Paul Pfeiffer (*1966) first appeared in the late 1990s and quickly became lauded for brief, looped videos of sports figures with much of the background effaced, typically projected at tiny size or exhibited on the small viewscreens of the cams that might conceivably have shot them. The images tended toward the agonistic or ecstatic, paroxysms of celebration or intense action that turned into vaguely unnerving oscillations. The athletes involved were typically Black, emphasizing the paradoxical placement of the otherized body at the center of American spectacle. Never a market darling – what conceptual video artist is? – Pfeiffer has remained formidable ever since, producing a slow and steady series of works that rarely stint in their power. While sports has throughlined his career, he swiftly pivoted to dissect movies, television, and other genres inseparable from the construction of the imagery at the crux of American culture, his efforts crystallized in this exceptional mid-career retrospective.

Erasure remained one of Pfeiffer’s early signatures, with a particular focus on the otherized body. In 24 Landscapes (2000), Marilyn Monroe has been scrubbed from well-known photos of the icon on the beach, leaving behind only the sand and tides, while the three video works comprising The Long Count (2000–01) feature the mostly white spectators of famous fights involving Muhammad Ali, gaping and shouting at his and his opponents’ barely perceptible ghosts. That same year, Pfeiffer made – pace Bruce Nauman – Self-Portrait as Fountain, a recreation of the shower from Psycho (1960) as it might have been viewed on set. Mics, lights, and cameras peek behind the curtain with a violating air as water gushes continuously, a MOCA guard sitting at the ready to deter any visitors’ voyeuristic desires to peek themselves. Reality, or what we posit it as, lies shrouded and remote while its image dully radiates, its contents accessible only via a gridded, surveillance-style set of black-and-white feeds.

Paul Pfeiffer, 24 Landscapes, 2000/2008, digital c-prints, twenty-four parts, overall dimensions variable. Courtesy: the artist, Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, and MOCA, Los Angeles

Paul Pfeiffer, “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” 2006–18, matte C-prints, overall dimensions variable

Paul Pfeiffer, Self-Portrait as a Fountain, 2000. Installation view, MOCA, Los Angeles, 2024

Pfeiffer’s virtuosic rendering of communal experience shunts into the terrain not only of cinema, television, and their semi-atomized spectators, but also the archetypal site of actual presence: the stadium. In an exhibition of hit after hit, two of the most extraordinary works form a kind of horizon line on opposite sides of the former warehouse that is the Geffen Contemporary, both primal scenes of Pfeiffer’s fundamental dialectic of absence and presence. For The Saints (2007), Pfeiffer, an American of Filipino descent, arranged several screenings of the 1966 World Cup Final at a full theater in Manila, and, after instructing viewers to cheer for England, meticulously mixed the sonic results into a seventeen-channel recording. Its installation involves three parts: a large, bare room with that audio played at high fidelity and in surround sound; a tiny video of a single, celebrating English player; and, behind a partition, the original match footage and footage of the Manila audiences set side by side. In a surprise inversion, The Saints places the “viewer” in the center of the spectacle, and the effect is almost physically overwhelming – to be the pith of such unhinged joy. Its terrifying edge comes from the power of the madding crowd – that is, from politics – as well as from the techno-sublime, the chorus of voices blurring religion and humanism into an architecture of communal experience.

IMAGE

A recent counterpart to The Saints, Red Green Blue (2022) positions multiple cameras around the University of Georgia’s 92,000-seat football stadium, only to focus on the school’s marching band. Pfeiffer offers no panoramas, no coherent image of the whole, instead using his cameras like probes: They sink deep into the crowd to capture clenched jaws, the band captains’ crisply gesturing hands, ponytails sprouting from baseball caps. Meanwhile, every so often, Pfeiffer abandons the enormous roar for the cheeps of birds and twilight buzz of insects outside the stadium, where, just barely within the viewframe, a cemetery lies practically on the arena’s grounds. Eerie in its stubborn historicity, the graveyard subsumes both Confederate generals and a group of the enslaved who had been disinterred from an antebellum burial ground in 2015, a year before Pfeiffer began teaching at the university. The militaristic aspect of American football is frequently observed, but less so that of their musical battalions: Marching bands, so common to US schools, have their roots in military tradition, which, in the South, means a connection to an unburiable past.

Paul Pfeiffer, Three Figures in a Room, 2015–18, two-channel digital video with four audio channels, color, sound, 48:00 min., dimensions variable

Paul Pfeiffer, Red Green Blue, 2022, single-channel video, color, surround sound; 31:23 min., dimensions variable

Pfeiffer’s work is rare – pointed yet open-ended, brainy yet accessible, and unafraid to tackle the largest of subjects: spectacle, race, religion, colonialism, communal existence itself. In the context in which he appeared, his digital manipulations seemed advanced; now, they seem everyday. But his work has only gained power with the changing times. The allure of his technique removed, the brilliance of the conception and execution remains.

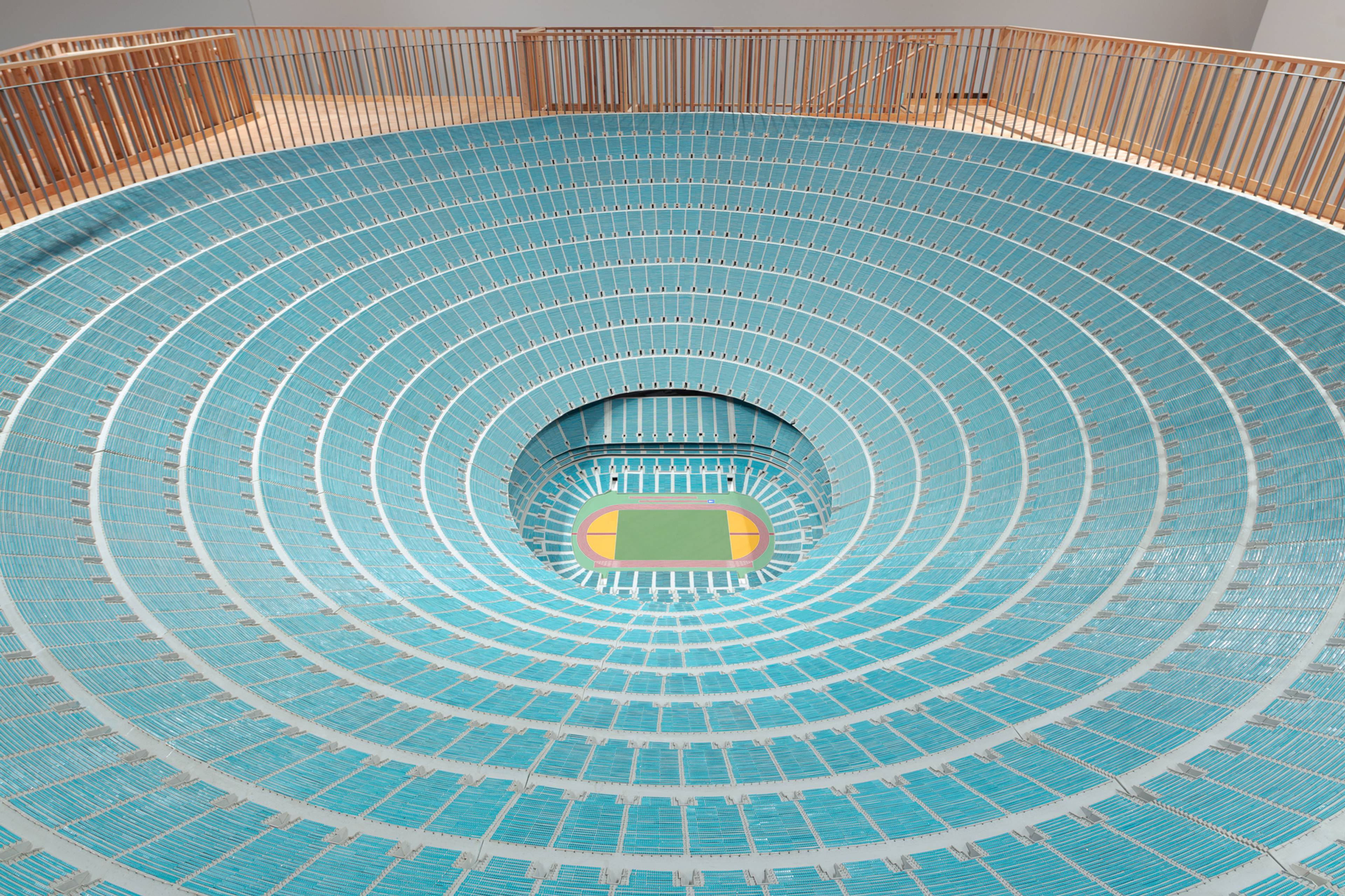

Paul Pfeiffer, Vitruvian Figure, 2008, cast resin, aluminum and acrylic, 280 x 817.9 x 812.8 cm

___

“Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom”

MOCA, Los Angeles

12 Nov 2023 – 16 June 2024