When entering Mikołaj Sobczak’s “Sun, Moon, Mercury,” one is immediately confronted by Luigi Mangione in a red cape, with one fist lunging forward in Superman’s signature pose. The young American man accused of killing the CEO of UnitedHealthcare, the United States’s largest for-profit health insurance provider, is flying out of a beaming sun over the personage-filled odyssey of Sun (Magical Realism) which hangs between two other towering 2 x 4.77 m paintings, Mercury (Underground) and Moon (Propaganda) (all 2025). These three principal works, alongside a collection of collages, make up his 2025 solo show at the Salzburger Kunstverein.

The canvas is dense with dozens of notable characters flanking Mangione, a stylistic trademark unifying the pieces in the show. Just consider (among the many others) German Romantic hero Goethe lounging on a garden, opposite the levitating Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. To their left, the red dress-adorned woman pulled from Nina Vatolina’s 1941 Russian, anti-fascist poster, fiercly raises her right arm (like the “Magician” tarot): these three figures alone create a scene that spans nearly two and a half centuries and three distinct geopolitical territories.

Amid this sprawl of references, Mangione’s presence, still hot in the cycle of TikToks and TV news segments, feels like temporal whiplash. Just weeks earlier, the fashion Instagram account, Diet Prada, made a post to their nearly 3.5 million followers calling his trial outfit, “very Prada Spring 2013–coded!” It referenced his crimson red sweater, slacks, and sockless loafers, which do in fact hold a close resemblance to the Milanese fashion house’s earlier runway look. Through viral posts and online discourse, Mangione’s identity has expanded beyond that of political dissident; he’s become a fashion icon, a meme, a media spectacle. And now here he is, center stage in Sobczak’s painting, in a cape torn from Clark Kent mid-flight, colored in a red recalling his courtroom sweater. Still shackled by chains on wrists and ankles, he somehow defies their restraint – possibly with the bulging muscles that show from under his tattered rags.

View of “Moon, Sun, Mercury,” Salzburger Kunstverein, 2025. Courtesy: the artist and Salzburger Kunstverein. Photo: kunst-dokumentation

For a generation that exists more online than ever, steeped in the righteous scroll, this kind of rapid canonization – where a memeable, ambivalent figure from the algorithmic present is pulled into a mythic, painterly past – is disorienting. It feels too plugged in. Too now. Sobczak’s gesture seems more suited to a fleeting Instagram post than a monumental painting. Yet Luigi’s magnetism is undeniable: he embodies so many seductive traits of the archetypal hero.

And just as heros do, Mangione enters the scene as forces of good and evil face off. On the right, a Bezos-Nosferatu amalgamation – the CEO’s face with devilishly pointed ears and fingernails – slinking up from the bottom of the composition with a giant pair of scissors in hand. He’s poised to cut the matted and overgrown hair of Sobczak himself, resting pensively on a bright green Uber delivery cooler. Opiate packs rain down against a flesh curtain patterned with pulsing veins. The dark shape of a police man grasps onto the reins of his rearing black horse.

These aren’t figures of clandestine evil, but ones legitimized and sustained by governments and mainstream industries. But other than that, they feel loosely related to one another on the canvas. Are the police enabling the opioid epidemic? Is Amazon just another state enforcement power? Is Sobczak himself being submitted to the same exploitative labor practices as workers in the gig economy? The artist has created a cast of villains who haven’t yet plotted their master plan.

The composition hovers between memory and hallucination, recognition and distortion. It is a fraught, suspended awareness.

On the left of the composition, a network of grassroots, non-establishment responses to oppression emerges. A szeptucha, Polish for “healer,” wearing a black head scarf is positioned above an anthropomorphized mandrake, rooted among other toxic herbs like datura and belladonna. As Sobczak explains in an interview with the Kunstverein, herbal poisons given to unjust landlords was one of the few forms of resistance available to peasants under feudal rule. That same healer, with small a match and tinder-filled pouch in her up-turned palms, is ready to perform bańki, a treatment similar to Chinese cupping. She is tending to the LGBT+ activist Tomek Pawłowski-Jarmołajew, whose beaten back is exposed to the viewer – a reference to an altercation in early 2025 that he has connected to homophobia. Close to the black-and-white Goethe laying in the toxic herbs and Vatolina’s fierce warning against fascism after the Nazi’s invasion of Russia, the artist also paints Joe Kilpatrick, an enslaved man who adopted a black child in the early 19th century while working on an American plantation, an act of resistance in the form of kinship.

While the szeptucha and the herbs have explicit references to mystic practices, these other figures introduce issues from the Soviet era and the American Antebellum South. The huge thematic space the paintings inhabit expands the geographic and temporal axes of Sobczak’s argument in a way that risks diluting the potency of the magic being administered. In compressing and stuffing spatial-temporal spans, the paintings end up busy with images and symbols. They are equally teeming with a medley of styles, as the artist remains very true to his visual sources even down to their compositions: black-and-white figure studies, poster replications, and reproductions of historical paintings all exist within the same visual plane. It’s an acrylic-medium extension of his collage work, also shown in the exhibition, that speaks to both his technical and conceptual processes.

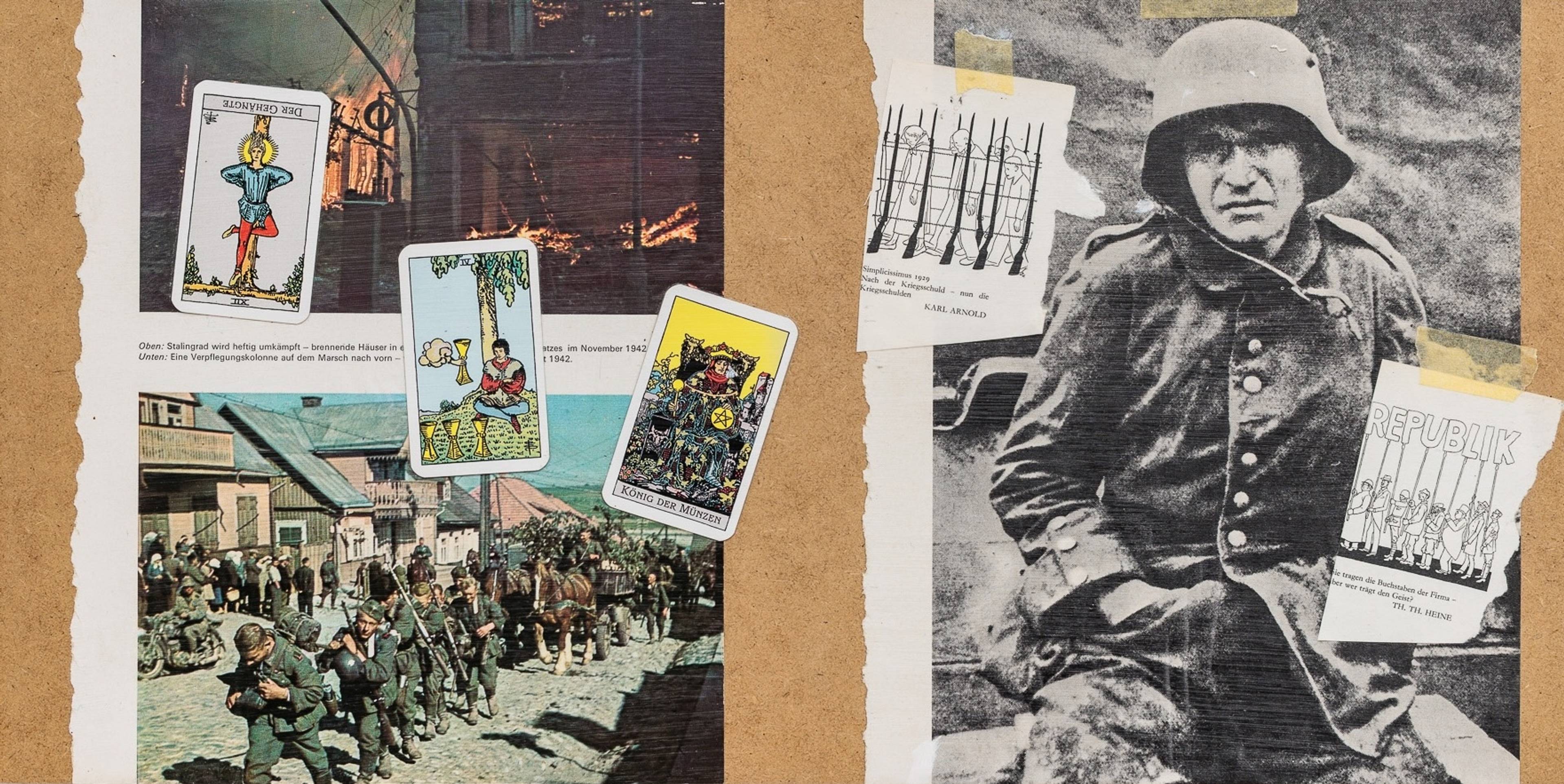

Tarot, 2025, collage on masonite. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: kunst-dokumentation

Collages on the back of Moon (Propaganda), 2025, acrylic on canvas, 200 x 477 cm. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: kunst-dokumentation

To reference the title of the painting, the coexistence of disparate figures and styles is precisely what evokes the feeling of stepping into a world of magical realism. The eclectic cast with their frenetic styles, dynamic postures, and layered interactions collectively construct a kind of fantastic realm. Yet even supernatural worlds have rules. What has sustained magical realism in the past is not a lack of structure, but the presence of a unique internal logic – an underlying mechanism that governs how magic operates within the real. Sobczak’s work inhabits this space, but as his worlds expand ever more rapidly in every direction a reference leads, the rationale begins to fray towards mere juxtaposition.

And yet, the hodgepodge of references are all immediately accessible – conjurable within seconds through a web browser. In this way, they don’t abide by Sobczak’s logic, but of the logic of the 2020s. In this paradigm of instant searchability, the artist’s use of collage and referential density is not merely aesthetic, nor a harkening to occultism, but it creates a living archive echoing our disorienting collapse of past and present. “The fleeting sense of time that was the signature of the broadcast age,” Mark Fisher once wrote, “when cultural moments could be replayed only in memory and dreams – has given way to a time when nothing ever really dies, and every encounter can be deferred … We are haunted in a certain way by the loss of loss.”

Although he wrote this in 2014 for Spike’s “History in a Time of Hypercirculation” Issue, over a decade later, the reference-recycling culture Fisher diagnosed has only intensified. Seeing the Bezos-Nosferatu alongside a screaming mandrake root feels oddly similar to stumbling upon Mangione, an AI-generated kitten, and the latest war updates all in one Instagram update.

Mercury (Underground), 2025, acrylic on canvas, 200 x 477 cm. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: kunst-dokumentation

With this mercurial stimulation it’s easy to go numb. Marshall McLuhan advised in 1964’s Understanding Media: “we have to numb our central nervous system when it is extended and exposed, or we will die. Thus the age of anxiety and of electric media is also the age of the unconscious and of apathy.” Sobczak’s paintings operate within this terrain of overstimulation and psychic self-preservation. By gathering healers and the wounded, villains and lackeys, lords and mystics into a single visual plane – removed from their context – the composition hovers between memory and hallucination, recognition and distortion. It is a fraught, suspended awareness.

This space between the conscious and the unconscious is precisely where memory forms – and that’s part of what makes the hazy rules of Sobczak’s history paintings ripe for the contemporary moment. The genre has rarely attempted to depict history objectively; instead, it has assembled facts, symbolic figures, allegorical gestures, and emotional charge to reflect the meaning of history as shaped by memory, myth, or ideology.

There’s a familiar, ambiguously attributed adage: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” So what does “remember” mean in an age when the past isn’t allowed to be forgotten, but continually reconjured in algorithms, social media feeds, and nonstop news cycles? Perhaps Sobczak’s release of heroes and villains offers an answer. In his work, the archetype becomes a storage device for collective memory: compressed, distorted, and compulsively repeated, it forms a provisional link between the ancient and the instantaneous, the canon with the viral.

___

This text was written during a month-long Writer-in-Residence program at the Salzburger Kunstverein, which was awarded in partnership with Spike. Read Greta Rainbow on Laila Shawa and Esben Weile Kjær here; a text from Gabrielle Schwarz is forthcoming later this year.

Mikołaj Sobczak

“Moon, Sun, Mercury”

Salzburger Kunstverein

17 May – 13 Jul 2025