Charting Jim Shaw (*1952) can seem like a fool’s errand, so wide in idea and medium are his gentle collisions of culture. “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” is a concise exhibition within a series of rooms, two each of paintings, drawings, and video installations. As the title underscores, the effect is one of portrait and timeline, journey and mirror. The title is a famous line from William Faulkner’s novel Requiem for a Nun (1951), and witnessing Shaw look towards that novelist feels unsurprising. Both, in their separate fields, are unafraid of vernacular and cerebral intermixing, welcoming the grotesque and the unconscious with meticulous execution.

Within these works, images and concepts are overlaid with the topical, the art-historical, and the popular. The sketches and paintings are exacting and cover a range of illustrational styles, from those of mid-20th century men’s magazines, to underground comics, on towards advertisement – all with a dash of Hieronymus Bosch. Everything here originated over the last decade, and one can read through the show a general move from feelings of unity and hope towards those of division and despair. That Faulkner line was paraphrased by Barack Obama in his speech “A More Perfect Union” in 2008, a moment of seeming racial reckoning that feels now like a delusional blip.

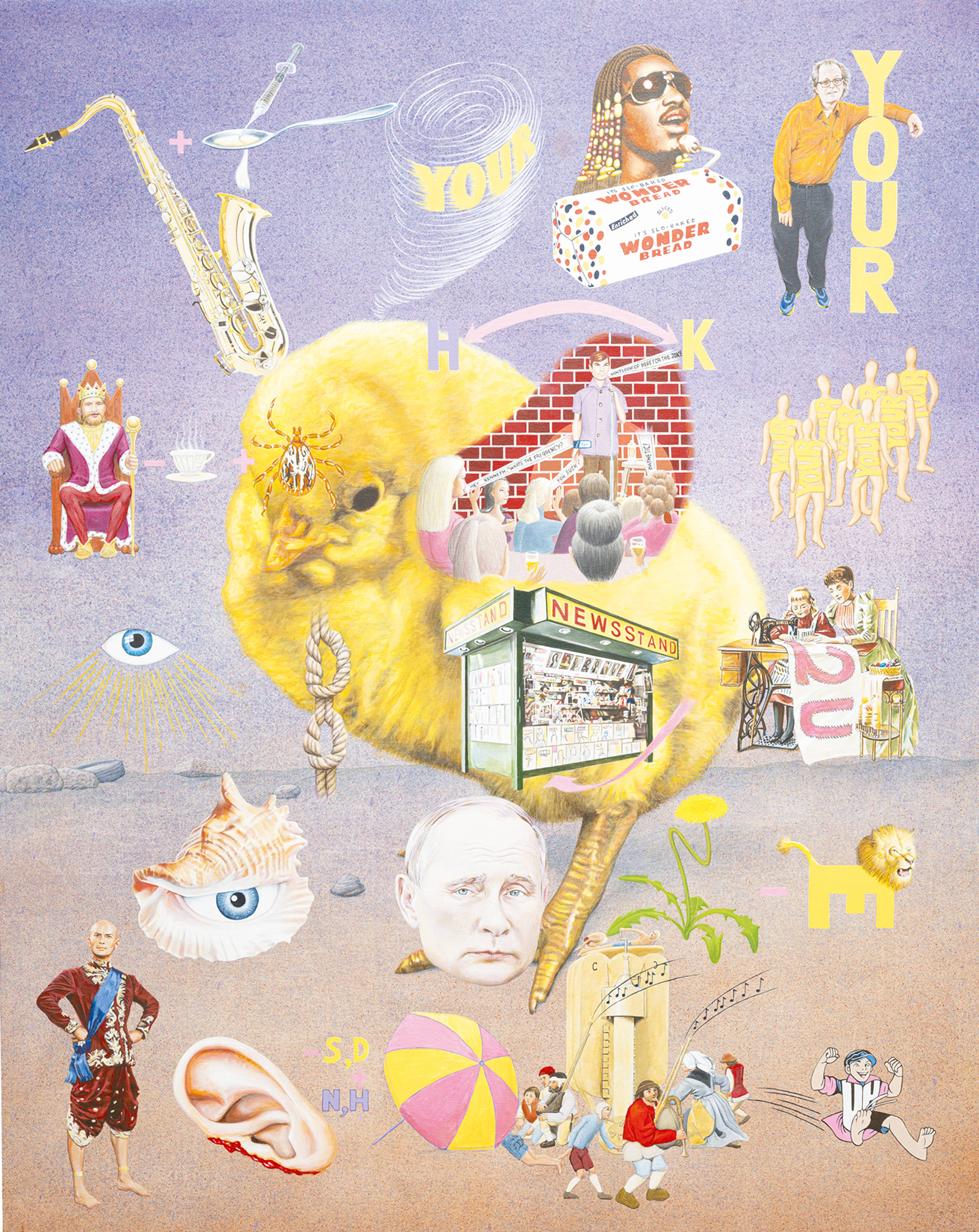

Political figures feature prominently across the twelve paintings and 145 “Study Drawings” (2013–23), and are of a type; repetitions of US Supreme Court Justice and accused rapist Brett Kavanaugh; Vladimir Putin; and various US Senators. In one work combining projection, painting, and children’s book-style informational flaps (St. George and the Dragon 2, 2019), George W. Bush heroically brandishes the head of Saddam Hussein, like the executioner in Caravaggio’s Salome with the Head of John the Baptist (c. 1607). And, yes, Trump is here, in a series of portraits of power, that are, astonishingly, some of the most beautiful and truthful in recent memory.

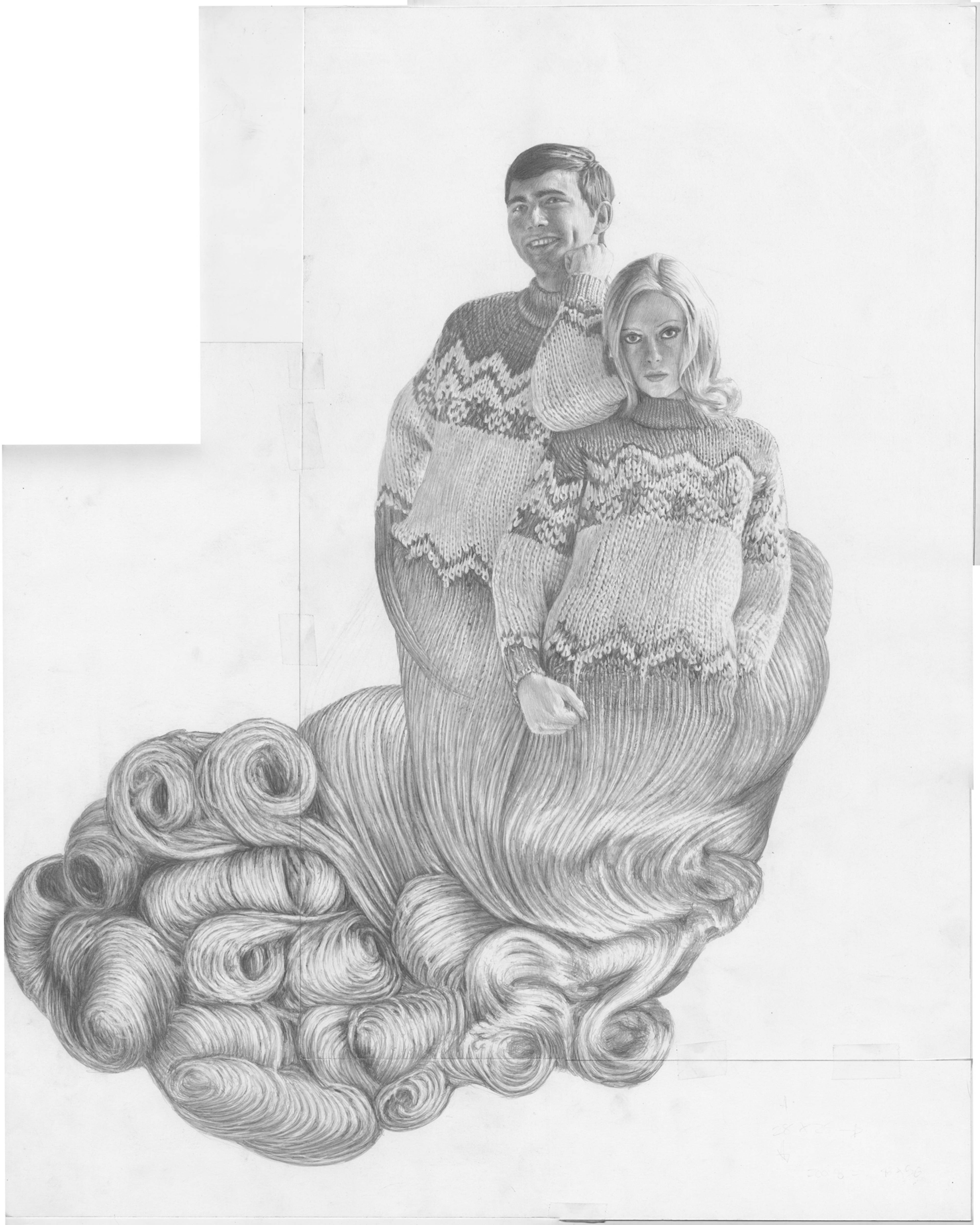

Since his early series, “Distorted Faces” (1978–85), Shaw has been interested in the effect of warping images of renown, and he has long looked at the visual relation of hair to power (see: his installation and 2017 exhibition The Wig Museum at the Marciano Art Foundation, Los Angeles). The three framed, intimately scaled ink works (Trump Distortion #1, #2, #4, all 2017), as well as the graphite studies in vitrines, reveal Trump, a lifetime huckster and probable future dictator, to be a perfect subject for Shaw, and the artist as his perfect executor. His hair peaks and loops like freshly whipped egg white, a voluminous and out-of-control rococo character unto itself, in high opposition to their subject’s actually thin combover. The faces grimace, grin, and contort in rage, but as caricatures, each relates directly to viewers’ lived memories. These depictions fashion Shaw as the unnamed sculptor of Ramesses II in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s sonnet “Ozymandias” (1818): now depicting Trump “whose frown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, Tell that its sculptor well those passions read.” Shaw’s works capture something that facile depictions of the former president by other artists (Peter Saul’s and Judith Bernstein’s come to mind) have completely missed. Without an ounce of glorification, we witness here a certain lost art of history painting, a revelation of character and politics, without becoming agitprop or farce.

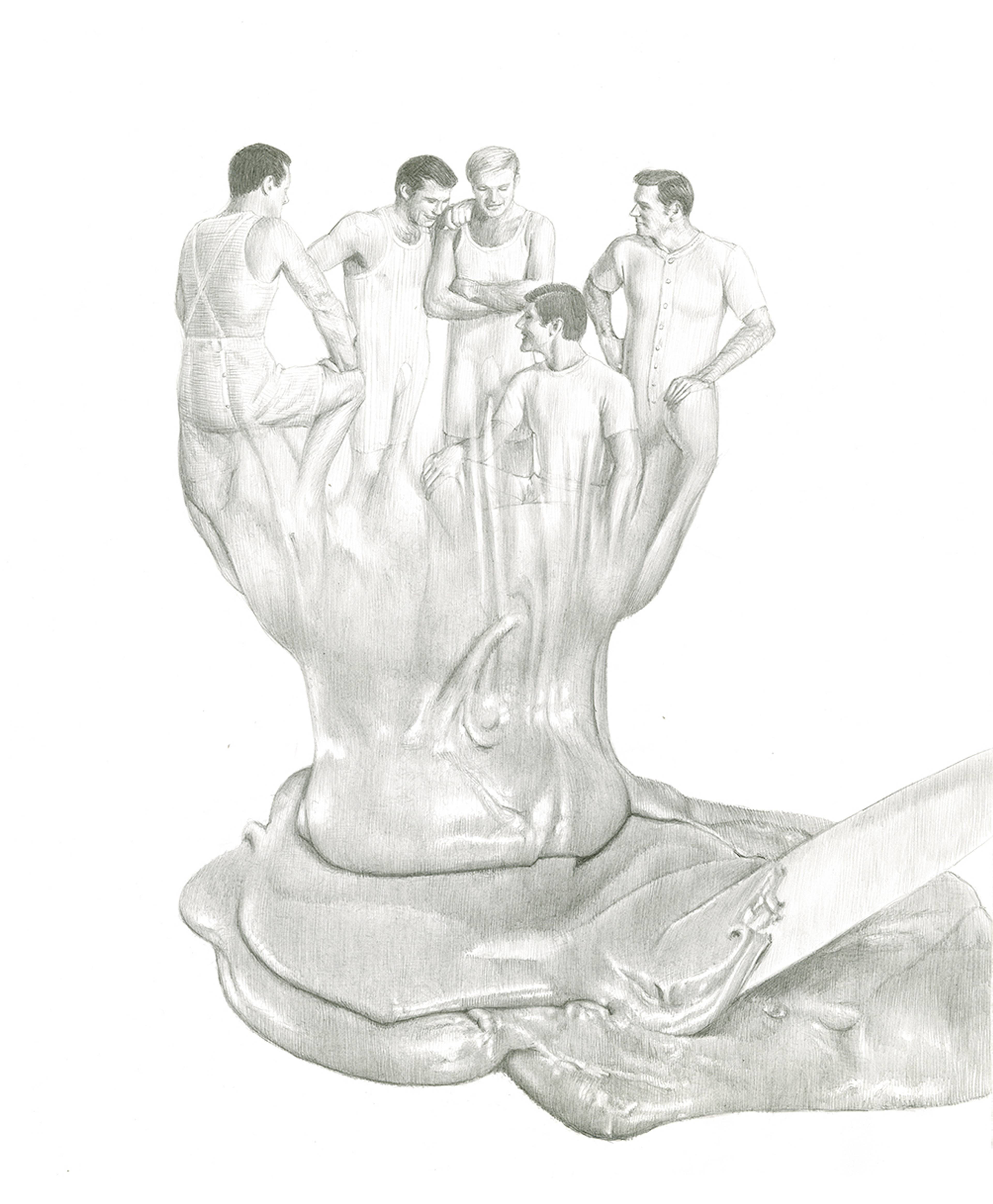

Study for The Pour, 2016. Courtesy: the artist and Gagosian

Mnemonic device #2, Third Stone From The Sun, 2022, acrylic on muslin, 137 x 109 cm. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: Christine Clinckx

Study for The Ties that Bind, 2017. Courtesy: the artist and Gagosian

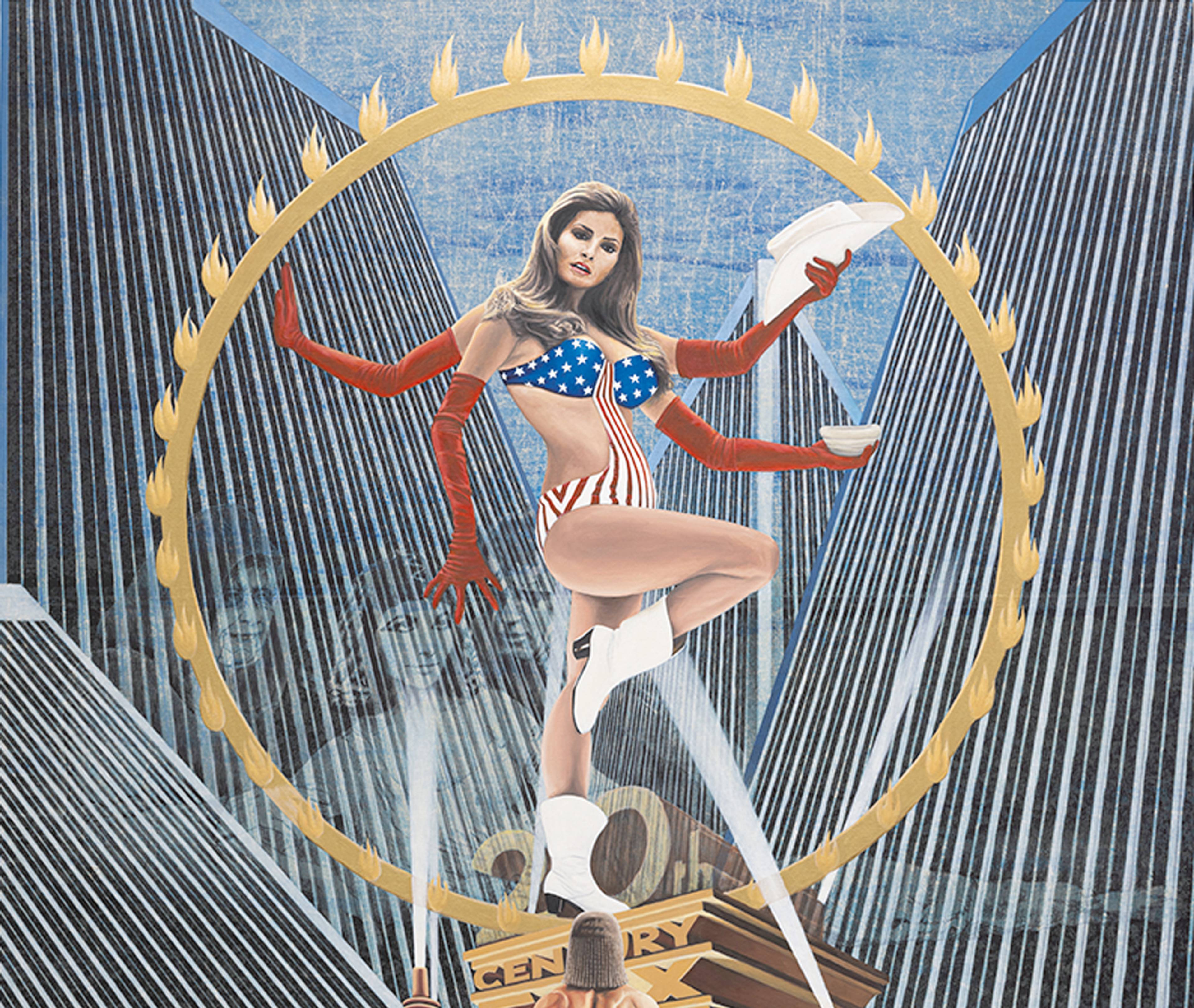

That time might let any of these personalities recede and allow future generations to enjoy these works with less context might seem naïve. Yet, time and geography have worn the edges off the specific all across art history. What deep knowledge or vested interest do we have in Velasquez’s Spanish court figures? How many people visiting this show in central Switzerland recognize in Shaw’s The Bridge (2021) the cast of the iconic American sitcom I Love Lucy (1951–57) or 60s sexpot Raquel Welch? We understand types, and we have enjoyed the forms from this specific show across generations. As an encyclopedia of blurred documentation, this exhibition has the distinct feeling of the digital scrolls that we unfurl in our hands all day long. Working with the tools of five centuries of painting and two centuries of mass media, Shaw not only makes a case for the continuities through which the past informs the present; walking us from post-War US-American hegemony, through the missteps and revelations that followed 9/11, and onto the precipice we seem to overlook today, he also shows them in physical form. If, as Shakespeare wrote, “the past is prologue,” we have both everything and nothing to fear.

___

“The Past Is Never Dead. It’s Not Even Past.”

Kunsthaus Biel Centre D’art Bienne, Biel/Bienne

9 Jun – 25 Aug 2024