Disturbing as it may be, we live amid a resurgence of “authoritarian characters,” or figures inclined toward subservience, from right-wing populists to libertarian techno gurus. Against these trends, the four standalone exhibitions of Steirischer Herbst 2023, catchily – if questionably – entitled “Human and Demons,” surface the complexities of a fascistizing social landscape by appealing to “minor” personae intricately woven into the history of Graz, whose archival materials and images become starting points for observing installations and more ephemeral artworks around the city.

The musical archive of Dietrich Schulz-Köhn, a Luftwaffe officer who pseudonymously published an underground jazz magazine during World War II and subsequently founded the city’s International Society for Jazz Research, embarks visitors to a defunct, dimly lit call center on an auditory journey in “Demon Radio.” An undocumented visit to Graz by the artist Mira Schendel, who was designated as Jewish by Mussolini’s regime and stripped of her Italian citizenship, is reimagined with AI at the Minoritenzentrum’s “Church of Ruined Modernity” to unsettle the 20th century’s plastics heritage. The anti-relativistic physicist Stefan Marino, whose suicide at the University of Graz followed his disproof of a theory of free energy, guides visitors to Forum Stadtpark through a para-scientific presentation, “Villa Perpetuum Mobile,” populated by levitating and kinetic machines. Lastly, an ex-supermarket is transformed into “Submarine Frieda,” an immersive, subaqueous space inspired by a pacifism-encrypted postcard from the 1920s.

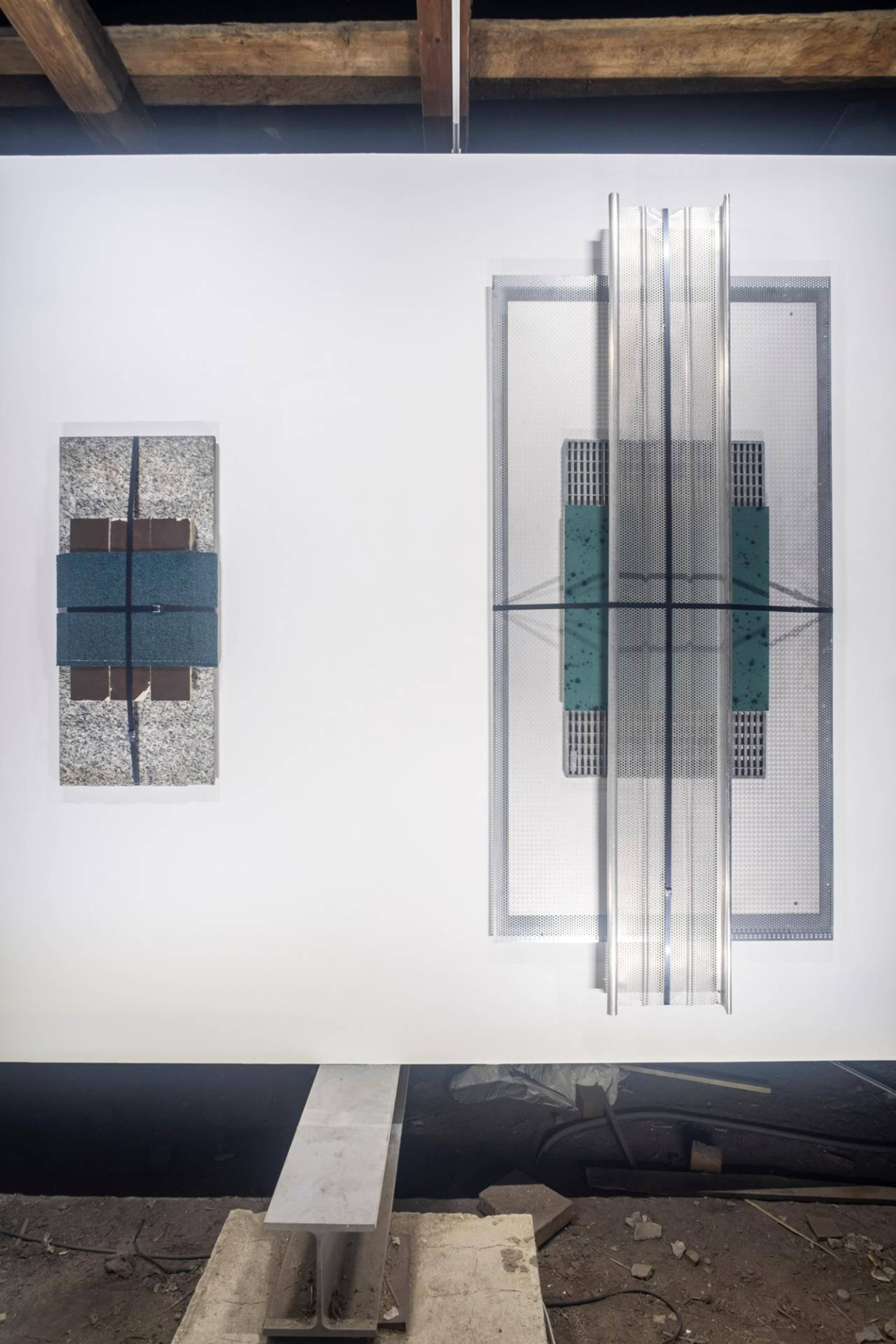

Andreas Fogarasi, Nine Buildings, Stripped (Vorklinik), 2023. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: Steirischer Herbst / Mathias Völzke

Among several artists probing the symbolic power of totalitarian sculpture and (post)modernist buildings, Dana Kavelina’s macabre puppet animation Lemberg Machine (2023), installed in the Minoritenzentrum’s dusty attic, stands out. Made in the Czech surrealist tradition, this multilingual work begins with a short-lived monument in Lviv dedicated in 1939 to Stalin’s pseudo-democratic constitution, its figures coming to life and arguing in Ukrainian, Polish, Yiddish, and Russian. Representing the imperialist concept of the “friendship of peoples,” this “slap in the face monument,” as the voiceover describes it, subsequently sheds light on that city’s histories of repression and genocide.

The assemblages of Andreas Fogarasi’s Nine Buildings, Stripped (2023) and Meg Stuart’s dance video Shelf Life (2023) thematize the disappearance of a former medical faculty’s behemoth architecture. Fogarasi repurposes surviving components of the Vorklinik’s design, incorporating them into Tatlin-esque counter-reliefs bondaged as if to tame modernist demons. Stuart, meanwhile, uses the building as a dance partner, interacting with its foldable and movable parts: doors, chairs, blackboards, and rotating stands used for demonstrating cadavers. Her work takes a dialectical twist, initially portraying the critically fetishized functionality of modernist architecture as authoritarian and inhuman, only for the intimacy of the dancers to restore its democratic promise.

Still from Dana Kavelina, The Lemberg Machine, 2023, video, c. 53 min. Courtesy: the artist

Still from Meg Stuart, Shelf Life, 2023, video, 24 min. Courtesy: the artist

Adjacent the Schlossberg’s clock tower, Lulu Obermayer’s performance Agoraphobia (2023) drew attention to a proto-fascist monument from 1932 by Wilhelm Gösser, an ideologically omnivorous local sculptor. Two singers and a boys’ choir sang excerpts about male tears from German, Austrian, and Italian operas, before the figure was “shot” with a water gun and offered a handkerchief. Appealing to a more fragile masculinity, it roused compassion for a figure who, carved in stone, must endlessly perform one outdated gender role in a rapidly changing society.

The master-like authority of speech, hypothesized by the psychoanalyst Mladen Dolar as stemming from the proximity of listening and obedience in many etymologies, is crucial to works by Zuleikha Chaudhari, Dani Gal, Adrienn Hód, and Anton Kats. In Chaudhari’s video installation Rehearsing Azaad Hind Radio (2018), actors portray Subhash Chandra Bose, a leader of Indian decolonization monumentalized in New Delhi last year. The script, based partially on Bose’s fervent radio propaganda and the actors’ own commentaries, presents him as an open advocate of violence who collaborated with Nazi Germany and imperialist Japan. Installed behind the glass of a vocal booth, the projection screen remains inaccessible, while a dark reflection imbricates viewers as scripters and broadcasters of history.

Zuleikha Chaudhari, Rehearsing Azaad Hind Radio, 2018, installation, video, 40 min. Courtesy: the artist

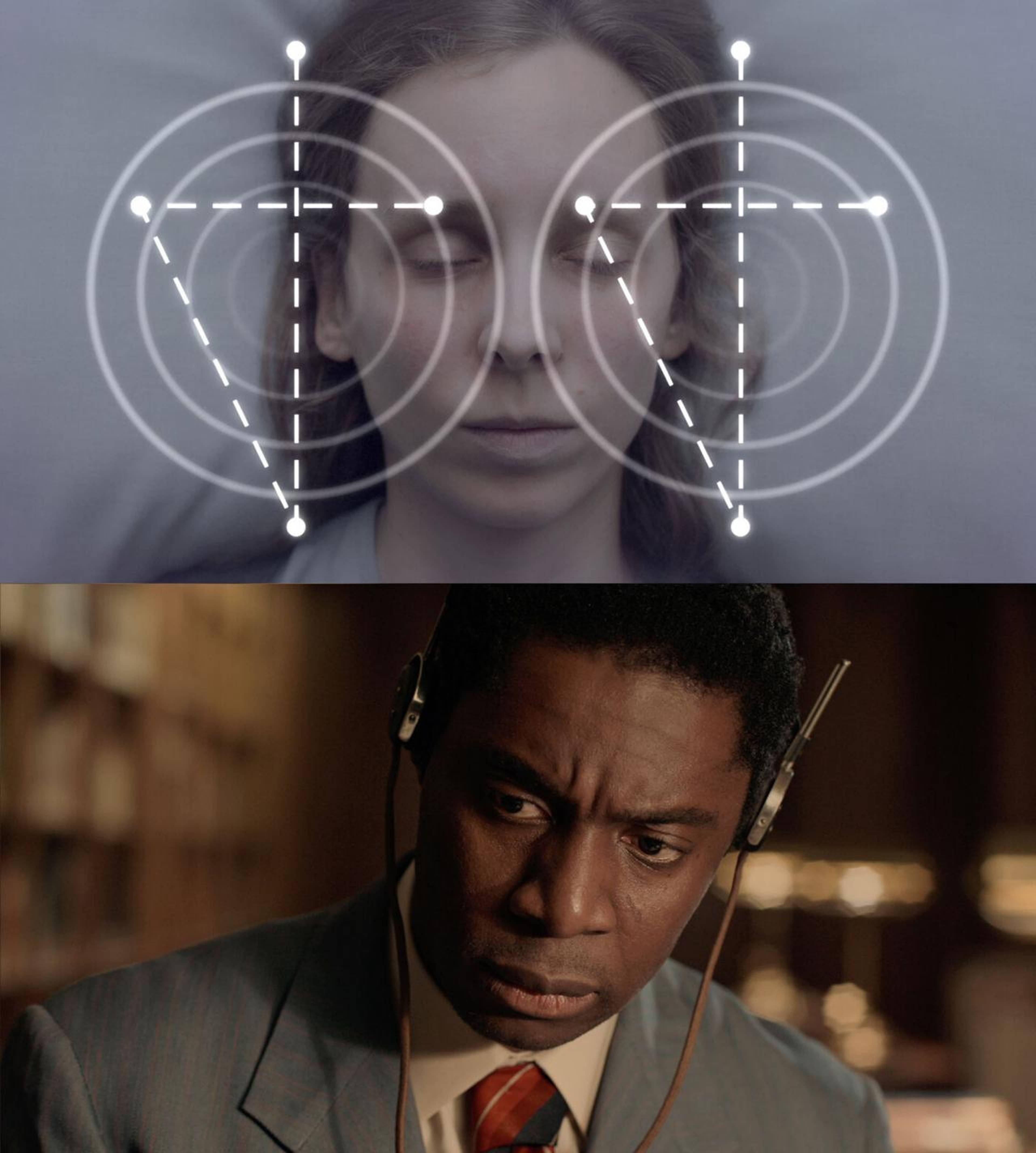

In another film, Gal’s Dark Continent (2023), we inadvertently eavesdrop on the psychotherapy sessions of Mademoiselle B., a white, racist French woman drawn from the writings of Franz Fanon, with an unsympathetic male therapist. Suffering from tics and spasms, and haunted by the sounds of African drums, she talks under hypnosis through her memories and visions. As the film concludes, it is revealed that the root cause of her affliction is her authoritarian father, who played African music on the radio every evening during her childhood, likewise problematizing the stark division between the oppressor and the oppressed.

Despite its irrationalist, pre-Freudian aura, curating a festival about demons and humans could easily shift the responsibilities of blame from aggressors to unknown evil spirits, as a Nazi soldier in Kavelina’s animation alleges to a Jewish woman that forces compelled him to burn her body. However, against the seductions of moral relativizations, Manichean rhetoric, or virtue-signaling, the exhibition invites us to map the parameters and contours of our own demonic gray zones.

Stills from Dani Gal, Dark Continent, 2023, video, 26 min. Courtesy: the artist

___

“Humans and Demons”

steirischer herbst ‘23, Graz

21 Sep – 15 Oct 2023