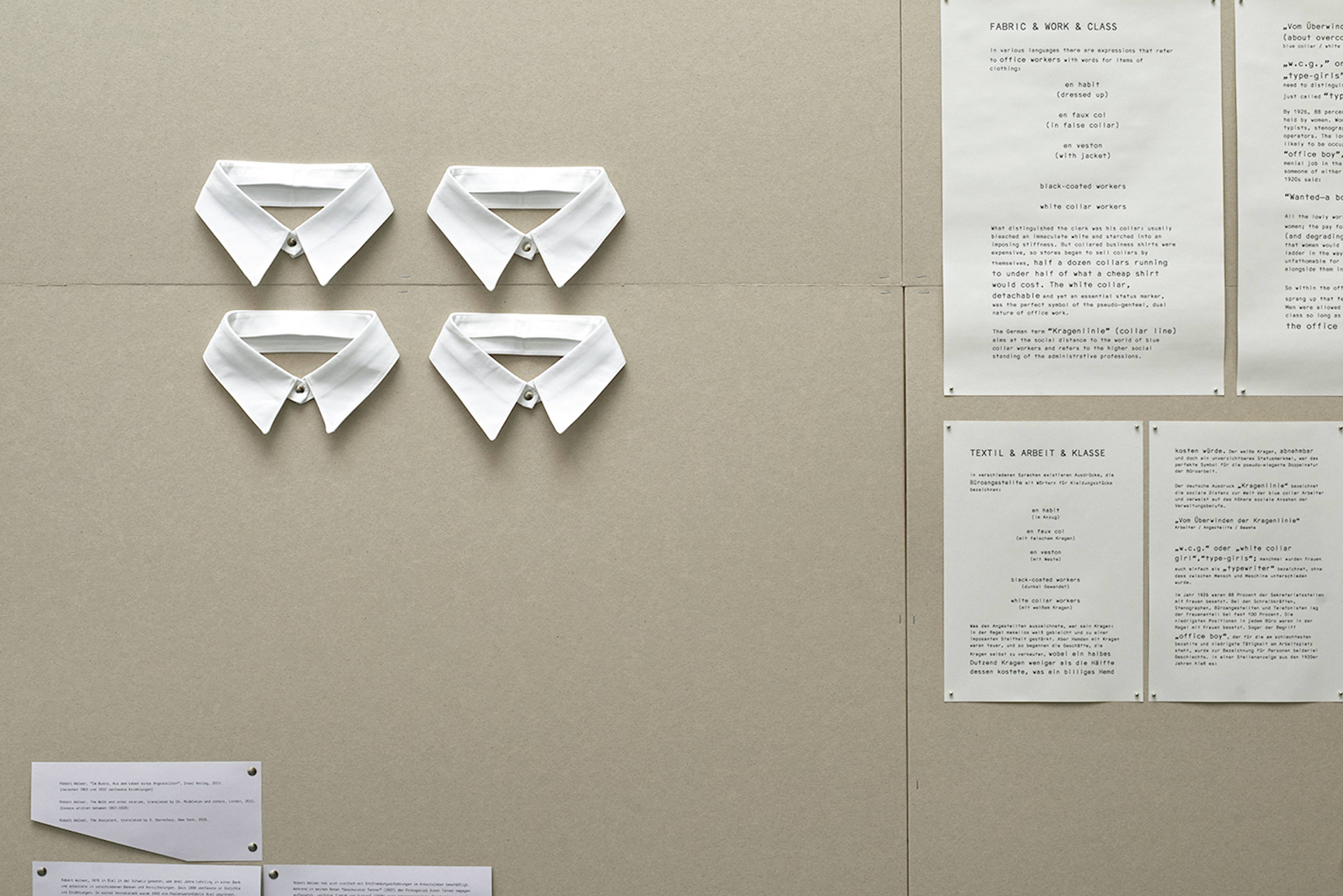

How do folding fans relate to office equipment, textiles, and the history of computing? Katrin Mayer’s (*1974) research exhibition “#c0da comptoir #fanny carolsruh” unfolds a vast informational panorama of women’s work that takes its cue from the history of Karlsruhe itself, before dispersing into the minutiae of administrative regulations and the central role of women in developing computer technology. Installed on austere, cardboard-clad walls that slice through the Kunstverein like the indents of code editors, we find a succession of printouts that blend historical texts and images with Mayer’s own reflections. At the heart of these constellations is c0da.org, an ongoing project that links the lives of early women programmers and feminist writing practices. During her fellowship at the Berlin Artistic Research Program, Mayer invited various collaborators to revisit these herstories together, opening up an inter-generational dialogue that spanned long-term co-conspirators, such as artist Eske Schlüters and philosopher Eva Meyer, and younger artist-authors like Luzie Meyer, Sophia Eisenhut, and yours truly.

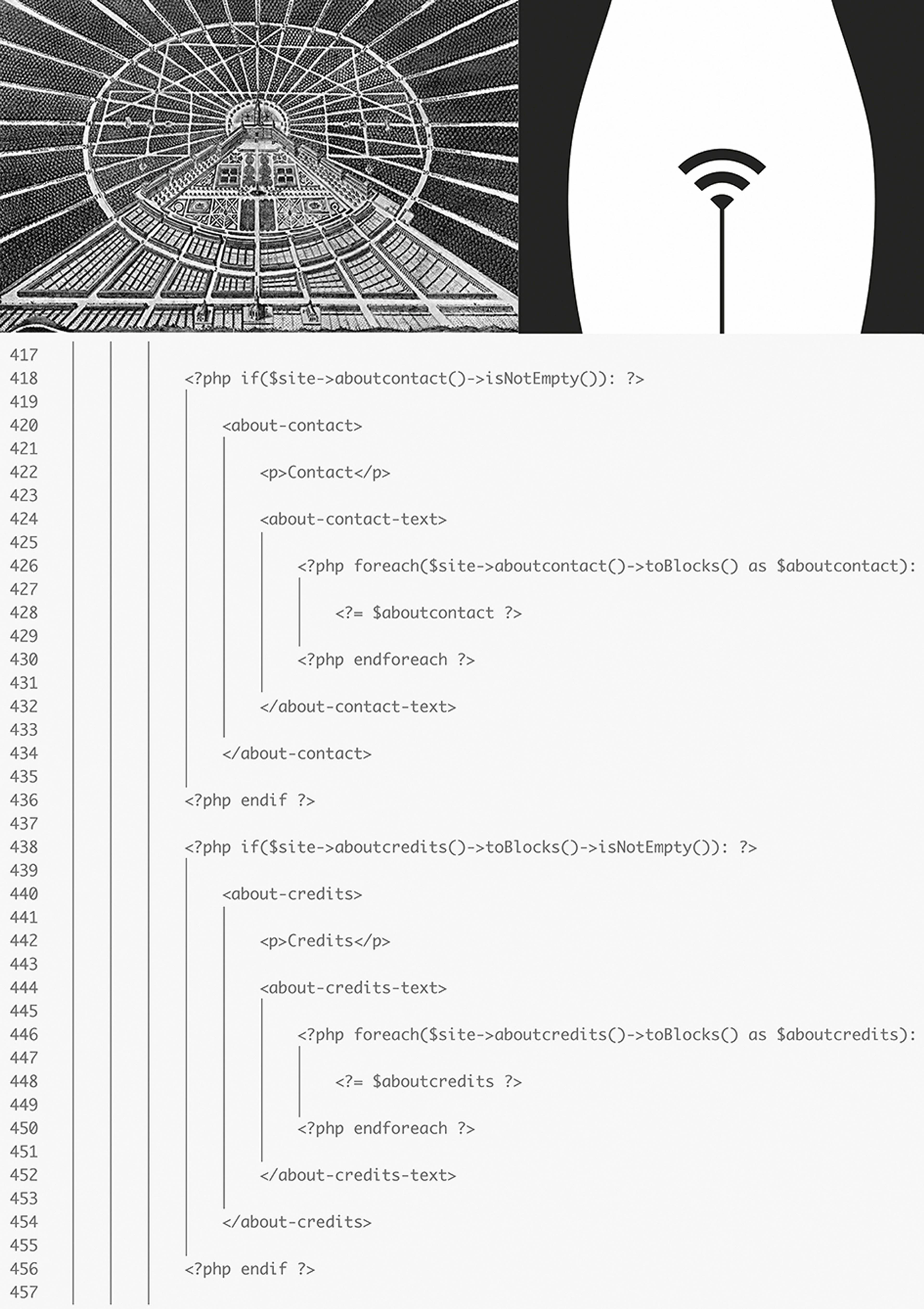

From Karlsruhe’s fan-shaped layout to Victorian folding-fan codes and the coding of early programmers, much of the material here is connected via semiotic slippages and branching etymologies, its linkages navigable but non-linear. The linchpin holding it all together is Mayer’s video essay convulsa or The Need for Each Other’s Relay II (2024), which summons under-recognized figures like Ada Lovelace, often credited as the first woman programmer, and Grace Hopper, who developed some of the earliest compilers that allowed humans to communicate with computers in English. Here, they serve as springboards for articulating a feminist vision of authorship that ensues from the impossibility of an essentialized feminine subject and pleads for a more unruly, networked form of writing. Among the contributions by Mayer’s collaborators, Jasmina Metwaly’s Zeros (2022) appends the essay’s NATO-centric bent by reflecting on numeric forms between Eastern and Western Arabic. Meanwhile, Sophia Eisenhut’s software warfare – EX PONTO BITCHES (2022) complicates convulsa’s emancipatory arc by pointing out that Hopper also laid the groundwork for the calculations that annihilated around 200,000 lives in Hiroshima and Nagasaki: “Men may have dropped bombs, but it was women who told them where to do it.”

Kathrin Mayer, The fanny Book of Carolsruh, Chapter 3. Installation view, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, 2024

Looming large in the background is OG cyberfeminist Sadie Plant, whose landmark book Zeros + Ones: Digital Women + the New Technoculture (1997) highlighted a distinct affinity between Western women and automated machines. This wasn’t just rooted in the historical suppression of women’s agency, but, more crucially, in the transformation of labor markets that allowed women unprecedented opportunities to assert their autonomy. From the “computers” drafted into telecommunications firms during the world wars to the secretaries taught to type in rhythmic patterns “more akin to the abstract beat of drumming and dance,” these workers began articulating a new approach to technology and language. And for Plant, a key turn in this feminist genealogy was the emergence of hypertext, which, as a language of footnotes and absences, allowed users to spin intricate webs of links to all the information that’s missing and must be excluded from any unified body of text – from any text that is one, so to speak.

Fast-forwarding three decades, Mayer’s project almost reads as an homage – albeit with the caveat that art, as art, always and inevitably speaks of itself. Whereas Plant saw yesteryear’s secretaries as the harbingers of a profoundly alienated yet novel digital consciousness, Mayer’s narration of women’s work doubles as an ambivalent commentary on the status of artistic research itself – wavering, as the genre does, between a genuine search for alternative ways of knowing and assimilation to the strictures of intellectual labor in a knowledge economy: art as the bureaucracy of dreams. This conflict is staged in what could be described as the show’s climax. At the end of the paper trail, we encounter Clothed, RECEPTION (2010). Reprising a site-specific work originally developed for the defunct Berlin gallery Reception, it consists of a 1:1, sewn-fabric copy of the gallery floor, now draped just below the Kunstverein’s ceiling. As the light filters through, its striped surface flickers and contorts, inducing a viscerally what-the-fuck convulsion of space.

Kathrin Mayer, Archival Floor, Clothed, RECEPTION, 2010. Installation view, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, 2024

Collage: Katrin Mayer, image editing: Ana Aguilera, Code: Anna Cairns, Source: Stadtplan / city layout: Stadtarchiv Karlsruhe

Whither the fate of embodied experience under the regime of art as knowledge production, we might ask. Here, it becomes clear that Mayer, who also works as an exhibition designer, has deliberately deferred the gratification traditionally gleaned from discrete artworks. Instead, the show consists in an aesthetic experience based on the hypertextual decoding of partial overlaps, slippages, and resonances between disparate strands as they accumulate across time and space. Meanwhile, the non-verbal messiness of bodies and politics beyond the text is forcefully acknowledged, though not necessarily dealt with. Eerily, we find ourselves in the midst of a post-conceptual analog to the feedbrain: the pleasures of pattern recognition without interpretation, as Plant might say, or an attunement to the rhythms latent in threads of the mind otherwise too short to tie.

___

“#C0DA Comptoir #fanny Carolsruh”

Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe

21 Jun – 1 Sep 2024