The essence of dance is bodily movement. Its choreography relies on the spatial arrangement of highly disciplined, self-aware, and precisely – as well as joyfully – moving people. Ballet, an aesthetic product of court culture and, later, of the institution of opera, is, at its core, the high art of social choreography, fleshing out how hierarchies of power and their ideologies direct our motion. For the duration of ImPulsTanz, the master of contemporary ballet, William Forsythe (*1949), who has danced and choreographed ballet since the 1970s, has installed four room-spanning installations in a solo show at MAK, Vienna, each one focused on an essential component of dance: critical self-observation; spatial and relational play; the arrangement and coordination of body parts; and the medial surveillance of the moving body through video documentation.

At the show’s entrance, an introductory wall text succinctly sets out how viewers are meant to interact with the installations with which Forsythe has choreographed museum space. The first, Attempt to walk without rhythm (2023), invites museum visitors to move against the instinct to walk with regular speed and rhythm. In contrast to choreography, which scores every bodily movement on the basis of mostly extant dance vocabularies, museum visitors can move here as they please, even as they attentively walk the exhibition’s beginning.

City of Abstracts, 2000. Installation view, MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, 2024

This feeling of freedom begins to change with Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time, Nr. 2 (2013), an asymmetrical arrangement of 400 pendulums hung from the ceiling. At the opening night of show, I watched a group of young, artsy-looking people jumping over and around the suspensions. Consciously or not, they precisely followed what Forsythe had in mind with this installation: avoiding contact with the pendula to create their own micro-choreographies within inside the museum’s tightly regulated social space. Others, in contrast, circumambulated the objects more casually, unexcitedly, without great physical effort or visible thought.

This installation spotlights the living human body as object of both action and observation. The material condition of a swinging pendulum, a frequent point of comparison to the dancing body, is representative of several laws of motion, such as gravity and the equilibrium position – namely, how the Earth rotates and time can be measured. It is the interplay of empiricist observation of natural “objects” and the social constructivism of physics that draws attention to the pendulum moving uni-linearly, at one speed, following an intrinsic impulse, in opposition to the interaction Forsythe envisioned.

Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time, Nr. 2, 2013. Installation views, MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, 2024

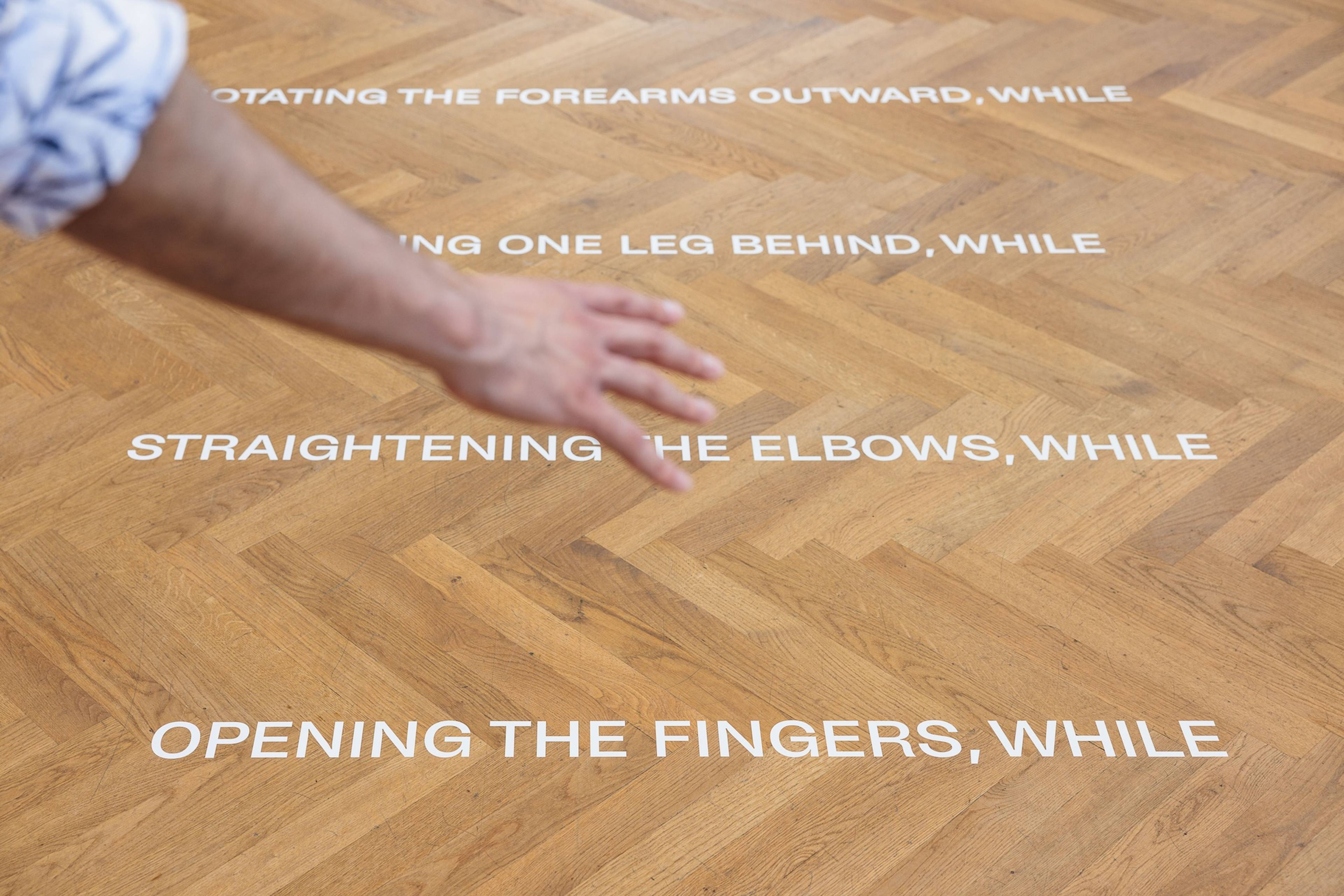

A third installation, Putting one foot in front of the other (2019), pushes the intention of the exhibition to its peak. Glued to the floor in a white, twenty-meter line, highly specific instructions guide visitors from one end of the room to the other: … MOVING THE EYES OPPOSITE THE HEAD, WHILE BENDING AND STRAIGHTENING THE KNEES, WHILE … Head bent down to read the tasks, I found it challenging to engage with the choreographic scores – so I stepped out of the line’s textual approach and walked alongside, at my own rhythm, moving my body as I wanted to – and was not the only one to do so.

Finally, in an LED video installation, City of Abstracts (2000), a camera records visitors standing in front of, moving within, or leaning away from a projection of its video feed. Highly compressed and time-lagged, the staggering, distorted representations reminded me of the poor quality of how some dance studios’ concave mirrors show their movers. Unlike analogue mirrors, the technology here is unable to record every bodily movement – when I jumped in the air, the camera did not register it, leaving my projected doppelgängerin standing statically on the ground, next to the other people present in real time and space. More than two decades after its debut, and perhaps caught up to by the institutionalization of participatory and immersive performance (e.g., dance in the museum) and its immediate documentation on social media, the inclusion of City of Abstracts casts a light on the rapid deployment of automated image technologies and its own obsolescence. And yet, the 21st century’s hybrid culture has not changed the anatomical condition of the human body – it only impacts how we conceive of and apply ourselves in everyday life.

Attempt to walk without rhythm, 2023. Installation view, MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, 2024

William Forsythe’s visual-art installations – in which not a single muscle of the body is told how to fire – open up an important public forum to debate: Who are the objects, and what are the objectives, of bodily inscribed choreography in dance today? While many contemporary practices and performance forms of ballet are attempting to further break free from approaches to making dancers treat themselves like task-based choreographed objects (e.g., Florentina Holzinger’s sadomasochistic approach to performing the techniques of ballet), Forsythe’s very own form of ballet represents it, above all, as a spectacular and virtuosic form of stage dance. As an aestheticized ideology, meanwhile, his conceptually objectless installations reveal dance itself as nothing less than a highly stylized social choreography that relies, like that of its professional practitioners, on mannerly, conditioned disposition. Museum visitors, no less than ballet dancers, like to have their movements joyfully directed by an invisible mind.

___

“Choreographic Objects”

MAK, Vienna

11 Jul – 18 Aug 2024

Shifting Symmetries

Wiener Staatsoper, Vienna

11, 14, 16, 18 & 23 January, 2025