That part of the party colored by genre – that penchant, human or chemical, to bend toward plot, character, sense-making. At daybreak, over breakbeat, on a smoke break – tired or wired or rolling profoundly – the onset of tomorrow’s narrative announces itself in the radical imminence of the rave. Writer and media theorist McKenzie Wark calls this sublime, techno-induced state a “sideways time,” and a creative stimulus. In time unfixed, does narrative visit?

Last June, I attended a wet-dream-themed Brooklyn warehouse party that seemed hesitant of its growing “circuit” adjacency, of the obvious expectation to have pride during Pride, and to express it with impressive columns of rainbow light and forty-dollar presale tickets. Having danced the floor from empty to capacity, a friend and I collapsed by a couch in the adjoining space – probably a storage container, tonight both smoking lounge and somewhat reticent darkroom. Beside us was a beefy guy with that ubiquitous and unchanging “subversive basic” look: MISBHV top; cyber-sigilist, Gentle Monster sunglasses; the neon of a Nasty Pig waistband half-visible under cargos. Hours earlier, he had been loose and aggressive and annoyingly inconsistent in his dancing, never comfortably enmeshed in the shared body of the crowd; docile now, we watched him lounging indiscriminately beside us, on the sofa’s cum stains and Club Mate puddles. Lost in our “sideways time,” it was a while before it struck anyone in the room that he was unconscious and unresponsive, G-ed out.

The paradox of the rave is this: The lived experience you roll with is not the narrative you come down with. In memory, this party arrives with the clarity and wistfulness of folktale. Like Snow White in her glass coffin, the dancer awaited the paramedics somebody called; all along, the darkroom’s creatures copulated slowly, pausing only to disappear key-tips into their noses. The paradox of writing the rave, meanwhile, is that even if the party feels plotted, dramatized, poetical, a creative retelling of last night’s party can quickly go the way of conveying last night’s dream: uninteresting to most listeners, unless they themselves feature, or if there’s sex, or depravity, or a celebrity appearance. If my recollection be allegory tonight, it’s only through the generosity of retrospect, of knowing the dancer was revived and sent home.

The truth that has resonated outwards seems all the more profound – how to discern, if one even should, the individual from their place in the collective.

Yet, a canon of rave-writing not only persists, but grows. Rainald Goetz’s 2021 autofiction Rave might have come first, published the same year as Jeremy Atherton Lin’s historical study Gay Bar: Why We Went Out. Wark’s 2023 Raving followed, impactful for its intellectual approach; then, it was the art-book market, marked by David Kennerley’s GETTING IN and A24’s On The Dancefloor – collections, respectively, of 90s gay-club flyers and cinema’s most iconic dance scenes. Despite the folksy regionality of nightlife, the specificity of its time and place, there’s a relentless demand for discotheque epistles across genres and forms. Lorde wastes MDMA on a backyard rendezvous in “What Was That” (2025); Charli xcx and her acolytes have another little line; Nicole Kidman, in Babygirl (2024), stumbles through New York’s techno-mecca Basement in mustard-yellow business-formal.

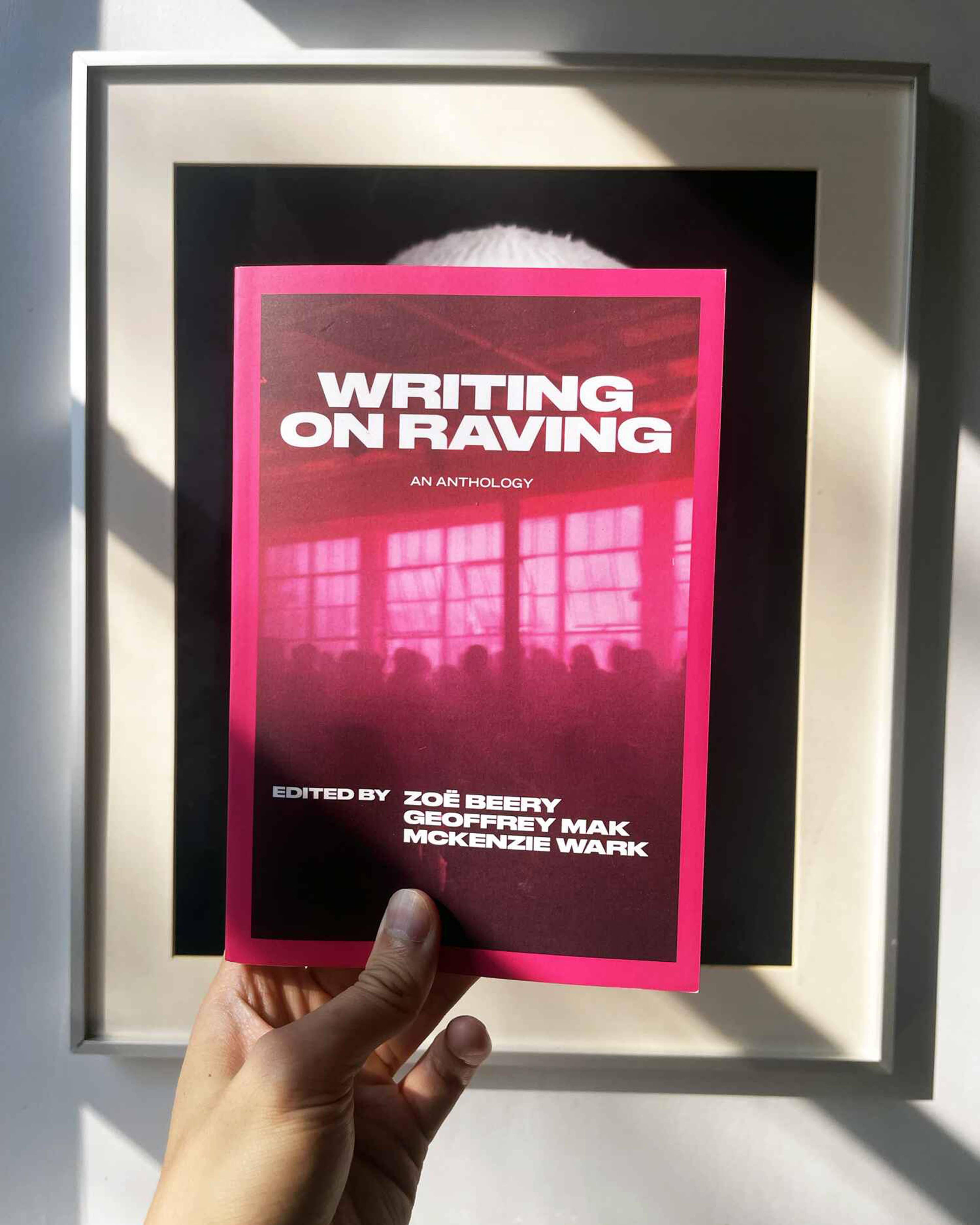

You could argue that the growing cultural obsession with the rave dispatch – the post-COVID marriage of nightlife aspirationalism and mass introspection – is the crucible in which Writing on Raving: An Anthology, from OR Books this May, was alchemized. Except that the editors – Wark, critic and Spike editor-at-large Geoffrey Mak, journalist and organizer Zoë Beery – invented the very culture that demands this writing. Since 2021, Writing on Raving has staged readings in Brooklyn’s techno mainstays (Nowadays, Paragon), usually followed by afterparties: a time for theory and a time for praxis.

Writing on Raving: An Anthology, 2025. Courtesy: OR Books, London/ New York

Left to right: Editors McKenzie Wark, Zoë Beery & Geoffrey Mak. Photo: Guarionex Rodriguez, Jr.

Writing on Raving is a compendium of the series’s best contributions: some from writers who rave, others from ravers who write. And like a continuous mix, its stories operate together with techno logic, in a looping variation on themes: the counterpoint of labor and leisure; real subversion, even criminality, and the lack thereof; the tradition of secrecy and the necessity of an archive, which itself begets surveillance; ghost stories with varying degrees of metaphor and literalism. Some essays, such as Kumi James’s “A Politics for the End of the World” and MX Oops’s “Ecstatic Aesthetics: Mind Training on the Dancefloor,” cruise high theory. Others approach High Modernism, like an excerpt from Anne Lesley Selcer’s novel CLUB SPACE (2024), which, in a raver’s retelling of the soliloquy in James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), puns “Bloom: Molly!” Some pieces are just high – deliciously or ridiculously high, with the curatorial amateurishness of naïve art.

The role of anthology is crucial in all of this. In his poem “Among School Children” (c. 1926), WB Yeats famously wrote – and Andrew Holleran, for the title of his 1978 proto-rave novel, famously borrowed – “O body swayed to music, O brightening glance, / How can we know the dancer from the dance?” If he meant simply to approximate the inextricability of body and soul, the truth that has resonated outwards seems all the more profound – how to discern, if one even should, the individual from their place in the collective. This is the ethic of the rave, but also the goal of anthology: the guise of energetic (or political, or sexual) coherence across private lifeworlds, collected under the very arbitrary criteria of liking the same music, living in the same city, being under the same influences.

E.R. Pulgar

Afsana Mousavi, Nowadays, Queens, 2023

Zoey Greenwald, Poetic Research Bureau, 2025

Slant Rhyme, Paragon, Brooklyn, 2024

If there’s a refrain among the anthology’s contributors, it’s the perspectival diversity among today’s ravers. In “Ascetic Hedonism,” theologian Linn Tonstad reckons with the rave’s concurrent impulses toward monasticism and indulgence; that “we rave [...] with people whose politics we despise, whose haircuts we dislike, who fucking film us when we dance” is a social truth, though not necessarily a historical one. In the most pessimistic sense, the rave promises, but rarely delivers, a collective effervescence to its attendees. This pipe dream of ritualized, communal transcendence is hauntological – the lingering byproduct of yesteryear’s ecstasies made myth in their recounting. The ghosts of truly subversive or glamorous or underground parties – those of shuttered, legendary New York clubs Paradise Garage or Studio 54, innumerably invoked across Writing on Raving – have entrapped today’s ravers and nightlife trustafarians alike in a lucrative spiral of nostalgia, aspiration, and (spiritual) hangover. “This is glamor,” theorizes Zoey Greenwald in “Cigarette Girl”: “you take a past you didn’t know – that didn’t exist – and you go ahead and sell it to the future.”

But if there’s dissonance between “community” in ravespace and the different experiences lived therein, there is also room for harmony in individual specificity, in diversity of ideas and bodies and movements. The rave, like the anthology, is an exercise with a utopian claim that being together will itself create the reality of togetherness. In Beery, Mak, and Wark’s introduction, they stress that any “good book, like a good party, is one where everyone has something different to give.” Community, creative or recreational, requires that its members tolerate (or acknowledge) the friction between their distinct desires, their conflicting ideologies, between the past’s future and the present’s past. The easy sheen of unity – in written rave or rave, written – belies the good door, the good DJ, the good editors that begot it.

___

Writing on Raving: An Anthology is published in paperback and as an E-book by OR Books.