Remember “Il Tempo del Postino?” Or “14 Rooms?” Both exhibitions, albeit originally conceived in other contexts, were on view in Basel during Art Basel in 2009 and 2014, respectively – and both made quite a splash with their far-reaching turns towards temporality. “Il Tempo del Postino,” co-curated by Hans-Ulrich Obrist and Philippe Parreno, took to the theater stage and gave visual artists a timeframe instead of a designated space, whereas “14 Rooms,” co-curated by Obrist and Klaus Biesenbach, took place within the fair itself and showed fourteen separate, simultaneous performative pieces.

Fast-forwarding ten years, a show at Fondation Beyeler seems, with its emphasis on temporality, to pick up right where “14 Rooms” left off. This next Obrist-Parreno collaboration, conceptualized together with Fondation Beyeler director Sam Keller, Mouna Mekouar, Isabela Mora, Precious Okoyomon, and Tino Sehgal and “in close collaboration with the participants,” as the booklet informs, is meant to work like a “living organism.” “Living,” here, means a meandering, moving, ever-changing thing, unexpected, somewhat porous and permeable, fluid, unfixed, and, not to forget, somewhat arbitrary (even if the network of artists and curators that “comes to life” here is anything but).

Philippe Parreno, Membrane, 2023 and Fujiko Nakaya, Untitled, 2024. Installation view, Fondation Beyeler, 2024. Courtesy: the artists. Photo: Mark Niedermann

To start with, the title is constantly changing. At the time of writing, it is “The Lateness of the Hour,” preceded by the equally grand “Dance with Daemons,” “Echoes Unbound,” and “Cloud Chronicles.” Even if the show affords its participants room to play, most of the works variously emphasize change, porosity, or simply movement – and many function in an almost cinematic style. Some, like Parreno’s (*1964) own Membrane 2 (2024), a techno-futuristic and towering totem in the garden, tend to react to the curatorial stipulation with elaborate technological effort; others, like Fujiko Nakaya’s (*1933) sculptures of fog, which she has used since the 60s to dematerialize and somehow soften sculpture, are rather minimal, the enchanted vagueness turning the museum into a kind of haunted house.

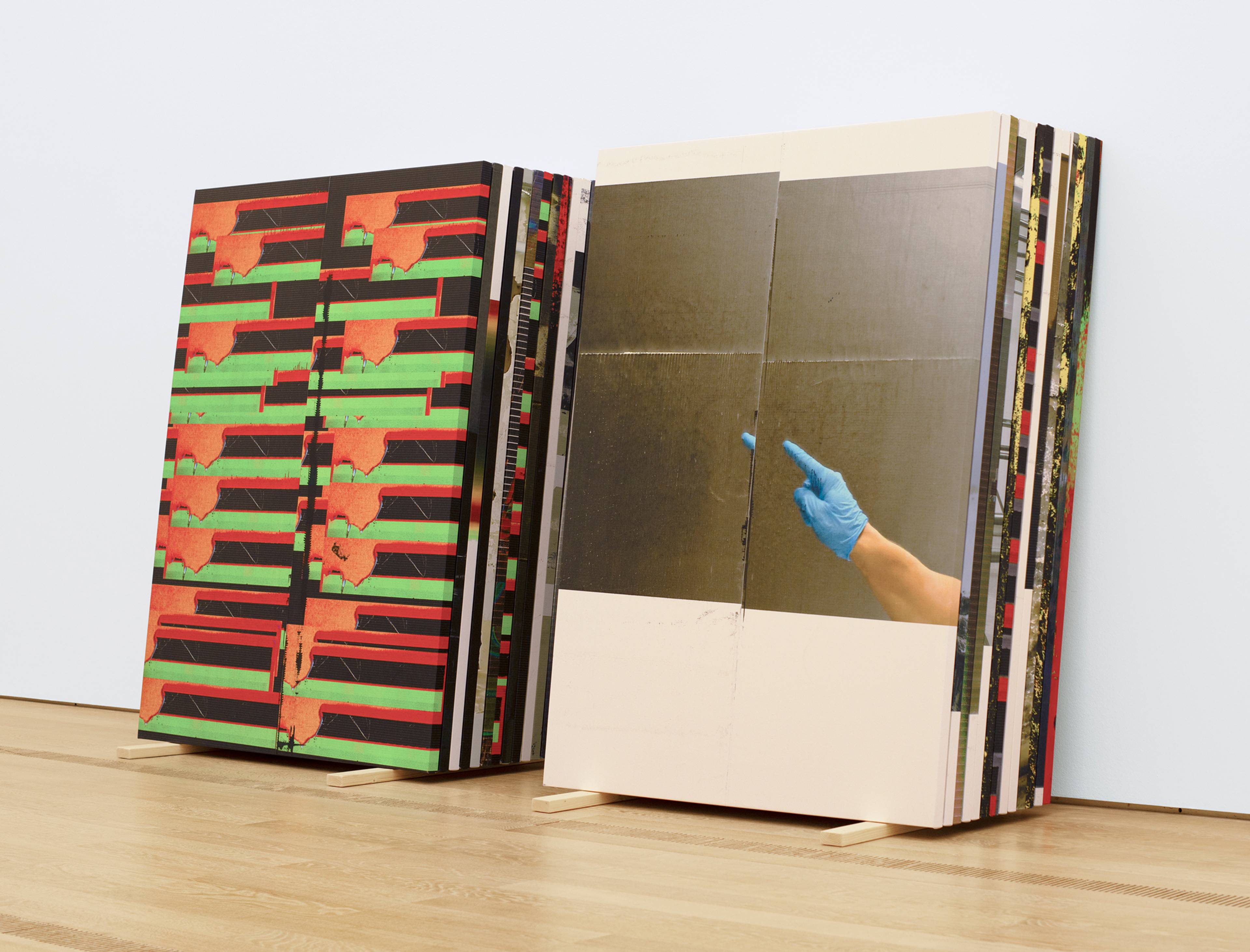

Inside, the fairy-tale atmosphere continues. What was just there, like Rachel Rose’s (*1986) publication What Time Is Heaven (2024) with photographs of the Fondation’s empty rooms, or Pierre Huyghe’s (*1962) helmet-like sculptures, is suddenly gone – small, movable contributions that have no fixed placing, but are constantly relocated. The feeling of a stage-set or movie studio prevails, charging quite some of the sculptural contributions with the aura of props: In Adrián Villar Rojas’s (*1980) dystopic The End of Imagination VI and The End of Imagination VII (both 2024), alien-like structures emerge from household devices (e.g. a washing machine) straight out of early Cronenberg.

View of “What Time Is Heaven,” Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 2024. Photo: Mark Niedermann, Stefan Bohrer

View of “What Time Is Heaven,” Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 2024

If you want to single out specific works from the overall “organism,” those by Arthur Jafa (*1960) and Cyprien Gaillard (*1980) – actual movies presented in black boxes – are among the most convincing. Accompanied by a sparse jazz soundtrack, Jafa’s ultra-minimal, grainily abstract, black-and-white composition LOML (2022) eulogizes the artist’s long-time friend and intellectual companion, the late cultural critic Greg Tate. With the simplest means, this work hints to liveliness in a wholly other, almost dialectical way – not so much bringing to life an inanimate techno-nature with considerable effort, but silently pointing towards the passing of time and life’s invariable end in death.

Gaillard, meanwhile, plays up the 3D technology used for Retinal Rivalry (2024), to the point that its powerful visceral images usurp narrative as the actual content of the work. The film tours through Germany, the French artist’s homebase for some years now, with the expat’s estranged “parallax view,” touching on Johann Sebastian Bach, romanticism, Oktoberfest, Werner Herzog. Overall, Gaillard seems to reimagine the proverbial German tendency for inwardness as an interior space like a recycling container full of stinky beer bottles – German identity, an endless recycling process.

Cyprien Gaillard, Retinal Rivalry, 2024. Installation view, Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 2024

Adrián Villar Rojas, The End of Imagination VII, 2024. Installation view, Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 2024

However, the exhibition’s real centerpiece, the organism’s “heart,” is Sehgal’s (*1976) contribution. Much like in a “making of” feature (another movie-world format!), Seghal stages the hanging itself as a work, art handlers schlepping paintings in and out constantly over the course of the exhibition. Furthermore, Sehgal follows some sort of real-time, collage-like approach that cuts right through the conventional rules of presentation and art-historical categories: forming a long meta-horizon from side-by-side landscapes by Van Gogh and Ferdinand Hodler; having a thin Giacometti sculpture contemplate a Francis Bacon triptych, its left plate missing, its right one replaced by a Rudolf Stingel canvas; or facing a series of busts towards one another in intense conversation. Not only is the hanging in permanent flux, but the works, too, feel animated, freed from the deadening weight of art history.

Here, though, where the show’s appeal becomes most convincingly apparent, so too do its pitfalls. As simple and effective a gesture as this is, it is only awe-inspiring and “vitalizing” with so-called “masterpieces” – pieces seemingly taken out of history, untouchable, and validated for eternity. It is a form of playfulness that requires a certain height to fall from. Seen that way, the freedom the show takes for itself and grants to the artists and works alike, feels not only utterly necessary, refreshing, and beautiful to witness; it also appears as a luxury one must be able to afford in the first place.

Duane Hanson, Painter, 1977. Installation view, Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 2024

Dozie Kanu, Cloak-room, 2024. Installation view, Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 2024

Huyghe/Collection. Installation view, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2024. © Josef Albers and Anni Albers Foundation, 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. Photo: Mark Niedermann

___

“What Time Is Heaven”

Fondation Beyeler, Basel

19 May – 11 Aug 2024