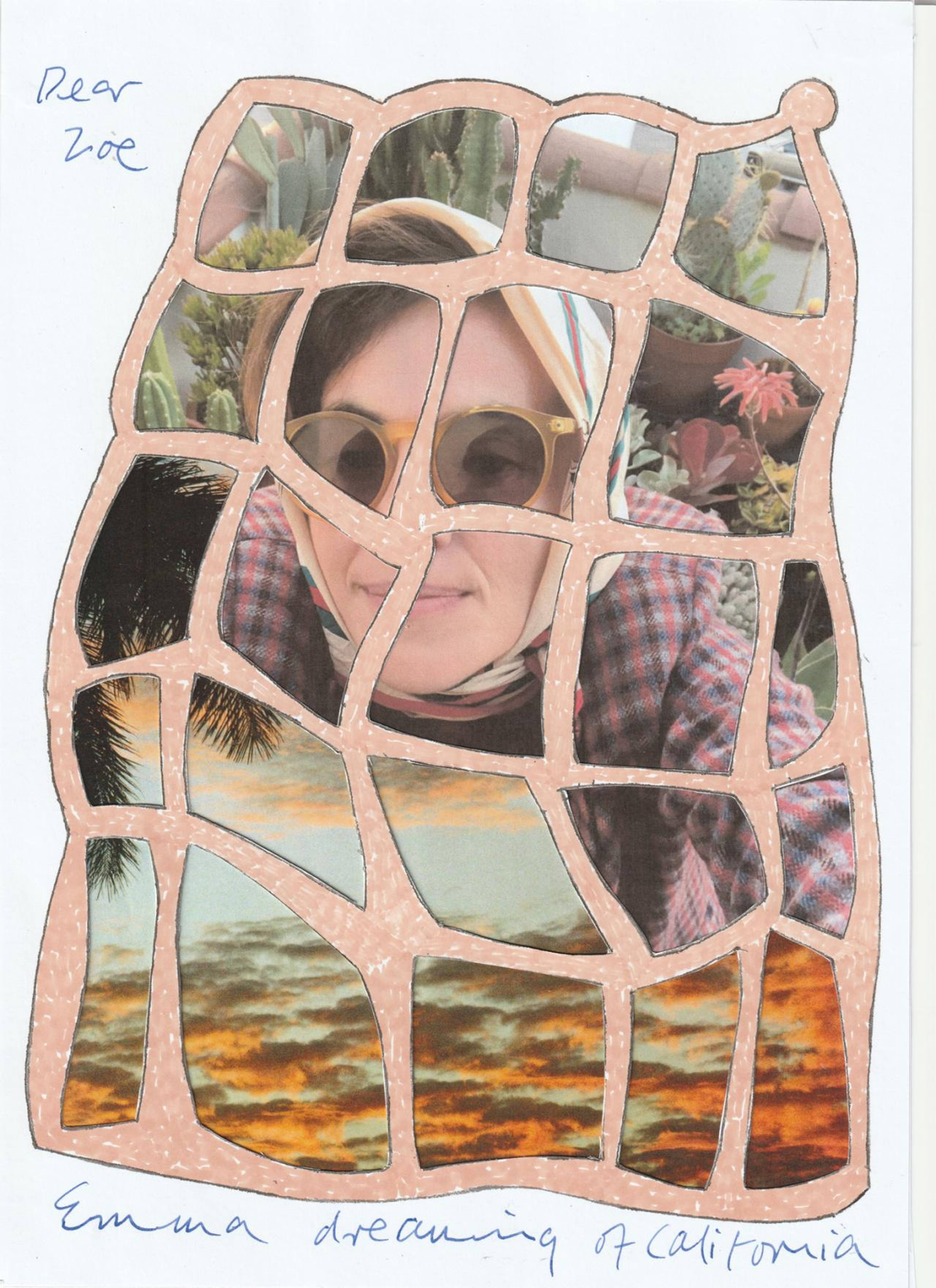

“If only [Emma] Bovary had been aware of self-empowerment,” Marc Camille Chaimowicz (*1947) speculates in one of a series of new collages titled Dear Zoë (2020–23), addressed to the curator of “Nuit américaine,” Zoë Gray. “If only” is the refrain of not only that series, but the whole exhibition, really, and perhaps even Chaimowicz’s practice across the board, characterized as it is by feelings of loss and longing, a kind of twilit wistfulness. The collage includes a Helmut Newton photograph of a woman sitting with her legs spread, staring carnivorously ahead at a shirtless man. Of course, the enduring appeal of Madame Bovary (1856) is Emma’s lack of empowerment, just as Chaimowicz, with his “if only,” does not intend to rescue her from evergreen demise, but relish in the sweetness of it. Self-empowerment – so what? the artist seems to say, and rightly so: The idea has become its own pathetic fallacy.

It reminds me of the famous “Klopstock!” scene in Goethe’s Werther, in which the doomed Liebespaar exclaims the name of the 18th-century poet as clouds part after the passing of a storm. This, a kind of ur-simulacrum, speaks of Nature as always already lost, its profundity accessible only by approximation through poetic metaphor. While in Goethe, the tragedy of life failing to live up to its image (or the other way around, interchangeably) could still be understood as romantic, eighty years on, the brutal destiny of Flaubert’s anti-heroine has the darker hue of realism.

View of “Nuit américaine,” WIELS, Brussels, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and WIELS, Brussels. Photo: We Document Art

By the time Chaimowicz started working in the 1970s, such pathos-ridden double-thinking of mourning and rejoicing had already been degraded to the status of camp – a tacky excess read reparatively by Susan Sontag as a highly specific form of scare-quoted irony and, to a different but related end, by Eve Sedgwick as “an attempt to assemble nurture out of a realistic fear that the surrounding culture will not provide it.” His installations Celebration? Realife Revisited (1972–2000) and The Hayes Court Sitting Room (1979–2023) have tended to find a place between these two definitions as dandyish affronts to straight taste, a public-private breach to sting bourgeois sensibility, as well as a provocative disregard for modernist distinctions between fine art, decoration, and crafts. While Chaimowicz has always been recognized for his work, he has also, as the exhibition text says, “steadfastly sailed against the prevailing artistic winds.” But winds are fickle, and I wonder if, amid the last decade’s turn towards identity, affect, and the “discovery” of older artists, Chaimowicz’s reception has not also shifted towards hegemony?

Celebration? shows a party scene the moment after the last guest has left the premises: glitter on the floor, empty glasses, a disco ball and pink lights, a photograph of Lenin, ersatz flowers and a feeling of “You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.” With no furniture, the room feels sparse, and whatever emotion or aura that used to emanate from these objects is exhausted. Theoretically, this loss could be read as romantic (Klopstock! If only!), but in so-called reality, hollowness resounds a little too loudly for this fixation with the sad beauty of transience to not come off as slightly morbid.

Marc Camille Chaimowicz, Friday 16th July 2021, 2021, from the series “Dear Zoë (Emma Bovary collages),” 2020–23, paper, 21 x 30 cm. Courtesy: the artist

Sitting Room recreates a version of Chaimowicz’s home as a theater set. But like the party scene, what would have read as an unusual emphasis on the creativity lodged in the idiosyncratic and the everyday, I could not help but relate to the by-now ubiquitous obsession in contemporary culture at large with one’s own past. Whether on social media, in the reconstruction of castles and medieval city centers in Europe, or the long on-going funeral procession that is Britain – Chaimowicz’s home – the modus operandi à la mode is a sentimental end-game. Perhaps this ubiquity goes some way in accounting for the current tendency to subsume artists like Chaimowicz, along with some loose idea of queerness associated with him, into the staging of capitalist individualism as a kind of perpetual sunset. Sentimentality is degenerated charm, and Sitting Room ’s Bloomsbury-esque fireplace and wilted flowers are a case in point for how Britain’s national affect par excellence, too, has wilted.

The critical potential of camp relied on its opposition to modernist doctrines of autonomy and objectivity, an intellectual culture which, it is safe to say, no longer exists. But when all of the arts wallow in nostalgia and pathos and everything has for so long been repeated in scare quotes that scare-quotes no longer register, I am sad to say that Chaimowicz’s work loses much of its bite. These days, bringing your private emotions into a public space, however camp, is not a form of subversion, but a business model.

Marc Camille Chaimowicz, The Hayes Court Sitting Room, October 2022. Courtesy: the artist and Cabinet, London. Photo: Mark Blower

___

“Nuit américaine”

WIELS, Brussels

17 Feb – 13 Aug 2023