For the past week, I have been reading two, sometimes three pornchats a day – in bed, on the bus to work, or walking to the supermarket. “Pornchat” is Polly Barton’s shorthand for the nineteen conversations about porn collected in her new book, Porn: An Oral History (2023). Not intended to be sexy, these exchanges with laypeople (like Barton herself) deal with modes of porn consumption; porn in its relationship to sex, gender, and sexuality; porn as complicit in a wider culture of misogyny; and porn as a problem of and for both representation and ethics. Above all, these chats are about – and an effort, in themselves, to work through – the difficulties of openly talking about watching sex.

Porn is tricky to address not only because it feels private, perhaps even more so than sex, but because it is essentially ambivalent. Some people, to put it clinically, “enjoy very graphic close-ups of genitals having intercourse”; others are into “getting burped on” or being eaten (!); and, as one chat participant remarks, “one of the categories is ‘grannies,’ isn’t it?” There is effectively an infinity of things that get people off and, to unfold the internet meme Rule 34, a proliferation of categories both catering and conducive to a cross-pollination of polymorphous niches – if you can think it, it’s already porn. Moreover, arousal is often intimately tied with negative affects, or, to employ Sianne Ngai’s term, “ugly feelings” like envy, shame, or disgust. Not only can our preferences clash radically, then, so that one person’s dream-porn is another’s nightmare, but the way things feel on a somatic or affective level (good or bad; or, more often, good and bad) is difficult to explain to ourselves, let alone to others. Often, we are aroused by things we find “ideologically unattractive,” as one interlocutor puts it.

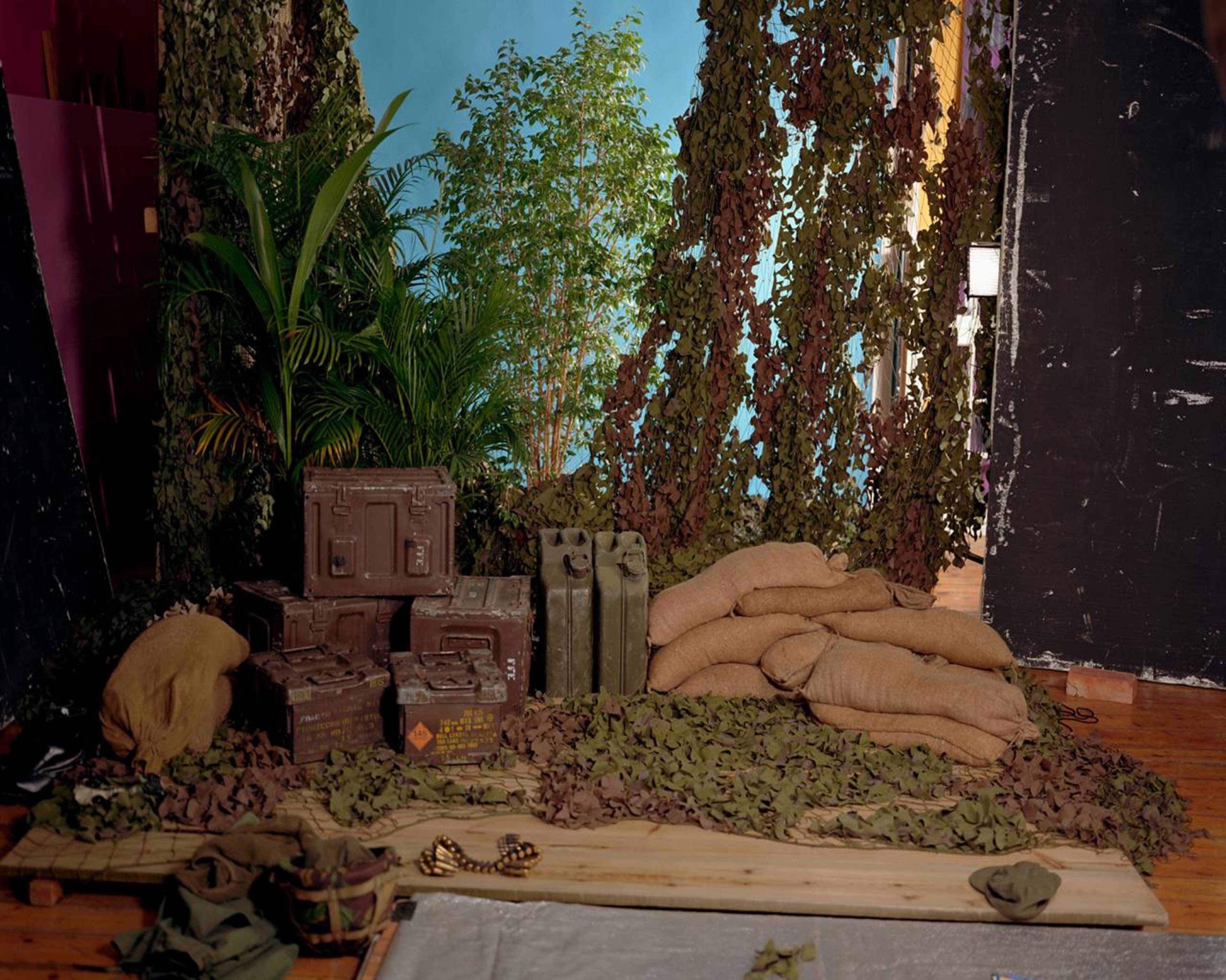

Jo Broughton, “Empty Porn Sets,” 1995–2007, C-type prints mounted on aluminum and set in sub box frames, 20.5 x 25.5 cm

The problem with porn at present is that, for many, it tends to promote precisely such “bad” visions or versions of sexuality, to the point that it now appears synonymous with images of sex that are not just distasteful, but vile or straight-up violent, making the subject all the harder to approach: “In fetish stuff, the boundaries of pain and pleasure are blurred, whereas in the mainstream pornography I’ve seen, the pain is constantly there [but] interpreted as pleasure… It’s not really identifiably S and M, is it?” observes Fifteen, a straight woman in her early thirties (here named, like all the interviewees of Porn, after the chapter in which they appear). That not all porn can be read as such is something that a number of the book’s narrators point out. Indeed, though readily available and arguably centered on mainstream platforms, this violent kind of material likely forms a small percentage of all available pornographies, due in no small part to porn’s democratization and amateurization on platforms like Pornhub or the “user-generated, human-curated” site MakeLoveNotPorn. A burgeoning number of queer and feminist pornographers notably work not just to make porn’s production more ethical, but to actively challenge mainstream tropes, reimagining pleasure beyond the dominant male economy and for a range of diverse and historically illegible subjects. Still, questions of the ethics and political correctness of porn remain open, for women more so than for men (who can afford not to ask) and for queer communities and individuals (who are somewhat ahead of the game, partly because thinking sex in queer circles has been less impeded by the historical perspective of anti-porn feminisms). To borrow from American artist and pro-sex feminist Betty Dodson, it feels as though “women are still debating what is acceptable to make, view, or enjoy. The porn wars rage on while most guys secretly beat off to whatever turns them on.”

Indeed, what makes Barton’s book at once inviting and difficult to think with is her sensitive awareness of her own mixed feelings vis-à-vis porn, which, in part, are anchored in the fear of sexing and committing to partners whose porn consumption might be unethical, or mismatched with who we know them to be, both in sex and outside of it: “If you found out that [your] partner was watching rape porn in his workspace, would that affect you?”

I trust you not to break me the way the world does, and you trust me to take care of you in return.

So much hinges, here, on the place afforded to fantasy and on our capacity to separate the latter from reality. “What is the difference between a newspaper account of a rape and a fictional account of rape; a porno account of a rape and our fantasy about a rape?” is one among many questions raised by the 1982 Barnard Conference on Sexuality, a key event in the feminist sex wars of the 1980s, that remain unresolved. What I can say is: Though in itself profoundly ambivalent, porn lacks what makes sex gratifying, distinctly pleasurable, and even scary – what cultural theorist Lauren Berlant describes as “the awkwardness of intense proximity,” and which arises not just from laboring to get our individual rhythms and bodies to meet, but from opening oneself up to the possibility of things going terribly wrong. Sex, to stay with Berlant, is more often an episode, an uncertain encounter that necessitates a kind of dance or negotiation – I trust you not to break me the way the world does, and you trust me to take care of you in return. Sex demands that we enter into the situation, that we experiment in and with relation, in a way porn does not.

This, in part, explains the position, encountered in Porn, that one can enjoy certain things onscreen that one wouldn’t necessarily want to try out physically, either because they seem impossible to achieve, or feel somehow “wrong” to demand of the person(s) with whom we share in the ambivalence of a wanted co-presence. Mainstream porn tends to offer skewed images of sexual pleasure that privilege, among other things, male gratification, hegemonically attractive bodies, and uninterrupted flows of desire that always reach orgasm (the “money shot”), messing with our intimacy antennae and making the prospect of a shared middle both less attractive and more difficult to locate and actualize. Jean Baudrillard’s observation from 1979 is no less analytically germane today: “Pornography says: there must be good sex somewhere, for I am its caricature.”

Jo Broughton, “Empty Porn Sets,” 1995–2007, C-type prints mounted on aluminum and set in sub box frames, 20.5 x 25.5 cm

“What would sex look like if porn didn’t exist, and we didn’t have this projection or representation of sex? If it was just guided purely by our bodies and blank minds?” Seven asks. Like my teacher in these matters, pioneering sex thinker and activist Gayle Rubin, I am skeptical of the idea that porn, in its totality, is morally degrading or what’s responsible for violence against women. Not only is this view fraught with all kinds of intentional fallacies, it also diffuses queer and feminist pornographies’ potential to destabilize and subvert hegemonic constructions of gender, sexuality, and pleasure. At the same time, I am skeptical of the notion and practice of an unchecked sex positivity that would content itself with dismissing everything that is harmful as pure fantasy, as if the autonomy of the latter could be guaranteed, its field somehow surgically separated from reality. I, like Eight, “do think people have responsibility towards their desires, at least sometimes.” If your thing is “Keep It in the Family,” maybe that should be interrogated, you know?

My unwillingness to let fantasy rest also stems from my conviction that, like silence around sex and porn, the sense that fantasy is an individual right, a square of private property to be protected, is not natural, but cultivated, the byproduct of a culture where the soul of the individual, her productive forces so exhausted by capital, must finally seek (simulated) revenge somewhere. To paraphrase Michel Foucault, we must not think that saying yes to sexual fantasy means saying no to power. There are no pure desires or fancies to exempt from the table of social or political critique.

Jo Broughton, “Empty Porn Sets,” 1995–2007, C-type prints mounted on aluminum and set in sub box frames, 20.5 x 25.5 cm

Still, querying fantasy need not shame, police, or “correct” kink, which would entail presupposing a natural (and “loving”) ideal of sexuality, as is often the case with anti-porn campaigns. It can, more optimistically, be about asking what else we can do with it. One of the promises of mutual-consent BDSM practices, and of feminist and queer porn more widely, lies in their opening up of spaces for experimenting with fantasy and power differentials in situations that feel mutual, starting out with a regard for participants’ safety and agency. Such play, I think, can travel across sex and toward a transformational, world-building politics.

Ultimately, as with sex, the question to be asked of porn is not how to free it, but: “Who will manage it, and what will we ask of it […] would it be possible to think about it […] as material for new forms of life?” There are certainly people out there, as in Barton’s book, for whom porn does enable experiments in revolutionary sex and sociality. For those of us less brave, pornchats may well be how we begin “to make sense of what is being sensed,” how we work towards different distributions of the sensible, and how we get to that place where good sex is.

Jo Broughton, “Empty Porn Sets,” 1995–2007, C-type prints mounted on aluminum and set in sub box frames, 20.5 x 25.5 cm

___