Georges Perec tried several times to think of a house in which to spare a useless room, “absolutely and intentionally useless.” Not a junk room, not an extra bedroom, nor a corridor, a cubbyhole, a corner. “It would be a functionless space. It would serve for nothing.” He didn’t succeed in planning nor doing anything. He didn’t know “how to expel rhythms, habits, how to expel necessity,” in the end.

Tolia Astakhishvili seems to have found a way to make rooms of this sort. It doesn’t mean they are empty. Usually, they are bristling with found objects, painting, photography, drawings, and collaborations with other artists. At Bonner Kunstverein, for a show she called “The First Finger,” she made enough rooms to form a house. The first one is big, dimly lit, and greets you with sundries, the kind of objects all of us try to make sense of in hallways: a ruler, a light bulb, an old analog camera, a solitary jack plug. But they are not stored in any caskets, on narrow benches. They are thrown on the floor along even less practical whatnots – a broken candle holder, a miniature television set, a miniature streetlamp. And they are covered with what seems like snow spray. A sort of secular, evacuated Christmas crèche.

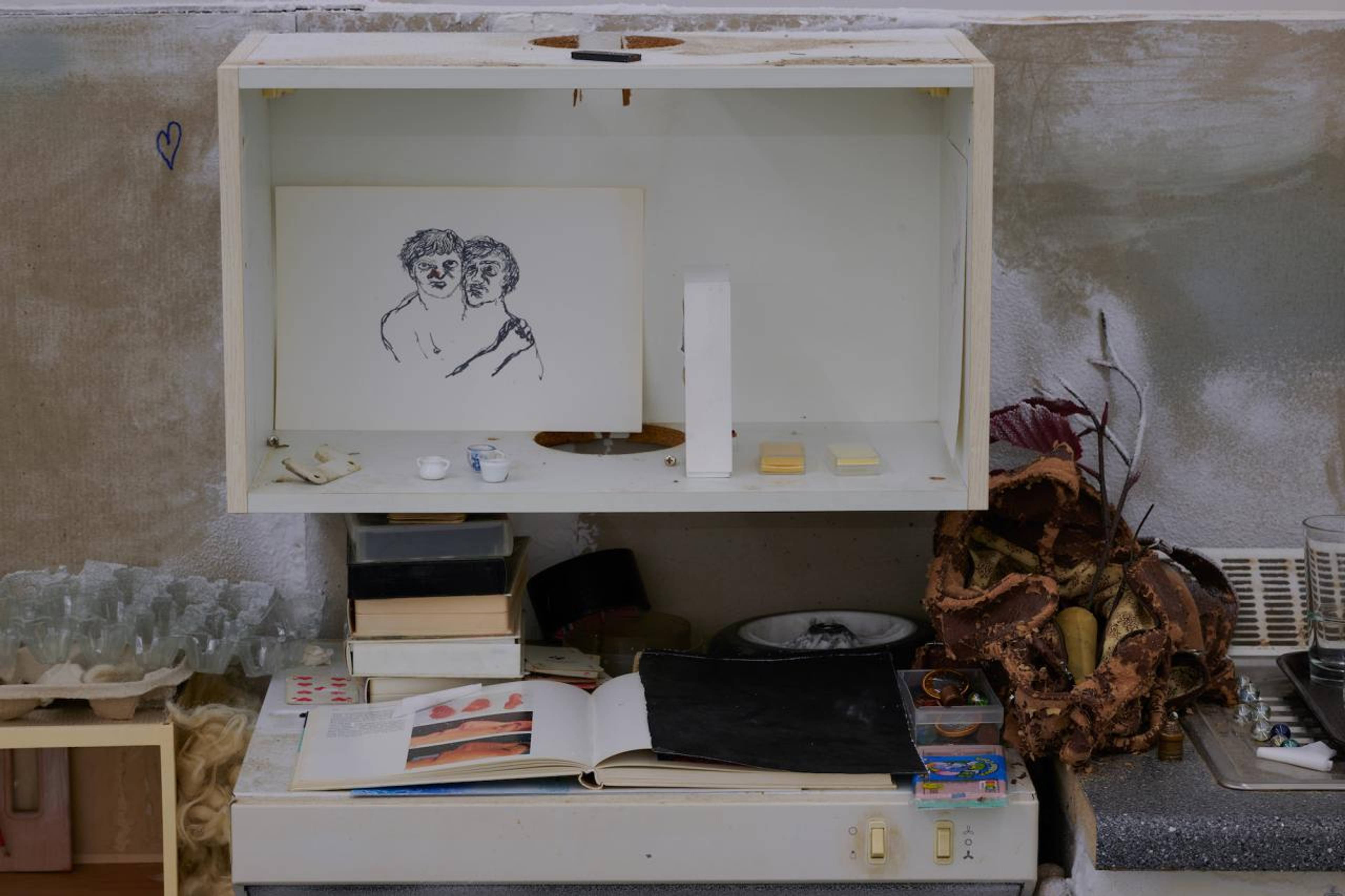

Behind it, a kitchen seems to have been abandoned as well, long ago, long enough to let mold grow, and heaps of dust, or rather something uncannier. There is an oven, a sink, and Amica, the dishwasher, but the rest of the cabinets are taken over by doll houses, and so many beings. A stack of glasses took up residence on a pocket boudoir. Ball-pen drawings leaned against the puppet walls sketch a bicephalous man forced to hug himself, another in a suit rests a spoon on his forehead and says “SPOON SEX,” with a grin. Some VHS movies lay on the extractor fan, next to a rhinoplasty book, next to a pack of cute Knabber Cash (edible paper bills for kids), next to a leather bag so worn-out it seems coming from the seafloor. On the ground, a baking tray blooms some sort of catnip. The oven bakes a starched cloth while radiating a ventilation sound, yet something seems to be trapped in there. A fly is beating its wings, or grains of sand are rustling, nervously either way.

Tolia Astakhishvili, Our garden is in Bonn, 2023. Installation view, Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn, 2023.

Tolia Astakhishvili, Our garden is in Bonn (detail), 2023. Installation view, Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn, 2023

What kind of tumors dwell in these appliances, what kind of rebirths? What kind of infestation, what kind of erotics? Perec would be contented to see rhythms and habits discharged here. But also new ones are seeping through the blight. Does this mean this kitchen has lost its use, its necessity?

The title Astakhishvili gave to her show, “The First Finger,” alludes to the mechanics of necessity, actually to the necessary cost of protection. To conserve major organs under extreme conditions, like frost, the body sacrifices it extremities. But how does it pick the first finger to loose? When do things get nonnegotiable, and which others are we ready to let go? Which one protects us by way of receding? Is the mold necessary to grow some new life, quirky lovers, a second head you didn’t know you possessed, or to erode what we actually don’t need there below? The use of a thing may lie precisely in its functional lack, in its disappearing, or re-appearing in diverted purpose. This is the uselessness Perec was craving, perhaps, the nothing needed among the functioning rest.

Tolia Astakhishvili, Entire, 2023, plasterboard, padding material, ventilation grille, pipes, construction sign, gym mats, punching bag, artificial snow, lamps, sound, 6 m ceiling lowered to 3 m x 15 m x 23 m

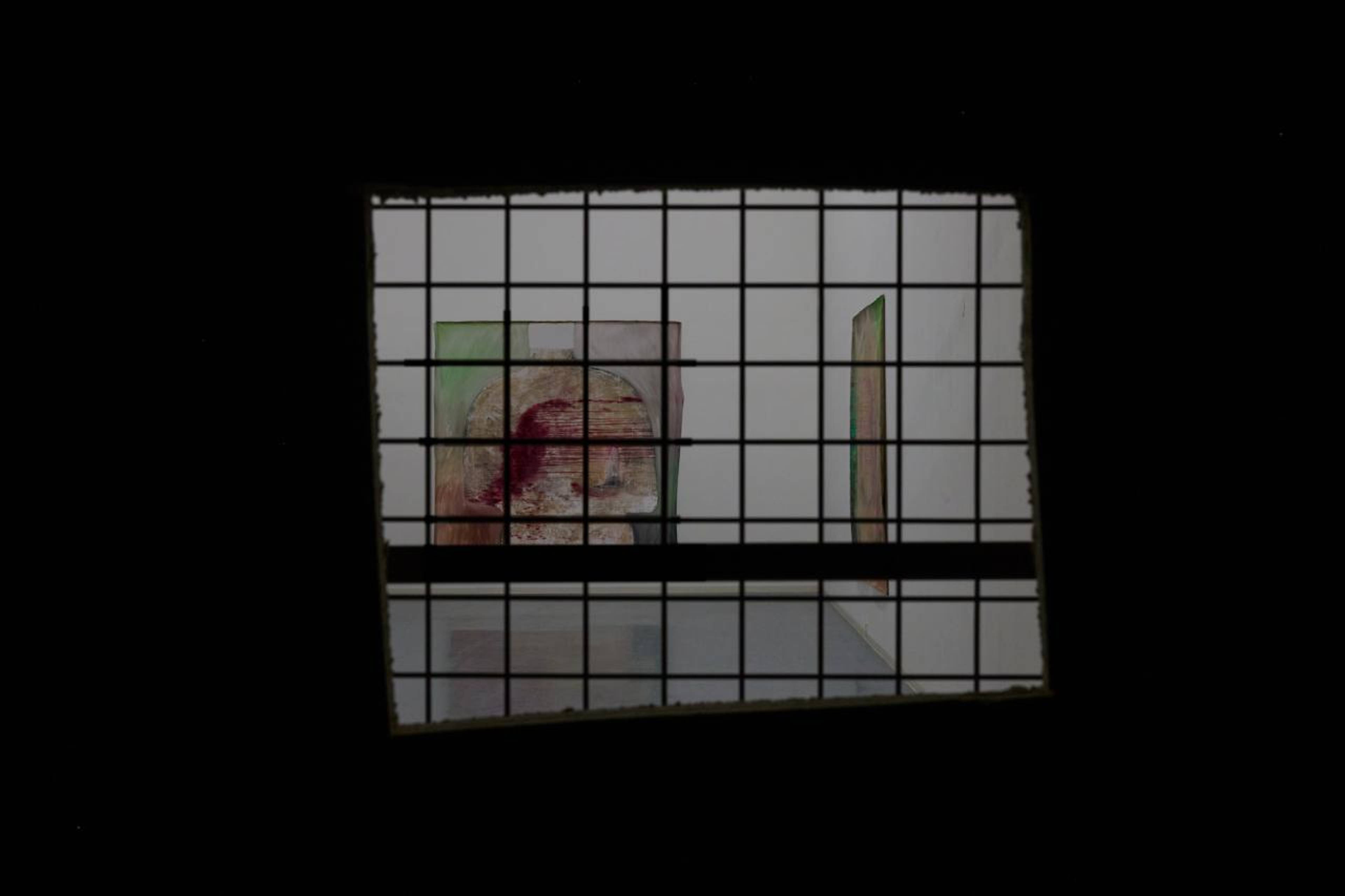

Past the infested kitchen, Astakhishvili’s home continues. A dark corridor leads to a vast room, an army of pillars, faint beams of light leaking from cracks in the ceiling. If not a parking lot, it may feel like a brutalist cloister. This room is expelled to the point of almost nothingness, if it weren’t for some punching bags scattered on the ground in its darkest corner, and that same oven sound, this time coming from a grid in a pillar. Whose wings are caught in here? Are the ducts the same running through the second grid we see just behind the first? There, we don’t glimpse only sound, but a stretched-out corridor, dimly lit, a pale brown sofa in the foreground, and two large paintings by Ser Serpas in the back ( Untitled , 2022). They depict half finished, wounded torsos, a burgundy scratch bleeding from their skin. This space is called “Lust Room,” and we cannot get in there, sit in there. Protected because out of reach – it would be the description Lacanians give of libido.

Ser Serpas, Untitled, 2022, oil on canvas, 252 × 227 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin; Karma International, Zurich; LC Queisser, Tbilisi; Maxwell Graham/Essex Street, New York.

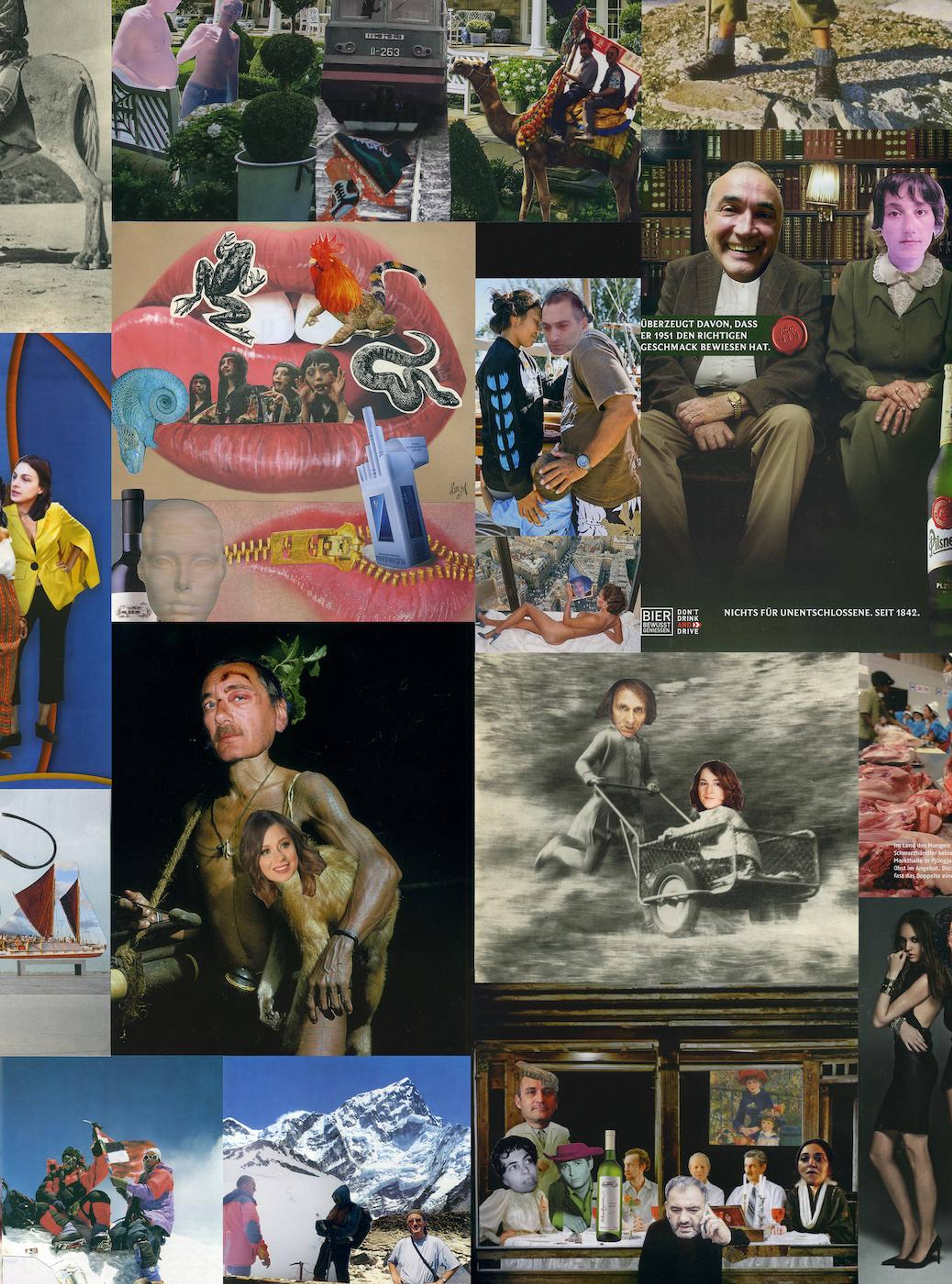

A few steps away another light is calling us, the only bright one in the show: I can’t imagine how can I die if I am so alive (1986–ongoing) is an explosion of images. This time, the collaboration is with the artist’s father, Zurab Astakhishvili, a children’s lung specialist and alpinist doctor who, since retiring a few years ago, began dedicating more time to something he managed to do only sporadically in the past: collages. The faces of friends and relatives, of both father and daughter, crowd over newspaper clippings. A teenage Tolia with the body of a groundhog is nibbling a cookie. Writer Kirsty Bell (who contributed to this exhibition with a text) attends an aperitif in an Egyptian crypt. The artist’s gallerist, Lisa Offermann, sways like a Broadway star as jewels fly around her; her partner, Nika Lelashvili, smiles with a bulky Hawaiian necklace in spite of a shark looming menacingly from the ceiling. The juxtapositions are hilarious, beyond being formally sophisticated, their spirit so refreshingly light-hearted (at the very least, eclipsing the current wave of hypersentimental portraiture ). Occupying the floor of this room are tiny cardboard models of homes, of furnitures: all the flats Zurab Astakhishvili lived in, beginning with his childhood one, one room for the whole family.

olia Astakhishvili and Zurab Astakhishvili, I can't imagine how can I die if I am so alive (detail), 1986–ongoing, collages

Psychologists say that if children are troubled, they draw motionless houses, rigid, not alive. Tolia Astakhishvili’s one is bursting with animation, of sick and vital spirits, abandoned and libidinal, somber and funny under one roof. A happy death, Albert Camus used to call the one you end up accepting, the finger lost, the use, the habit, the necessity expelled. A desolate nothingness may be the antechamber that protects your lust, then, or that invites your most comic associations. “He who has learned how to ‘let be’ restores all things to their primal freedom; he leaves all things to themselves.” Gelassen , wrote theologian Meister Eckhart in the German Middle Ages, are those who no longer look at objects and events according to their usefulness, “but who accept them in their autonomy.” A useless room doesn’t mean empty, then, it means self-governing, free.

Tolia Astakhishvili, Our garden is in Bonn, 2023. Installation view, Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn, 2023.

Tolia Astakhishvili, Our garden is in Bonn, 2023. Installation view, Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn, 2023

___

“Tolia Astakhishvili: The First Finger”

Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn

25 Mar – 30 Jul 2023

“The First Finger (chapter II)”

Haus am Waldsee, Berlin

23 Jun – 24 Sep 2023