Diamond Stingily, “I’m Not Coming Back Here”

29 Apr – 1 Jul 2023

Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi

It took her a long time just to write down the word she always carried along: “home.” The fifteen-year-old heroine of Octavia’s Butler’s novel Parable of the Sower (1993) had to lose her place of belonging in order to embody the only lasting truth we humans can rely on: perpetual change.

The motifs Diamond Stingily (*1990) has silkscreened on mirrors show her family home in Chicago. She doesn’t live there now, but used to with her mother, grandmother, and siblings as a teenager. Some are Stingily’s personal snapshots – a simpering curtain shielding a kitchen, a fuzzy crucifix. Others are details of images used on the realtor’s website to sell the property after her mother and grandmother passed away – neat shots of the facade, the garage, the carpeted staircase. Which parts of you, which places, which ghosts, remain inscribed in your image? Which is most difficult to write down, in order to administer loss? Per Butler, people who have no homes will build fires.

View of Diamond Stingily, “I’m Not Coming Back Here.” Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin. Photo: Graysc.de / Dotgain.info

View of Diamond Stingily, “I’m Not Coming Back Here.” Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin. Photo: Graysc.de / Dotgain.info

Hiwa K, “Like a Good, Good, Good Boy”

28 Apr – 1 Jul 2023

KOW

In the realm of dogs, verticality is not really a dimension of space. As in the world of prisons, it is a measure of power – “Sitz!” – says Foucault in 1973. In Hiwa K’s (*1975) largest video work, installed on KOW’s upper floor, a camera drone hovers slowly, horizontally, over a thick rope stretched across rooftops and streets of Sulaymaniyah, the artist’s hometown in Iraqi Kurdistan. The rope literally ties together his family’s modest former house, now a ruin; his school; and the Amna Suraka prison, a theater of atrocities committed by the Saddam Hussein regime. In another video, the artist and his former classmates gather on the school rooftop to share, from “above,” the pain that they suffered under that regime within their homes, schools, and prisons, as well as the struggles to abide by the global labor market that came after the regime’s overthrow, at the expense of their Kurdish heritage.

The vertical rises up, commands, flattens. Kurdish culture, by contrast, is organized horizontal: relations are loosely ranked, narratives oral, melodic, and fluid, and institutions mainly absent. Kurdish people are not good, good, good boys and girls.

View of Hiwa K, “Like a Good, Good, Good Boy.” Courtesy: the artist, Prometeo Gallery Ida Pisani, and KOW Berlin. Photo: Ladislav Zajac

Rhea Dillon, “We looked for eyes creased with concern, but saw only veils”

26 Apr – 10 Jun 2023

Sweetwater

How much do credos bewitch? If you get the blondest hair, people will love you. Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye (1970) hijacks Dick and Jane , a mid-century book series with which US schoolboys and girls learned how to read, how houses are made, how red is the door, how mother, father, Dick, and Jane smile, how pretty they are, how all four are white and have blonde hair – unlike Morrison’s little protagonist, Pecola, who is black, has brown eyes, and feels ugly.

Rhea Dillon’s (*1996) show at Sweetwater translates narrative ingredients from the novel into sculptures. On the wall left of the entry, copies of a Dick and Jane book are inset in frames made from mahogany – a wood indigenous to West Africa used to build slave ships – and coated in black with never-drying, anti-climb paint, except for cutouts that expose a drawn, blue eye and the plea “See me, Mother, see me!”

Pecola loves chewing Mary Jane candies and drinking milk from a Shirley Temple-emblazoned glass, white girls smiling from their containers, blonde hair in gentle disarray. At Sweetwater, that specific blue glass is half filled with Mary Janes that Dillon herself has chewed and spat out, displaying the disgust underneath the desire for a sweet life. “There can’t be anyone,” writes Morrison, “I am sure, who doesn’t know what it feels like to be disliked.”

View of Rhea Dillon, “We looked for eyes creased with concern, but saw only veils.” Courtesy: the artist and Sweetwater, Berlin. Photo: Joanna Wilk

Rhea Dillon, She was washing dishes. Her small back hunched over the sink—a winged but grounded bird, intent on the blue void it could not reach, 2023, brass and polyester, 21 x 9 x 12.5 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Sweetwater, Berlin. Photo: Joanna Wilk

Liz Craft, Augustin Katz, Franziska Lantz, Zoe Metra, Josip Novosel, Ola Vasiljeva, “My eyes like shovels”

28 Apr – 15 Jul 2023

HUA International

While none of the artists featured in this group show ostensibly has anything to do with Naples, they seem to be – the curator, Gigiotto Del Vecchio, certainly does. Cunning and burlesque, dramatic and jocular, the works exude a theatricality that makes the title of the show programmatic: a vision that verges on brutishness. Liz Craft (*1970) has turned the left wall of HUA’s garret into a sort of catacomb, an array of dark blue ceramic tiles spooked by mushrooms candleholders, while a wood and papier-mâché marionette with six eyes sits on a chair and looks at the candles, almost annoyed by the playhouse behind her back. Center stage is Franziska Lantz’s (*1975) installation, all debris found on the banks of the Thames – animal bones, clay pipes, a motorcycle helmet, military jackets, the fragments concocted into dreamcatchers or skeleton puppets. All the while Augustin Katz’s (*1995) satyr, in Boneshaker (2022), sneers at them in a blood-red ecstasy.

The show manifests a zaniness that feels refreshing, the same, though, that Sianne Ngai says is governing affective labor these days, the one that muddles work and play – the term, she reminds us, derives from “Zanni,” the trickster character from 16th-century Commedia dell’Arte.

View of “My eyes like shovels.” Courtesy: the artists and Hua International, Berlin

Paloma Varga Weisz, “Wilde Leute”

Stanley Brouwn

28 Apr – 29 Jul 2023

Konrad Fischer Galerie

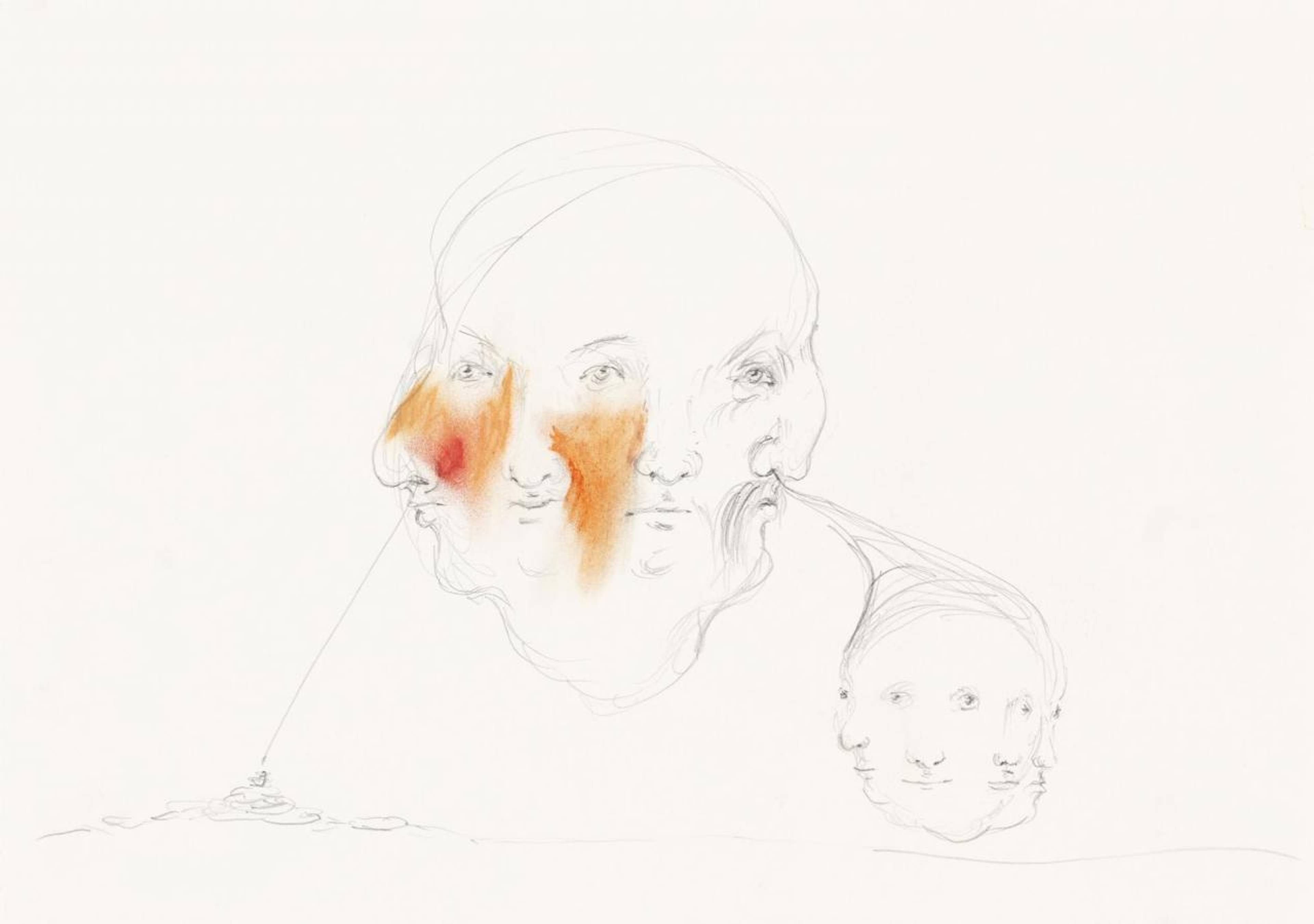

Paloma Varga Weisz’s (*1966) personae are watery, spectral, often half-animal. Among the numerous works on paper made between 1993 and 2023, running through all three upper floors of Konrad Fischer’s Berlin gallery, there is one figure with six heads, with either too-thick eyelashes, a haughty mien, or a gullible one, all flabby like undersea creatures. Guff (2023) is a deformed, rotten-green bust, almost faded away by an overly strong wind, its gaze distressed or clear-headed, the mouth rather slow-witted. The works on paper encircle a new group of large-format bronze sculptures of androgynous, somewhat gloomy creatures with animal ears, which, while recalling family portraits, are more aptly called Wilde Leute (Wild People).

The contrast with Suriname-born Dutch conceptual artist Stanley Brouwn (1935–2017), shown on the gallery’s ground floor, is striking. Visionariness and fantasy give way to dematerialization, impersonality, and an obsessive attempt to measure things, punctiliously, almost like a hysterical bureaucrat. “At this moment, the distance between stanley brouwn and marie adams comes to x feet, the distance between stanley brouwn and john adams comes to y feet, and the distance between marie adams and john adams comes to z feet,” reads a large label under a thin metal ruler called “1 foot.”

Paloma Varga Weisz, SPOOKY, 2020, pencil and oil pastel on paper, 29.5 x 42 cm. Courtesy: Konrad Fischer Galerie and the artist. Photo: Stefan Hostettler

___