It’s a brief walk from the house where Margaret Raspé has lived and worked since the 1970s, through a bourgeois neighborhood of single-family residences and domestic pressures, to Berlin’s Haus am Waldsee. There, the ninety-year-old artist’s first institutional retrospective, “Automatik,” spells out a practice intended to transcend the repetitive tasks of her Alltag (daily routine) as a housewife and mother.

At the outset of her artistic career, Raspé, already a single mother of three, developed her so-called “camera helmet,” or a hardhat equipped with a Super-8 camera, in order to film her housework hands-free. She whips cream into butter in Der Sadist schlägt das eindeutig Unschuldige (The Sadist Beats the Clearly Innocent, 1971), breaks an egg for a cake in Backe backe, Kuchen (Bake, Bake, Cake, 1973), and does the dishes in Alle Tage wieder – let them swing! (Every Day Again – Let Them Swing!, 1974), unseen throughout, yet imminently present. Every movement, every view is her own, conveying a self-possessed focus that turned the home’s confinements into a space of artistic agency.

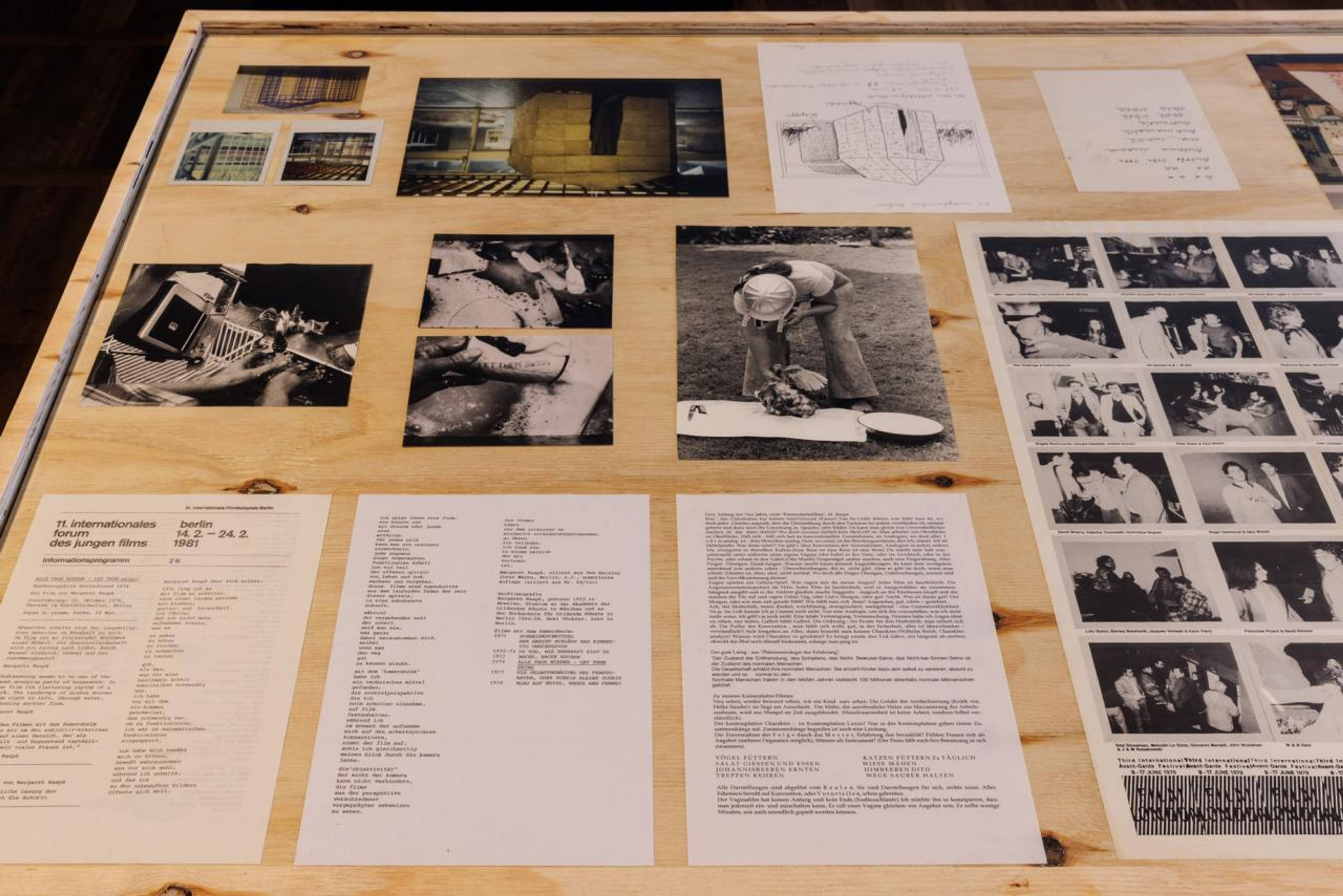

View of Margaret Raspé, “Automatik,” Haus am Waldsee, Berlin, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and Haus am Waldsee. Photo: Frank Sperling

Long before terms like invisible labor, care, and the Anthropocene entered a wider parlance, Raspé’s work was complicating modern oppositions between nature and technology. In a chance encounter with a local beekeeper, for instance, she observed the likeness of the grids of honeycombs to television pixels, which she merged in two sets of work, Videomiel/Videohonig (Video Honey, 1990–2023) and Fernsehfruhstuck (TV Breakfast, 1994–2023), mounting honeycombs on small, mobile monitors. The volume of televisions, turned on and respectively suspended from the ceiling and arranged as a foursome on a tabletop, is kept low, echoing the visual distortions as a unparsable hum.

In a conversation with the exhibition’s curator, Anna Gritz, Raspé is sharp, funny, and, in spite of – or perhaps owing to – her advanced years, tirelessly angry. “I was deeply unsatisfied with my role as a housewife. I read art books while the children slept, but couldn’t even think about making art. My life was restricted, I couldn’t stand it. I was filled with real rage.” It echoes the “cold fury” in which Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote her Manifesto for Maintenance Art (1969), which demands that the feminine labor of upkeep be set on equal footing with the masculine “pure individual creation” of the avant-garde, or the escalating frustration with which Martha Rosler ticks off an alphabet of kitchen implements in the video performance Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975).

Margaret Raspé, Fernsehfrühstück (TV Breakfast), 1994/2023. Installation view, Haus am Waldsee, Berlin, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and Haus am Waldsee. Photo: Frank Sperling

If life as a homemaker is a cause for indignation, death as a place of refuge also plays a prominent role in the depiction of domestic life in other work of that period. The title character in Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), a Belgian widow and at-home sex worker, tries to control herself and her existence through the exhausting programming of her daily chores, only to stab one of her male clients in the film’s penultimate scene. Death at Raspé’s own hands makes an appearance in the video Oh Tod, wie nahrhaft bist du (Oh Death, How Nourishing You Are, 1973), which depicts the slaughter of a chicken. “Whether you cut a salad or a piece of meat, you end something,” Raspé remarks. “It’s an affirmation of the end, of death. Making a schnitzel is death in a pan.”

While Raspé herself was never an outspoken member of the feminist art movement, her works form a continuity with practices from that climate. Along with reclaiming her Alltag’s endless, automatist chores, her work champions a silent opposition, manifest throughout the exhibition as a low hum, to the conventions of both femininity and art-making. “Automatik” underscores that it is the constant mental and physical availability expected to motherhood that is seemingly incompatible with a career as an artist, which demands its own immediate and tireless readiness, be it to one’s work, one’s patrons, or one’s muse – only to subvert the distinction. Motherhood, of course, is not the problem; the obstacle, rather, is the old-fashioned, patriarchal, romantic fantasy of the artist as a genius unencumbered by social mores and obligations to others, the conservatively coded family foremost among them.

Still from Oh Tod, wie nahrhaft bist du (Oh Death, How Nourishing You Are), 1972–73, super 8, color, silent, 15 min. Courtesy: the artist und Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin

Raspé’s poem “Unterbrechungen” (Interruptions, 1982), makes the tensions of lived time almost somatically palpable: A day passes as a list of endless tasks, its author running up and down the stairs, opening and closing doors, until, at nine o’clock in the evening, her husband comes home to ask: “What did you actually do all day?” The poem recalls Anna Swir’s “Maternity,” written for her daughter that same year, about the Polish poet’s refusal to die in becoming a mother:

“You are not going to defeat me,” I say.

“I won’t be an egg which you would crack

in a hurry for the world,

a footbridge that you would take on the way to your life.

I will defend myself.”

View of “Automatik,” Haus am Waldsee, Berlin, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and Haus am Waldsee. Photo: Frank Sperling

___

“Automatik”

Haus am Waldsee, Berlin

3 Mar – 29 May 2023