No color is allowed into Raven Row’s retrospective of Peter Hujar (1934–87). Even those works where the photographer is the subject rather than their author are monochrome, among them four of Andy Warhol’s “Screen Tests” (1964) and a painting by Paul Thek (Portrait of Peter Hujar, 1963–64). Indeed, Hujar worked almost exclusively in black and white (the only exceptions I know of are a series that he took of Thek at work in his studio, which we might better understand as collaborations), a limitation that ultimately served to frame him not just as virtuosic photographer, but as a fastidious technician and photo-maker, too.

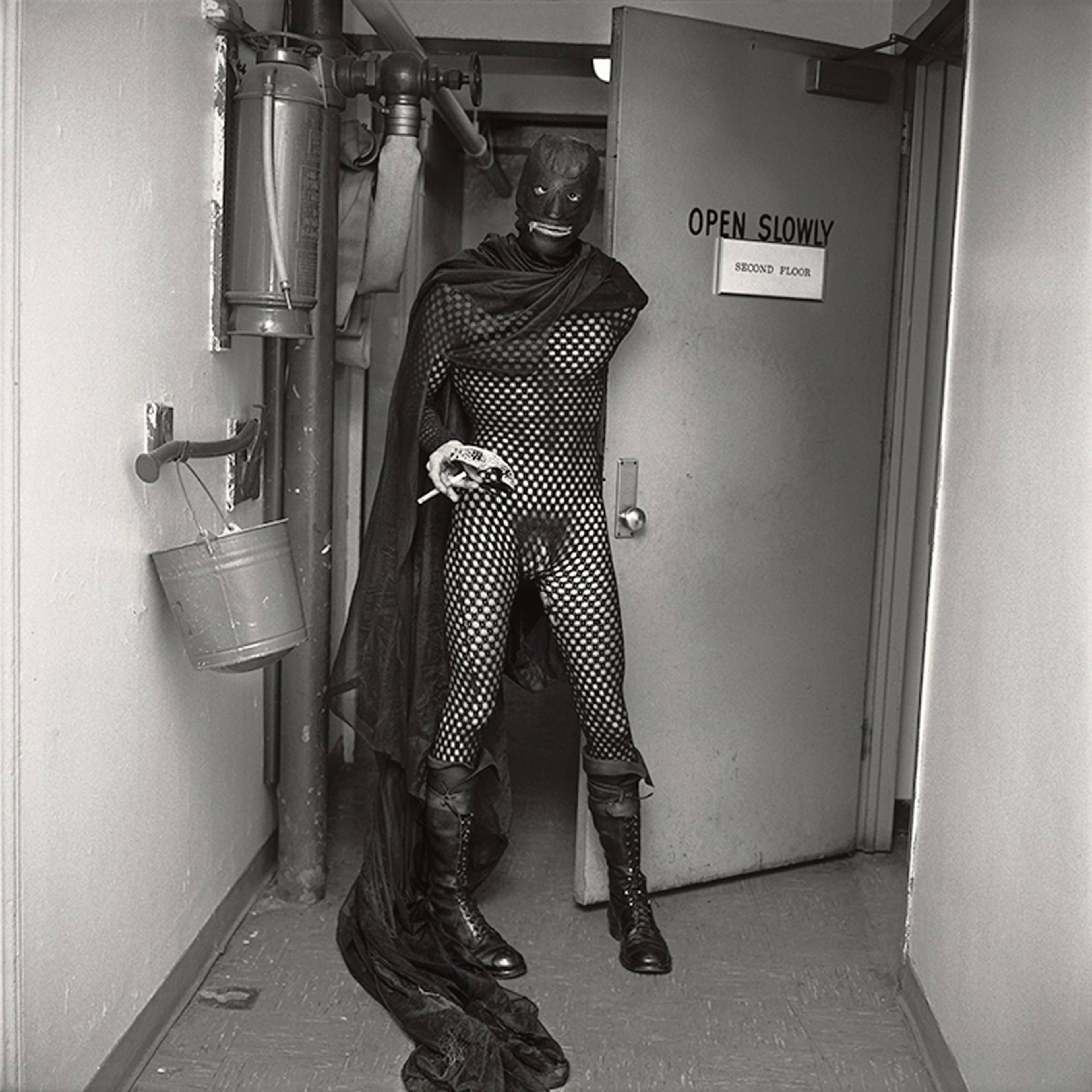

John Flowers (Backstage, Palm Casino Revue, New York), 1974

Canal Street Pier, New York (Stairs), 1983

Person in Veil (Backstage, The Life & Time of Joseph Stalin, Brooklyn Academy of Music), 1973

Knowing he built a darkroom within his Lower East Side apartment, it’s apparent that, no less than the street or the studio, his photos came together at home, with careful cropping, subtle adjustments to contrast, and hand-retouched highlights. “He believed that someday his printing would become an important aspect of his legacy as an artist,” writes Gary Schneider, a master printer whose lab produced Hujar during his lifetime and remains the exclusive maker of his new editions. “He often said that when he finally became famous, scholars would study the differences between his prints of the same image.” It’s a shame, in that light, that there aren’t multiple prints of the same image here, even if catering to an impulse to compare might ultimately detract from each singular work. That his paper of choice, Agfa Portriga Rapid 111, ceased being manufactured the year that he died, is strangely fitting for a life suddenly cut short, the possibility of posthumous mimesis cut off along with it.

In one room, the photographs are arranged in two rows across each wall – a form of display Hujar himself experimented with. In his final solo exhibition during his lifetime, at Gracie Mansion Gallery in 1986, he had arranged seventy prints in a tightly spaced frieze, positioned in vertical pairs; no photograph was placed next to an image of the same genre. “By surrounding each print exclusively with incommensurate images,” writes curator Joel Smith, “Hujar shut down the compare-and-contrast impulse.” At Raven Row, the frieze becomes a grid, hung on a freestanding wall in three rows of seven. This minor change, though, from two rows to three, quite disproportionately effects the display: The simplicity of Hujar’s original gesture undone, the desire to draw connections, this compare-and-contrast impulse, is suddenly hard to escape. One nude rhymes with another; a dead gull evokes the catacomb portrait nearby.

View of “Eyes Open In the Dark,” Raven Row, London, 2025. Photo: Marcus J Leith

There are also several series on display, including all eight photographs of the East and Hudson Rivers, created in 1976 for the chapel at Fordham University in the Bronx. Softly lit but in sharp focus, the light sparkles from each rippling surface, the absent horizon speaking to boundlessness – cityscapes without the city. A number of photographs taken on Easter Sunday, 1976 are accompanied by reproductions of the full contact sheets from the same day, demonstrating his discernment regarding which images to enlarge. This single day’s work illustrates the versatility of Hujar’s camera and his sensitivity to his environment: He captures in quick succession isolated figures on the Hudson piers (including the legendary activist Marsha P. Johnson), worshippers leaving St. Patrick’s Cathedral, city skylines, and East River vistas from the World Trade Center’s viewing deck.

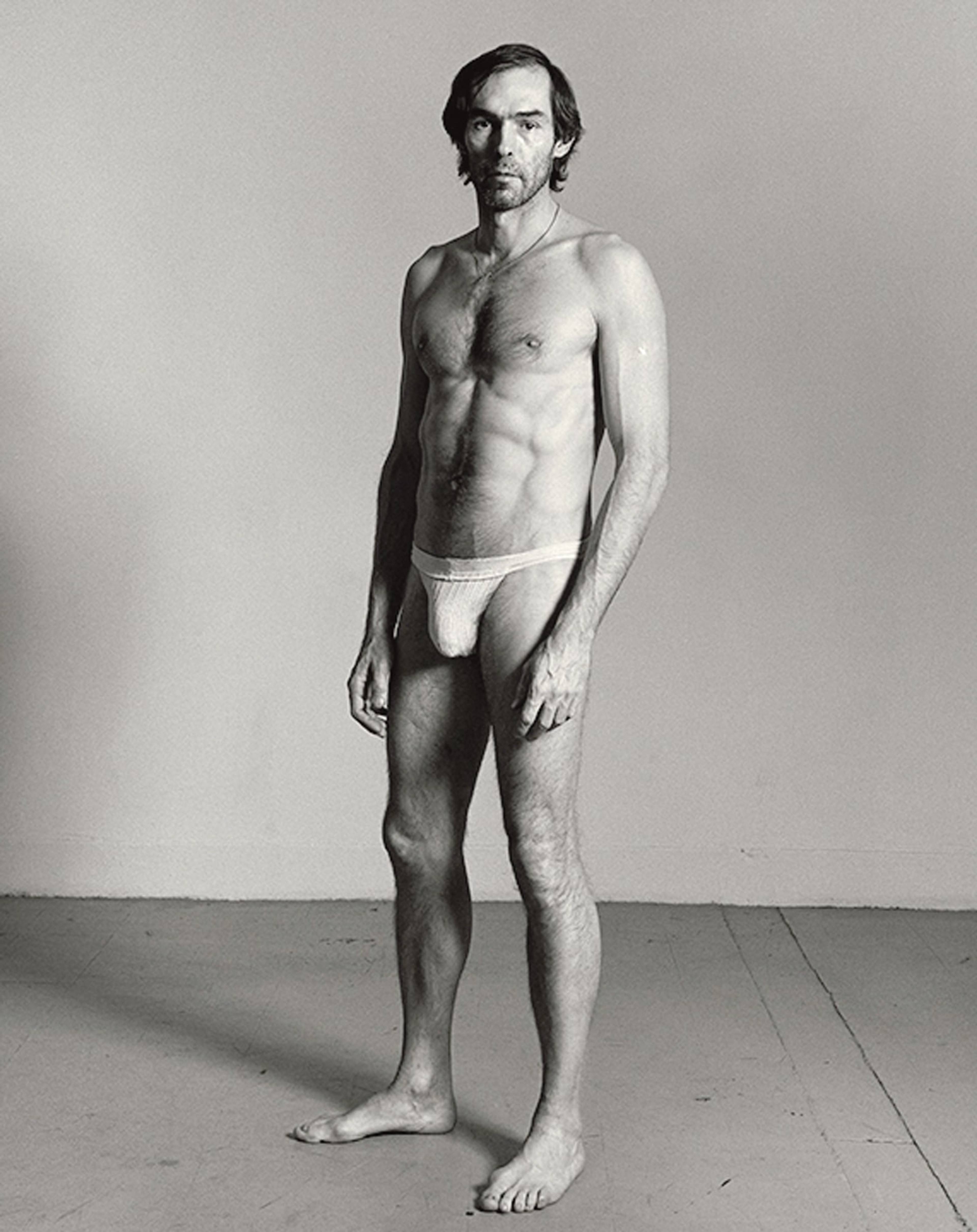

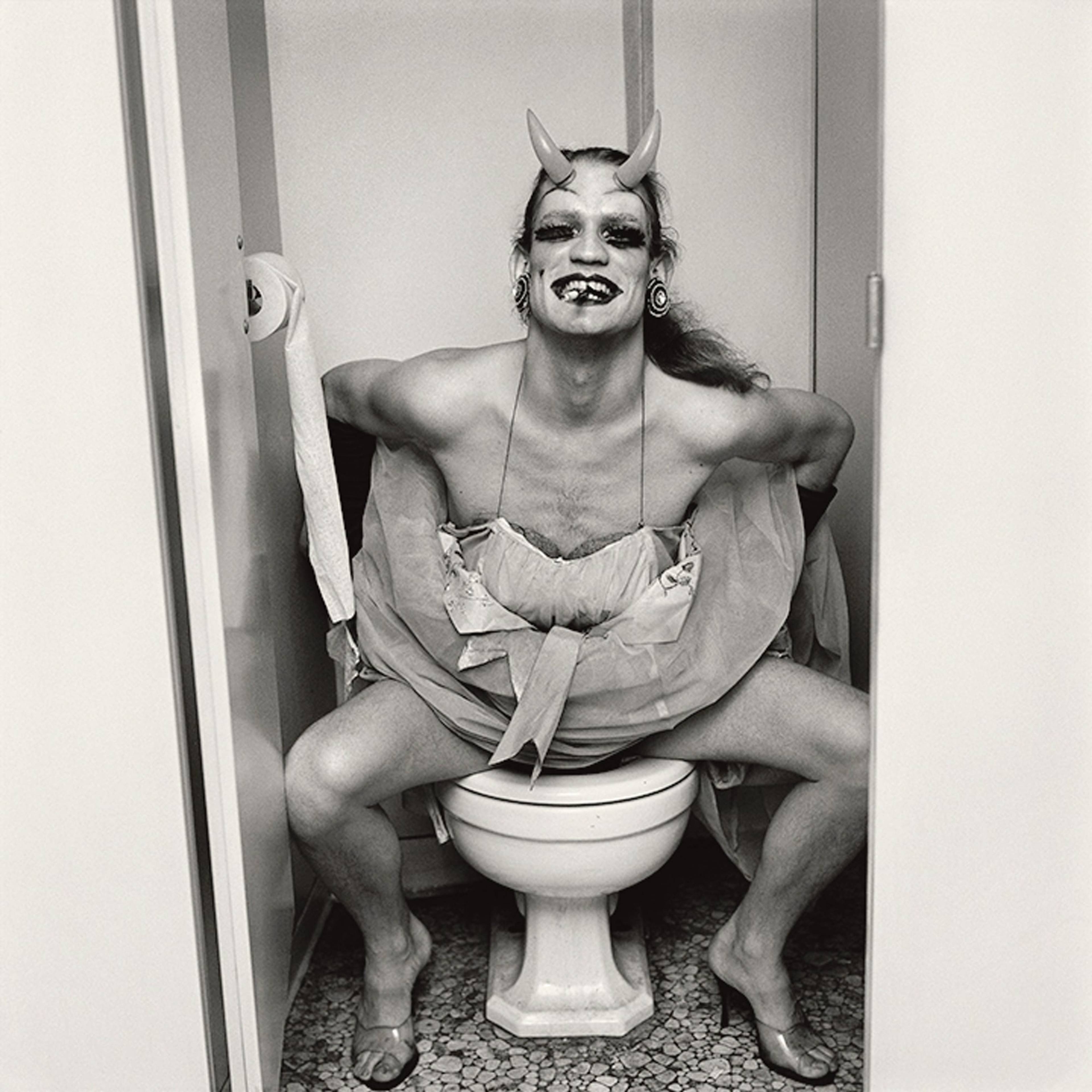

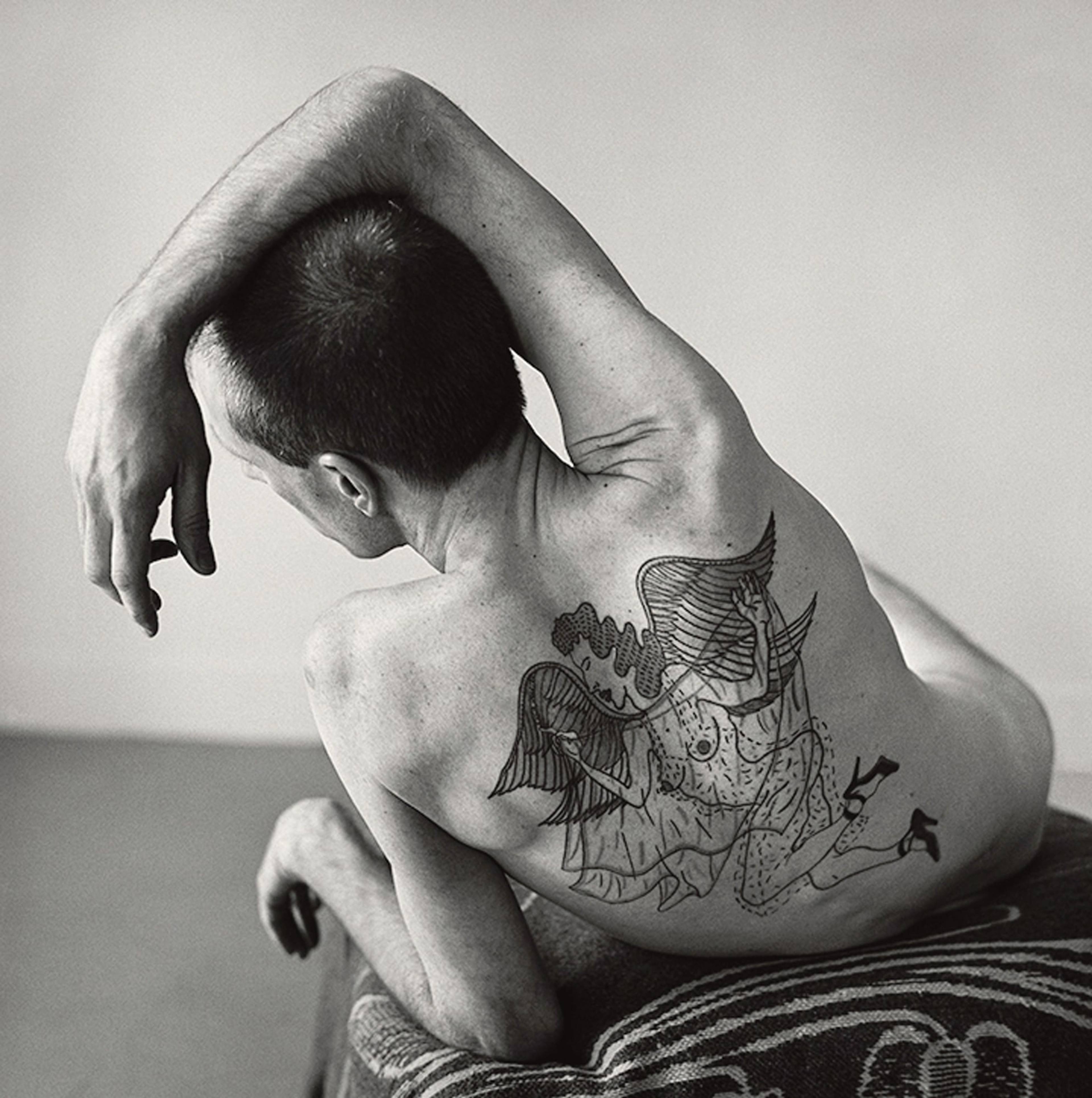

Overall, these are photographs that do not photograph well. That’s perfectly fine, perhaps even preferable, as it invites us to get close to the work, each a study in texture and contrast: of scar tissue (Torso (Pascal Imbert), 1980), the lines of an intricate back tattoo, or the fuzz of a cow’s face. Drag queens get dressed backstage, at once composed and casual. Transformation and flux – development, in the medium’s terms – are constant themes. Surface, which was more often the focus of painting criticism during Hujar’s lifetime, was evidently a fascination, from the wrinkles on an aging queen’s face (Penny, 1981) to the folds of a discarded rug. Paul Thek, Florida (1957, the earliest work in the show), meanwhile, leans alone against a mantlepiece mirror, an elegant and effective reminder of the photograph as object, not just as image.

Richie Gallo (Backstage, The Life & Times of Joseph Stalin, Brooklyn Academy of Music), 1973

White Turkey, Pennsylvania, 1985

Ethyl Eichelberger, 1981

Hujar stopped working in the darkroom after his diagnosis with AIDS, concerned that exposure to the chemicals might further compromise his immune system. After his death, writer and artist David Wojnarowicz, who counted the late photographer as a one-time lover, mentor, and friend, inherited his apartment and its darkroom, where he took up photo-making for the first time since 1980. Always heartbreaking are his photographs of Hujar moments after his death, his hand stiffening, toes swollen, a hint of medical gauze on his wrist. Counting the contact-sheet images, Wojnarowicz labelled the envelope “23 photos of Peter, 23 genes in a chromosome, Room 1423.” Three of these pictures, printed small and displayed here side by side, are at once detached, documentary, and intimate. They’re also much less sharp than those of his mentor: gray instead of saturated, and shallow where Hujar’s were intensely, sculpturally shadowed. They don’t close the exhibition, though, as one might chronologically expect, and instead coexist with Hujar’s self-portraits, his eyes still open, if now vacant.

___

“Eyes Open In the Dark”

Raven Row, London

30 Jan – 6 Apr 2025