What if she was an alien? What if she was the only one who realized time was broken? Suzuki’s worlds aren’t devastating because the sheep is electric; they’re devastating because the people closest to you actually hate you, because you’re married to a philandering drunkard, because your closest friend is a murderer and you probably get along so well because there’s something very wrong with you.

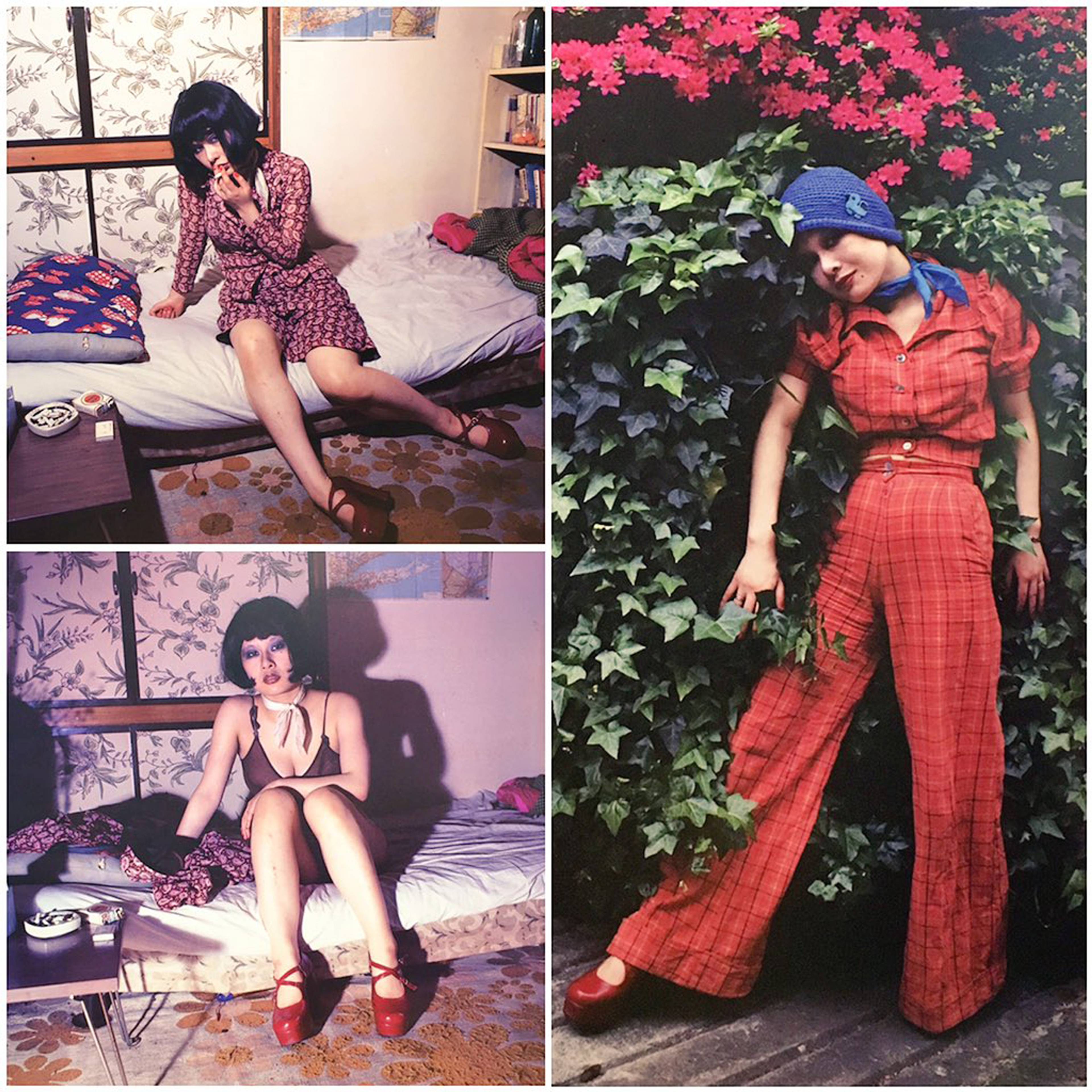

Izumi Suzuki, Love’s Psychedelic (恋のサイケデリック), 1982. Courtesy: Hayakawa Publishing, Tokyo

In fact, Suzuki’s stories are full of recognizable references to mainstream and experimental music, film, and novels from Japan and the West. That is, they take place in a highly realistic, mid-century Japan, not an imaginary world that is foreign because it is science fiction. TV is a powerful presence, as are ad slogans and snatches of songs: “So powerful! So vulgar! So sublime! So incredible!” goes one bit of television audio.

Of course, elements of science fiction do appear in Suzuki’s work – they are considered its identifying feature – but they also operate according to an emotional logic. Often, the lonely protagonist is the only being to experience or understand a paranormal phenomenon (or at least is isolated from anyone who shares their experience). They alone meet the alien, learn sorcery, discover their own capacity for telepathy, and so on, and their supernatural experience encapsulates the loneliness of being exceptional, aware, or a little crazy – usually all of those things. Do alien and alienated share an etymology in Japanese?

The stories in Hit Parade of Tears are rebellious tragedies. A unique fate visits the misfit, ensuring that they will never truly be understood. But of course, a book is an attempt to understand, to make understandable. In her contributions to the obsessive school, Suzuki attempted to make the alien and the alienated legible.

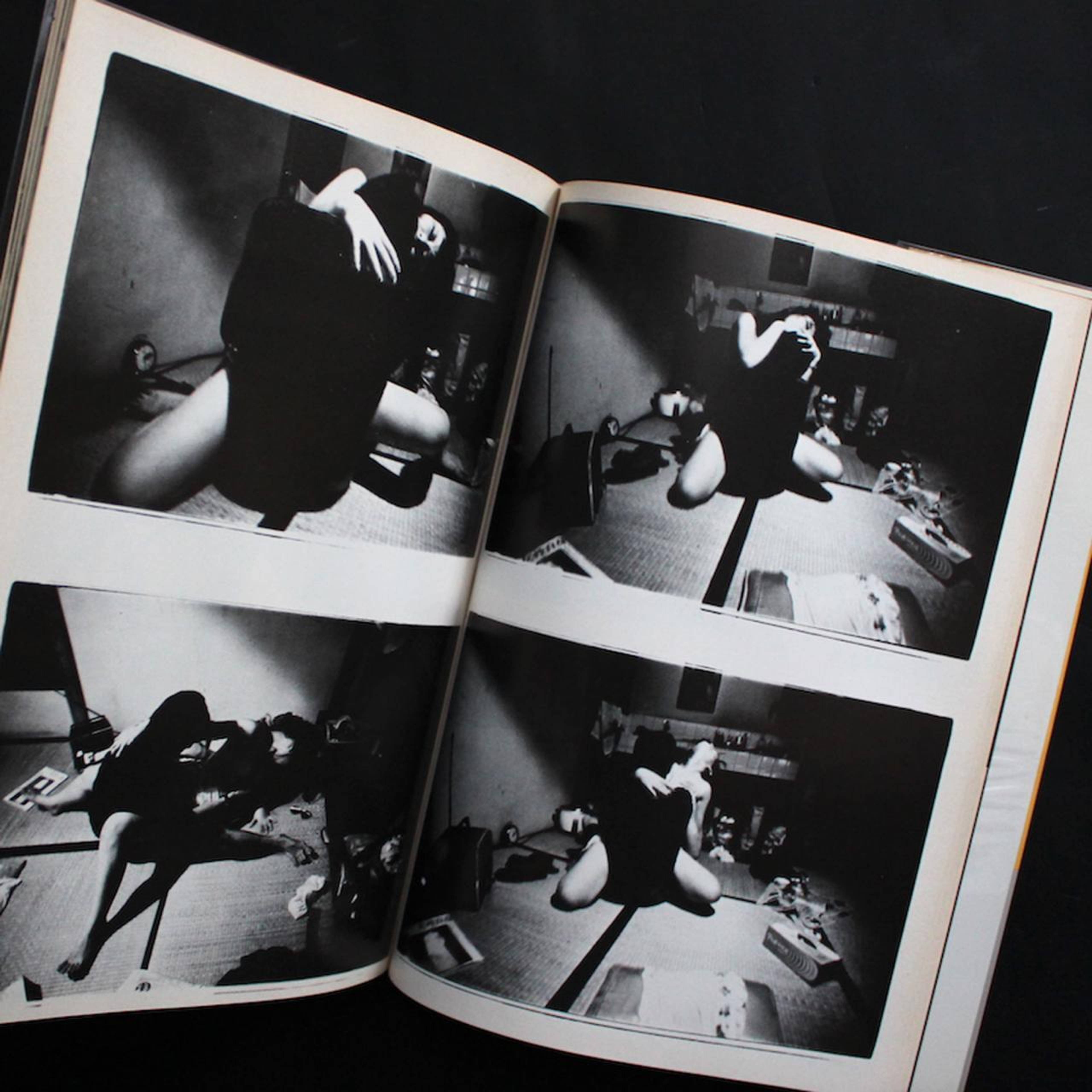

Spread from Izumi Suzuki, I-Novel (私小説), 1986. Courtesy: Byakuya-Shobo, Tokyo. Photos: Nobuyoshi Araki

___