Croissants and coffee and a silvery ocean view only interfered with by some Alexander Calder garden sculptures: This is what’s served to the right of my seat in the shamelessly gorgeous café at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. At left, Maria Alyokhina, a founding member of Pussy Riot, is serving a fair amount of lenience answering an audience question about whether everyone can actually be Pussy Riot – as a wall in the museum’s adjoining retrospective exclaims. Is it possible to go be an unbending activist in your everyday life as (presumably) a pleasant Scandinavian art professional? “We were born under different conditions,” Aloykhina replies matter-of-factly, her restrained impatience confirmed by the delicious surroundings. “But this is not a reason not to riot.”

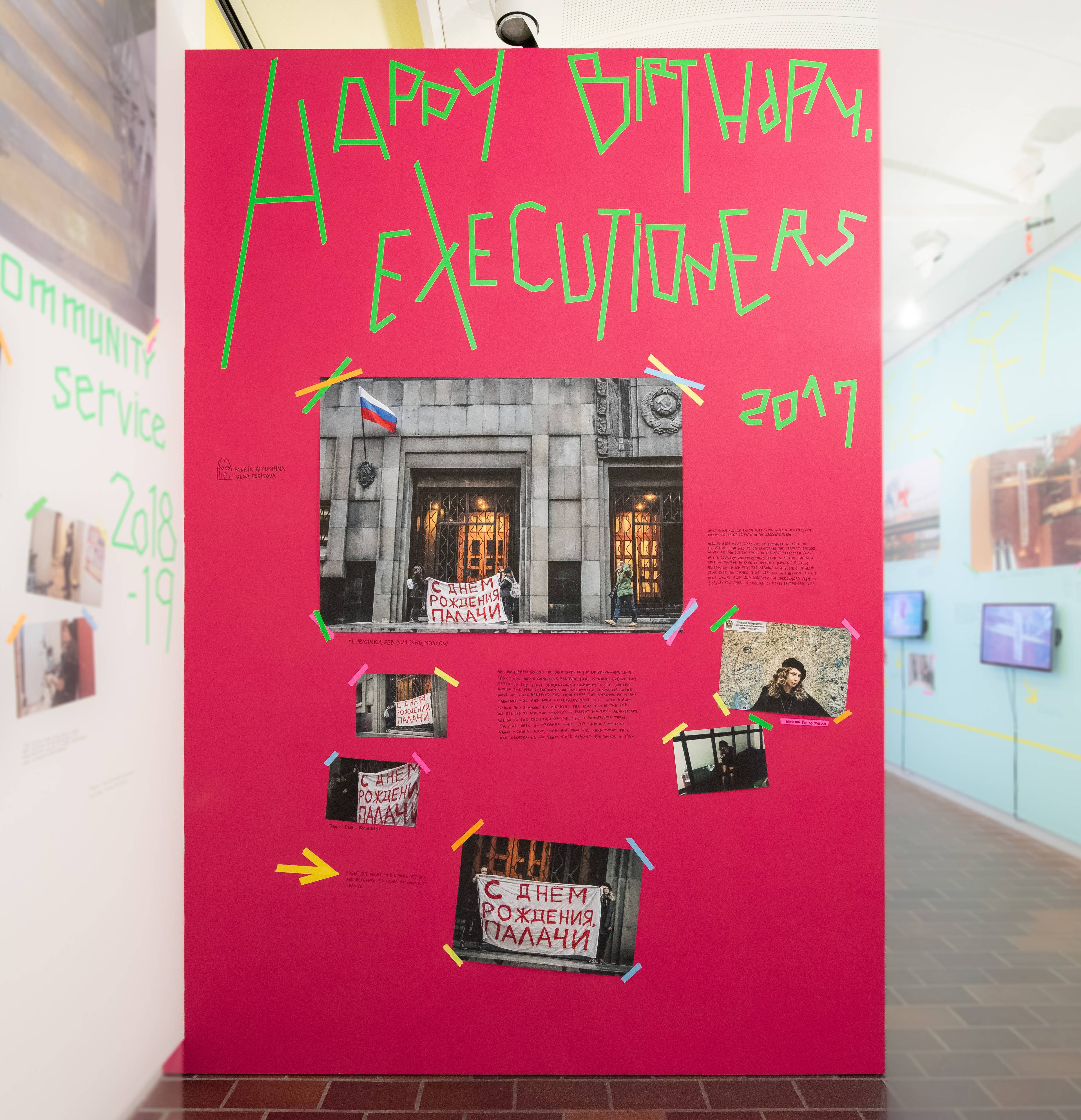

Continuing and expanding the 2022 exhibition “Velvet Terrorism” at the Reykjavik artist-run space Kling & Bang, Louisiana invited the Russian collective to take over a museum wing. One might forgive the slight cringe of the institution’s efforts to manufacture punk’s vibe: Never had an image hung crooked on these walls, never had they been covered in scruffy handwriting, and suddenly the exhibition space is nothing but tape and felt-tip pen from floor to ceiling. What looks like punk in quotation marks, though, quickly disappears behind the actual content: Pussy Riot’s extraordinary acts of resistance.

View of “Velvet Terrorism,” Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, 2023. Courtesy: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Kim Hansen

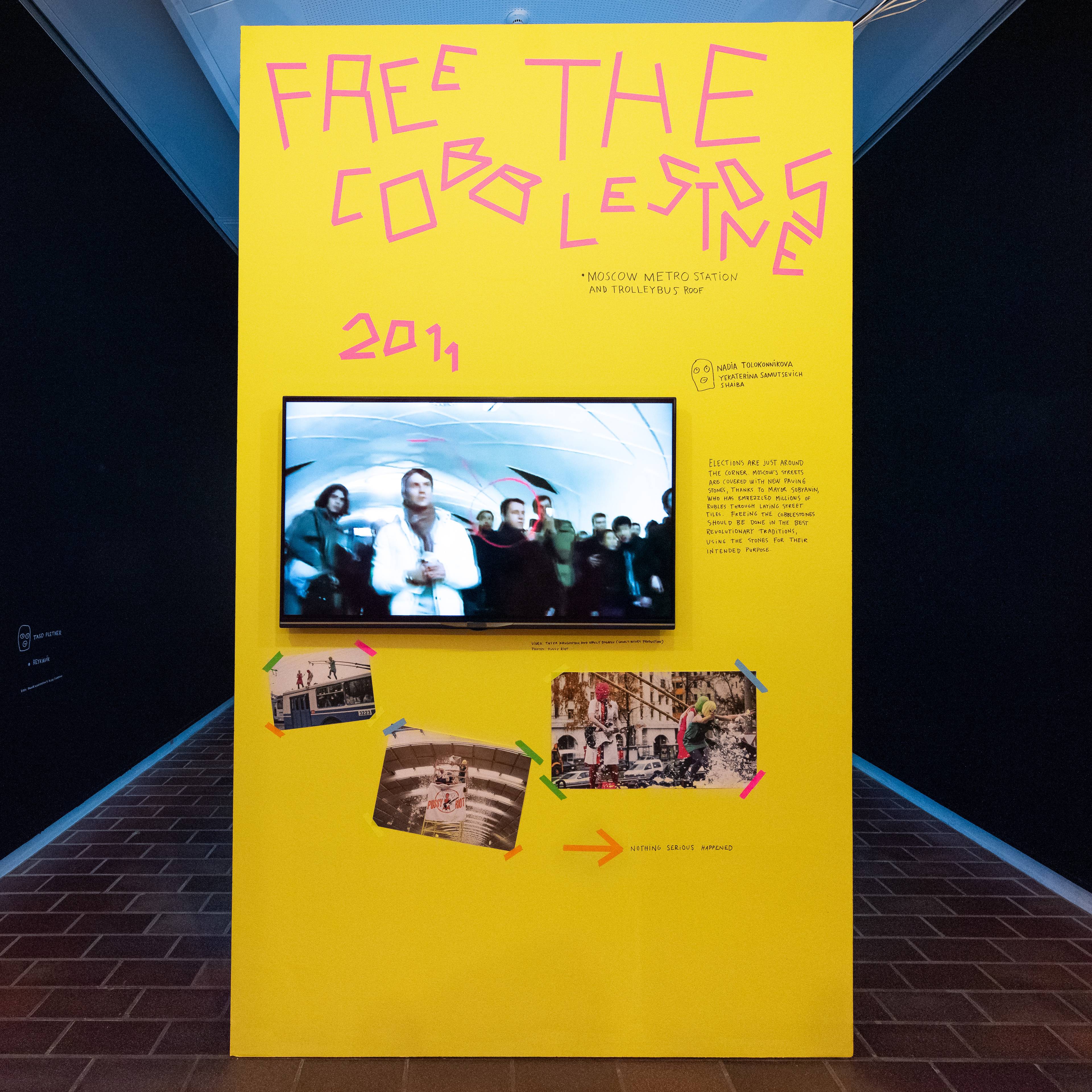

Needless to say, their legacy is monumental. Since 2011, Pussy Riot has taken it to squares and churches, to a World Cup football pitch, to bus roofs and metro stations and prisons. “Velvet Terrorism” is a chronological show and also a dashing chaos. It is an insisting disarray of sound from many headset- less screens, melting songs and protests and interviews and arrestments into a frantic pool of protest. It is an explosion of imagery on life and art under constant suppression, of the immanent, urgent misogyny strangulating a nation by presidential or godly decree. And it is an encyclopedia of text that is as demanding as it is worth the time to read carefully. It’s a relief that Pussy Riot has poured in so many words, because it quickly dawns on you that your own are insufficient. “Riot,” as only those who know could put it, is always a thing of beauty.”

The chronology begins just around Vladimir Putin’s 2012 election to a third presidential term and the catastrophic prospect of his open-ended rule. “We dreamed of a different history because the one in which the president turned into an emperor was not the one we desired,” it reads next to a video of eight people in flashy-colored dresses and the collective’s signature balaclavas. Armed with guitars, a smoke bomb, and the fist-adorned feminist flag they mount Lobnoye Mesto, a stone platform on Red Square, and scream about how “the bitches are pissing themselves behind the red walls” abolishing the patriarchy whose perpetrators “will beg the feminist wedge for mercy.” A quiver is inevitable.

Views of “Velvet Terrorism”

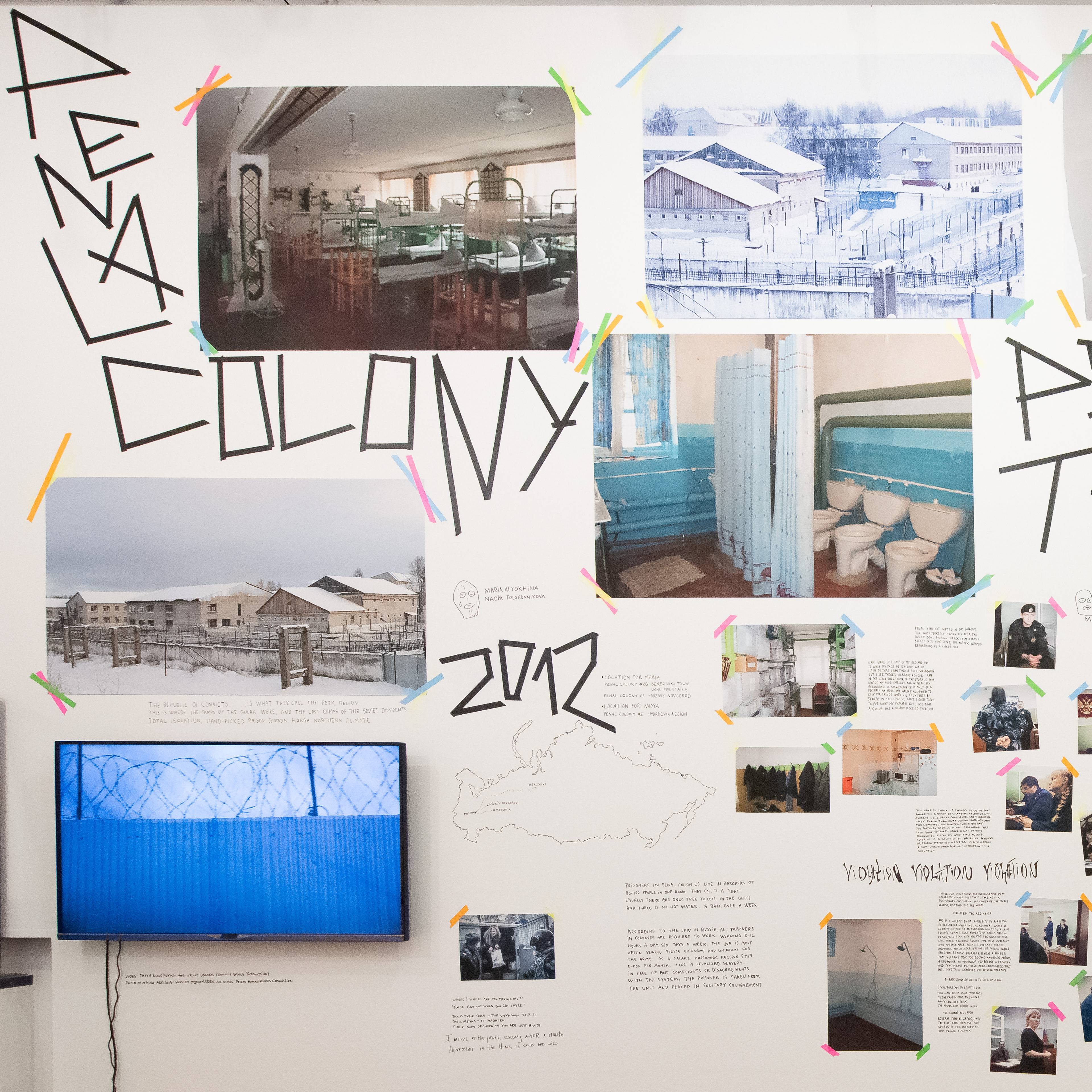

Several iconic and brutally backlashed actions follow. Likely their most widely known intervention, Punk Prayer (2012), takes place in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, where five balaclava-clads “serve punk prayer at the altar because women cannot approach it.” Amid roaring punk, a choir of mournful female voices invoke the Virgin Mary to drive away Putin and become a feminist; Maria Alyokhina and Nadya Tolokonnikova were subsequently arrested and sent to prison for this act of so-called “hooliganism.” The walls plastered with footage from inside a variety of detainment facilities should make apparent to even the most cloudheaded museum-goer that revolt autospells confinement. Still, it is a painful shock to realize that a formerly imprisoned woman is standing right in front of you, listening to the national anthem that was Alyokhina daily alarm in jail.

In all its simplicity, it is an exhibition of personal witness. While much documentation of and info about Pussy Riot’s actions is accessible online – and global media is thick with supportive coverage of their epic deeds – their own testimony to twelve years of violence, claustrophobically encased in phone snapshots and handwritten notes, is not, and it is these ephemera that exude their rage and pain. What must follow, though, is a rather shameful acknowledgment that this compassion, expressed as Instagram stories drenched in emoji fists, flames, and broken hearts, amounts to nothing. We can try to understand that this horror concerns us, or to concern ourselves with this horror; the reality, however, is that we are likely to fail.

We can look at the faces of resistance: glass-caged in court, handcuffed in police custody, violently removed from public spaces. Yet their expressions remain open and never not superior to repressive power, elevated on another’s behalf, which is perhaps the essence of courage. Though our language and emotion will fall short, what we need, is to look, at the horror show, the limitless heartbreak, and the exclamation point: Riot is always a thing of beauty.

View of “Velvet Terrorism”

Still from Pussy Riot, Punk Prayer, 2012, 86 min. Photo: Mitya Aleshkovsky

___

“Velvet Terrorism”

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk

13 Sep 2023 – 14 Jan 2024