At the center of the great upstairs room of the Kestner Gesellschaft is The Dance (1988), a picture that shows Paula Rego’s husband, the artist Victor Willing, in the year of his death, dancing with another woman under a full moon. Rego (1935–2022) herself is off to the left, larger and sturdier than the other figures, dancing on her own. During their decades-long partnership, Rego – we learn in a documentary directed by her son, Nick Willing, that is shown alongside the exhibition – painfully accepted her husband’s infidelities as part of what it means to be a woman; what one has to endure in order not to be abandoned. Her art is structured around this contradiction: enduring, and continuing to endure, varying degrees of slight in life, and yet consistently manifesting those same hardships in her work as a force. A room headlined “The Triumph of the Underdog” includes Rego’s indeed triumphant “Abortion” series, made in response to a 1998 referendum to legalize abortion in her native Portugal. With faces contorted in agony, shame, fatigue, and even boredom, robust women squat over buckets or wait, bleeding, while sat on a towel on the floor. The series has the harrowing and brutally direct quality of the etchings of Goya or Blake, except intimate and deeply mundane.

But the figure of the female underdog that is evoked here is somewhat more ambivalent than is implied by the claim to her triumph. Also in this room are examples from the “Dog Women” series Rego painted in the 1990s, which, she says in the documentary, were an attempt to give something back to her late husband who had suffered from multiple sclerosis and, towards the end of his life, needed Rego to feed him. During this time, she painted him as a dog, sat on her lap. Pictured in various states of compliance and degradation, in one work crawling around on the floor, the Dog Women are ways of getting even – trading one type of humiliation for another.

View of “There and Back Again,” Kestner Gesellschaft, Hanover, 2022–23

In Rego, any commitment to justice is also, on a deeper, more compulsive level, a commitment to the balance of power. To settle a score is a complex maneuver along a two-way street: the women in her pictures are punished, and they punish each other. The Barn (1994) depicts a sadistic whipping session with two women standing atop a third, while the excellent Communion (2002) has one woman place a sacramental wafer into the obediently open mouth of another, kneeling before her, in a scene that is as much about power as about the fetishistic nature of indulging in submission. Equilibria, Rego’s paintings insist, are never peaceful, but they are unavoidable.

Everywhere in her studio (recreated in a separate but adjacent exhibition) were masks, dolls and costumes, which she used in the staging of her fantastical compositions. But amidst these grotesqueries, we find an extraordinary sense of realism. I’d even argue that, in her pictures, it is the theatrical or histrionic that allows reality to be seen at all. For like James Ensor in his famous carnival paintings, Rego employs the mask honestly – she is not an expressionist. Instead, in the myriad ways that she can twist a human figure onto a shabby couch, she shows us that the body is already an allegory, and that a mask is not an expression of alienation, but a way to cope with it.

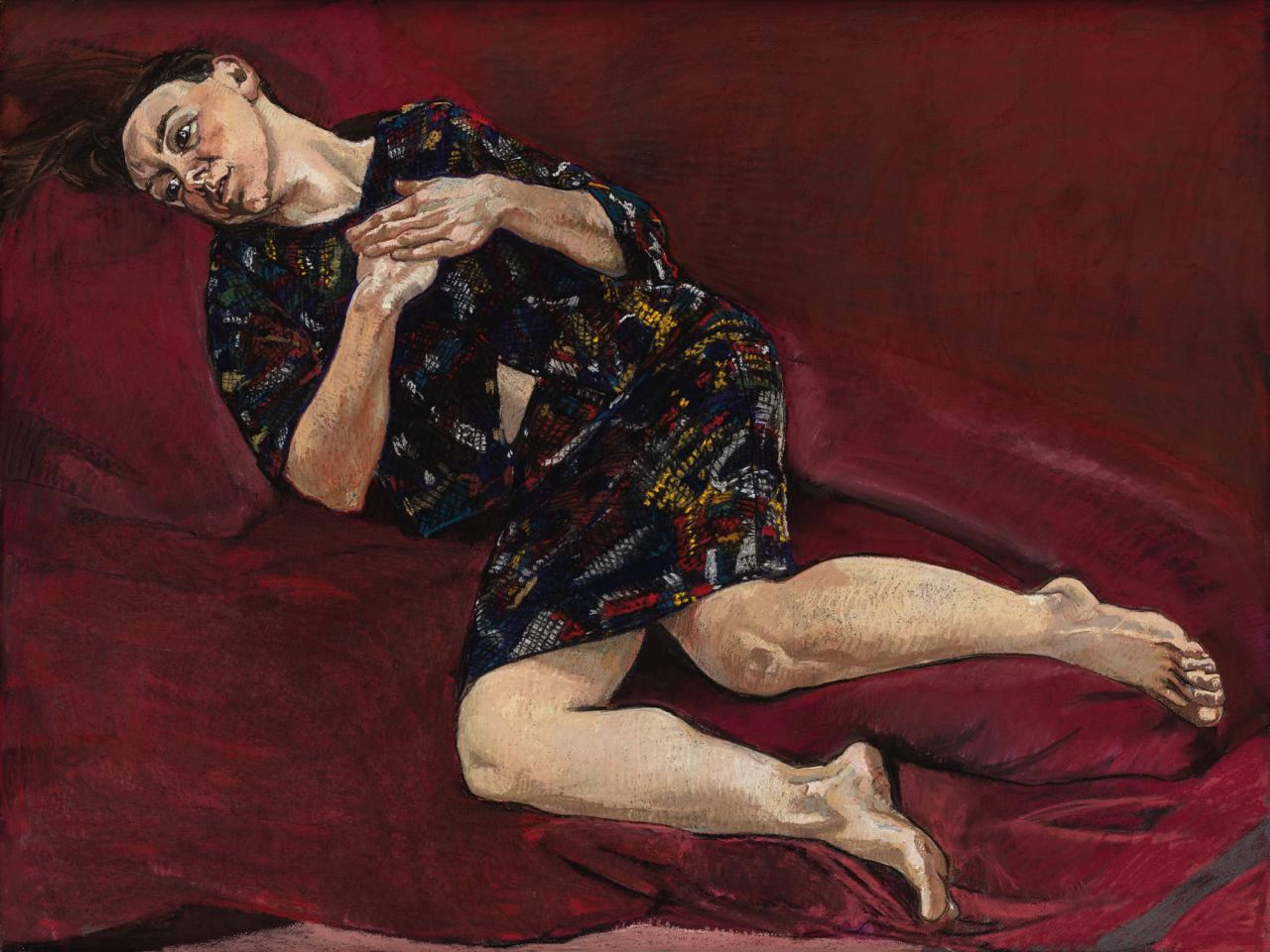

Paula Rego, Love, 1995, pastel on paper on aluminium, 120 x 160 cm

Still, Rego’s strongest game is also her most simple. In Love (1995), the blank stare of a woman sprawled across a burgundy cloth shows that the titular affect is no reward, but a state of pensiveness at best. Love is arresting and monumental, and among the best works in the show. Her muscular women lay claim to the same unflinching yet vulnerable candor as Paula Modersohn-Becker’s, albeit seen from the vantage point of more advanced age. Where Becker died at thirty-one and painted herself as pregnant before she actually was, Rego, who passed away this year in her mid-eighties, seemed to fictionalize her life in retrospect as a way to go on living it. When, in The Dance, Willing waltzes forever young in the moonlight, Rego paints her forgiveness of both him and of herself.

Even as she looks back and sees violence and oppression, her paintings offer no way to seize power without replicating those same injustices. In every single work, pain is entirely inextricable from pleasure, as force is from violence, suffering from endurance, and strength from humiliation. Her Angel (1998) – a jaw-dropping finale – carries a sponge as well as a sword; she is one who cares for as well as punishes her enemies. This is the power of Rego’s work and its tragedy.

Paula Rego, The Dance, 1988, acrylic on paper on canvas, 213.5 x 274.5 cm

Paula Rego’s studio, “Theatrum Mundi,” Kestner Gesellschaft, Hanover, 2022–23

___

“There and Back Again”

Kestner Gesellschaft, Hanover

30 Oct 2022 – 29 Jan 2023