“Post Human” is not quite a sequel to the exhibition of the same name that opened in 1992. More like an addendum. Where the original traveled over the course of a year to five museums between Lausanne and Jerusalem, this one seems destined only for a stay at a commercial gallery in Los Angeles, whose namesake organized both.

Including work by many now-canonical artists of the 80s and 90s, the earlier “Post Human” presented a survey of the “new artistic interest in the body and in the presentation of the self,” much of it constituting a kind of hysterical figuration (distorting, fracturing, and rescaling the human form), or else addressing human surrogates and enhancements (cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, clothing, and consumerism). Some of those same artists – Cindy Sherman, Charles Ray, Matthew Barney – feature in the current iteration, in some cases with the very same works, notably Paul McCarthy’s Garden (1991–92), a large, Disneyland-style forest tableau with animatronic father and son fucking a tree and a mound of dirt, respectively. Joining these is a selection of work by a younger generation – Josh Kline, Alex Da Corte, Jamian Juliano-Villani – which we are encouraged to see as extending the anxious and ecstatic efforts of their artistic forebears. While the intent of revisiting this exhibition is surely to make a claim for its enduring influence, it also inevitably raises the question of change. How far have we come?

Jordan Wolfson, Untitled, 2016, inkjet print and adhesive media on aluminum, 208 x 175 x 63 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Pace Gallery. Photo: Peter Clough and Robyn Lehr Caspare

Ivana Bašić, I will lull and rock my ailing light in my marble arms #2, 2017, Wax, glass, breath, weight, pressure, stainless steel, oil paint, silk, cushioning and marble dust, 320.04 x 314.96 x 38.1 cm. Courtesy: the artist

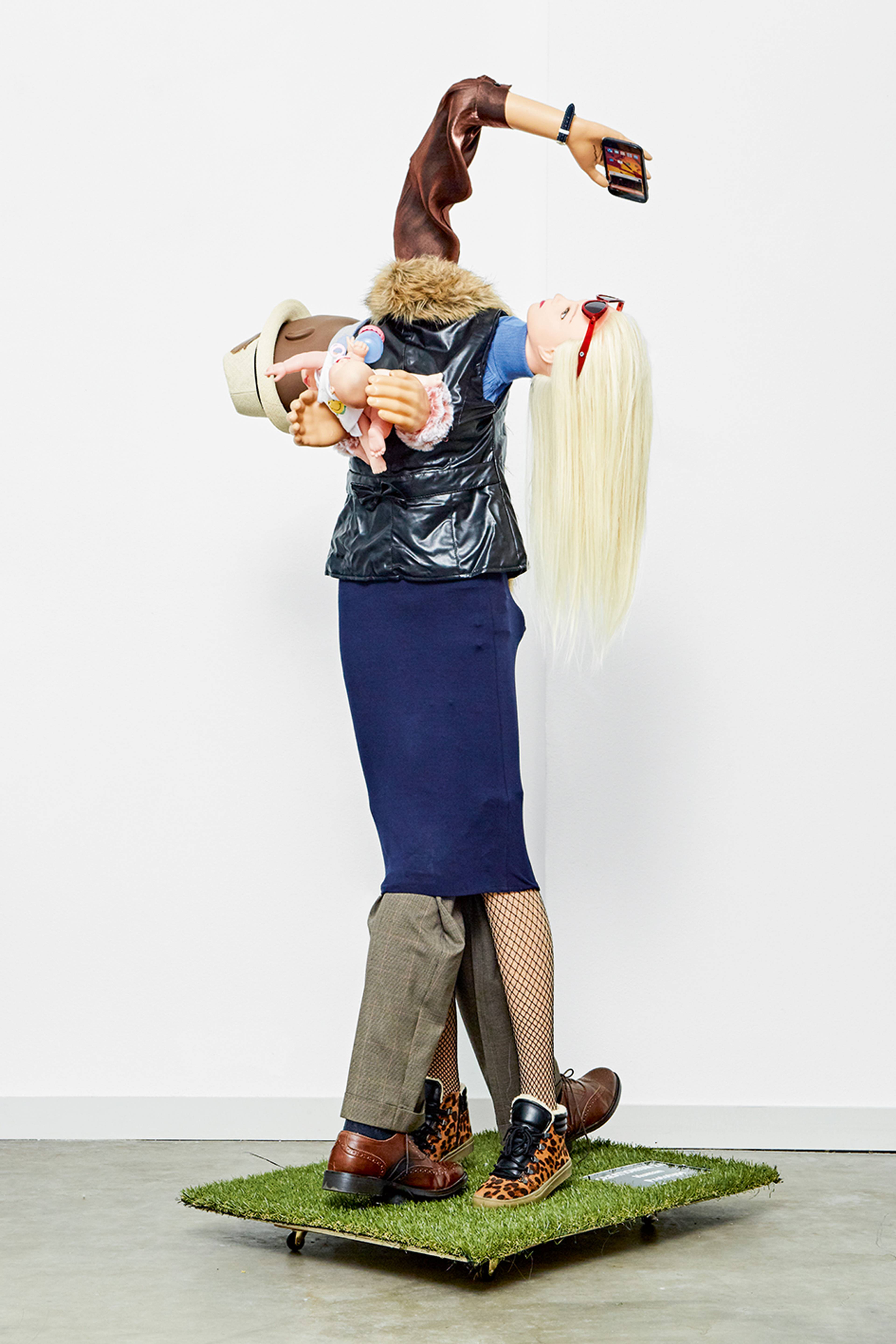

Pippa Garner, Human Prototype, 2020, mixed media, 198 x 84 x 91 cm. Courtesy: the artist and STARS, Los Angeles. Photo: Bennet Perez

Kiki Smith, Dark Water, 2023, bronze, 183 x 165 x 71 cm. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: Dan Bradica

There are, of course, qualities that distinguish the newer art from the old. A sci-fi sensibility that characterizes some of the recent work – for example, Ivana Bašić’s sculpture I will lull and rock my ailing light in my marble arms (2017), which looks like an HR Giger baby monster – offers a more fantastical vision of the transfiguration of the body. Obviously, new tools and materials have since become available: scanners, 3D printers, polylactic acid. Whatever else they may be, works like Frank Benson’s Human Statue (Jessie) (2011), a meticulously rendered bronze sculpture made through precise scanning and 3D modeling, or Chris Cunningham’s Transforma (2024), a video of a plastic blonde with a festering, distending, and mutating mouth, are testaments to technical progress. On the other hand, you could easily imagine Alex Da Corte’s Well for Sensitive Boys (2022), a pastel-painted sculpture in the simplified language of the stage or theme park, beside a Koons or a McCarthy in the 1992 catalog. More than just the occasional resemblance, however, the overwhelming impression given by this grouping of old and new is one of congruity. There appears a constancy of aesthetic and conceptual concerns between 1992 and 2024 that one can’t help comparing with the vast changes in art between 1960 and 1992. Partly, we are set up to see things this way – the choice of artists gives a sense of kinship, or perhaps of a software update – and you wonder what a different selection might have done. Not that I was exactly hungry for more, and maybe it wouldn’t have made a difference, but as far as I could tell, only one work involves AI (Pierre Huyghe’s Idiom, 2024, a featureless golden mask generating some hardly audible speech). More striking is the inclusion here of painting, totally absent from the original and perhaps unimaginable in a vanguardish exhibition in the 90s. But the recuperation of painting is hardly an art-historical watershed; rather, it only adds to the impression of stasis, qualified on the shifting sands of taste.

Views of “Post Human,” Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles, 2024

Photos: Joshua White | JW Pictures

In his catalog essay from 1992, Deitch lays out an elated, McLuhanesque vision of a dawning post-human future. With a ripped-from-the-headlines survey of technological and social transformations underway – plastic surgery, biotech, computer networks, dieting – he speculates about the plasticity of the body and subjectivity, as well as art’s capacity to register these changes. Today, we live in a far more post-human world – with our Instagram filters, gene editing, and gender confirmations – as well as a grotesquely dehumanized one. Yet the most significant developments in art this century have to do with the market and an increasing openness to exhibiting and buying work by members of previously excluded groups. Both are consequential, and both are reflections of historical transformations external to art – one socioeconomic, the other sociopolitical. The new “Post Human” might have had as a subtitle “Post Historical,” intended as it seems to demonstrate how the counterpoint between art history and broader historical change has since fallen out of sync. In its place, we have a set of apparently incommensurate temporalities: relentless technological change, slowly encroaching planetary collapse, and art’s horizonless contemporary.

Josh Kline, MAOI Inhibitors Can’t Fix This (Elizabeth / Administrative Assistant), 2016, 3D-printed plaster, ink-jet ink, and cyanoacrylate, foam and polyethylene bag, 58.4 x 71.1 x 99.1 cm. Courtesy: the artist and 47 Canal, New York. Photo: Charles White / JW Pictures.

___

“Post Human”

Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles

12 Sep 2024 – 18 Jan 2025