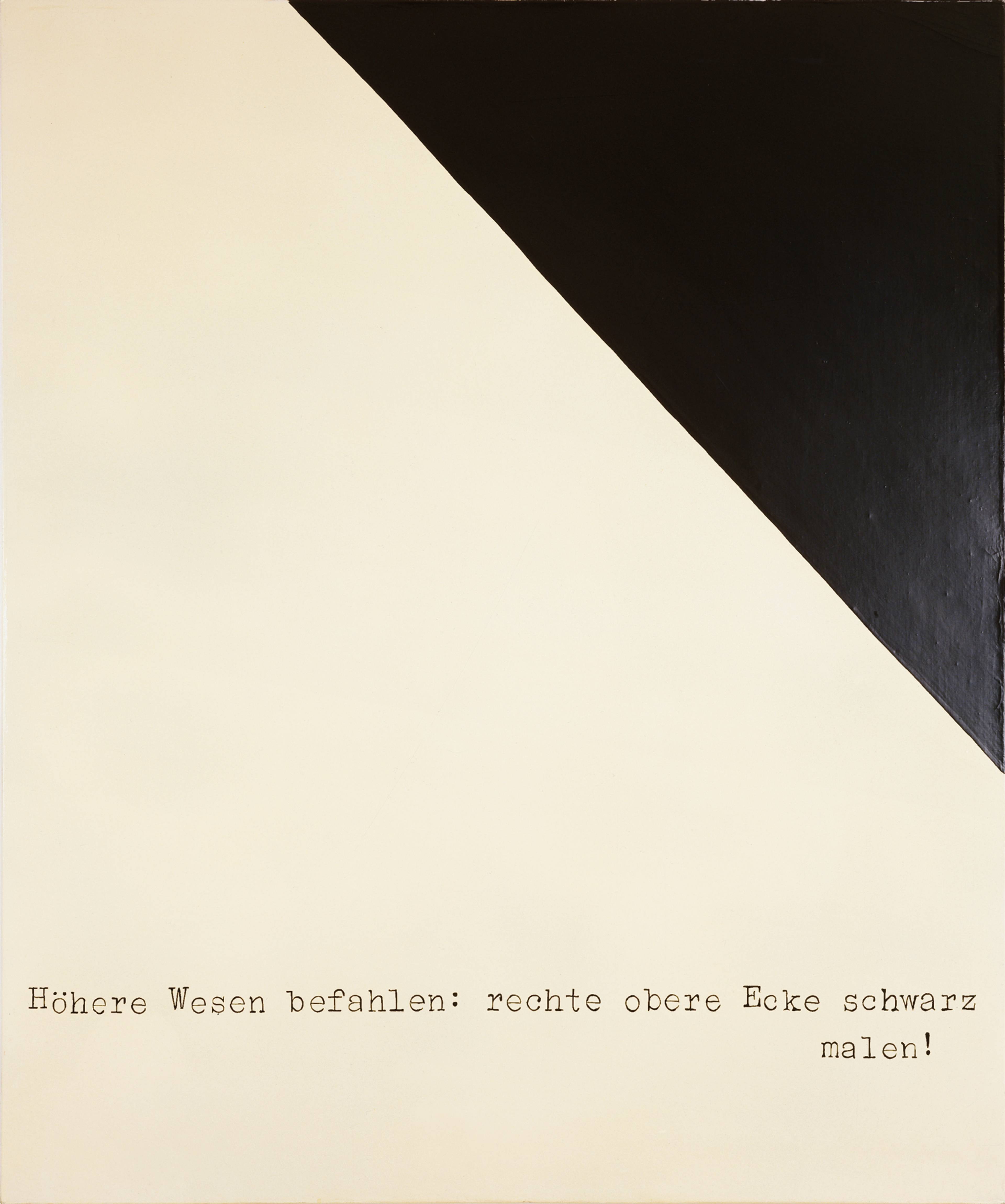

Higher Beings Commanded: Paint the Upper-Right Corner Black! It’s 1969 when the painter Sigmar Polke (1941–2010) hears these voices from offstage. He immediately obeys their command. A painting on the surface of which almost nothing is to be seen, which holds no secrets. A painting wherein there is nothing to discover but the black corner in the upper right, pushing into the edges of the 1.5 x 1.25 meter white canvas.

The laconic austerity, the simple, modest black and white, the scrawny letters of the typewriter. An image which distances itself so much from even being an image. It is hard to conceive of another work that goes so far in that respect. With Higher Beings Commanded, Polke became the chief ironist of contemporary art, founding a distinctly German variant of Pop Art and thumbing his nose at Warhol & Co.

It can also be understood as a painting about geometric abstraction, countering Kandinsky, Malevich, and their fellows with irony and pushing them to the point of absurdity. The explicit command contained within Polke’s painting makes plain that it is the higher beings who are responsible for the images humans produce, not the individual painter-genius. It is hard to imagine a more thorough satirization of the cult of genius, art history, or the notion of waiting for divine inspiration.

What are these “higher beings” actually reminiscent of? Of ghosts and extraterrestrial civilizations?

To assign Polke to a style is a hopeless undertaking; he was too fond of experimenting. Even as a student, he co-founded a new style, “Capitalist Realism,” which caricatured the longings of postwar Germany, one ideally suited to exposing the petty-bourgeois values of the young West German republic. While the art world still preferred the grand abstract gesture, Polke painted everyday things: cookies, Kaba cocoa cans, sausages, sausages, and yet more sausages – German Pop Art! Ever critical of ideology, his work was sometimes figurative and sometimes abstract; sometimes minimal and sometimes maximalist; sometimes based on, and sometimes breaking from, the classics. Thanks to his boundless explorations, he eluded simple explanations and the attempts of art critics to classify him.

For me, save for Albrecht Dürer, Polke is the most important German artist. He even painted the Dürer hare once, in 1968 – in his own way, of course. I met Sigmar at an age when mankind in general enjoys its intellectual peak – when I was eight years old! My mother and Sigmar were a “couple” for a while in the 70s, in the manner that people were together then, during that swell of emancipation and sexual liberation. At that time, he lived on a farm and kept a studio near Düsseldorf, in a town called Willich (not to be confused with the question Will ich? [Do I want?]).

Sigmar Polke working in his studio on Front of the Housing Block (Häuserfront), 1967

Sigmar Polke in the Eifel Mountains of West Germany, 1993. Courtesy: MoMA, New York. Photo: AVN

As a child, then, I was always dragged on the weekends to this farm, where I witnessed a debauched hustle and bustle that impressed me greatly. Those experimental weekends can be readily imagined with Timothy Leary’s slogan in mind: “Turn on, tune in, drop out!” While the adults were ingesting these strange substances, getting kind of weird, I had great fun painting the walls with Polke’s lacquer paints. Which, of course, drew a lot of applause and anticipated my later career. Although I had grown up in the then very hip and anti-authoritarian Kinderläden (nursery schools) and was hard to impress with rule-breaking and non-normative behavior, the way Polke went about things left a big impression on me. One way or another, it became clear to me that I also wanted to live like that, and not like the supposed bourgeoisie.

So, early on, I answered the question of what I wanted to be when I grew up with: the boss! Which later turned into an artist, because I also liked sleeping in very much. So, after my school days, the higher beings ordered me: Do art! And my (involuntary?) art career began.

What are these “higher beings” actually reminiscent of? Of ghosts and extraterrestrial civilizations? Are they the subjects of Freud’s theories, the “ego ideal” or the “superego?” Or are they a product of those regions of the brain, remote from consciousness, which contain age-old decrees? Or does our brain simply follow what has long been decreed in the regions of the brain remote from consciousness? Perhaps just the deterministic laws of nature?

View of “Sigmar Polke. Der heimische Waldboden. Höhere Wesen befahlen: Polke zeigen!,” Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin, 2024. © VG Bild- Kunst, Bonn 2024. Photo: Frank Sperling

Left: Sigmar Polke, Wo ist der Hirsch? [Where is the Deer?], 1983/84; right: Sigmar Polke, Die Schmiede [The Smithy], 1975. Installation view, Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin, 2024. © VG Bild- Kunst, Bonn 2024. Photo: Frank Sperling

Upper left: Sigmar Polke, Untitled (Dr Pabscht het z’Schpiez s‘Schpäckschteck z‘schpät bschteut), 1975; right, above and below: Willich: Sigmar Polke mit Schlangenhaut [Sigmar Polke with Snake Skin]. Installation view, Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin, 2024. © VG Bild- Kunst, Bonn 2024. Photo: Frank Sperling

The prominent neurophysiologist Wolf Singer completely denies the free will of humans. His research results show that conscious life is only a side effect of material processes in the brain. A decision would thus only be free if it fell on the platform of consciousness. To be free, moreover, this conscious deliberation process should be as distant as possible from external and internal constraints, such as an overpowering drive structure or a mind clouded by drugs – only then could this decision really be called free.

Both my own artmaking and founding of Schinkel Pavillon likely do not meet the threshold of Singer’s conditions, and in that light, I have concluded that they were involuntary actions. The latter, at least, came to me like the child to the Virgin – commanded by higher beings.

___

This text was originally published in Spike #76 – An Artist’s Life. You can buy your copy in our online shop.

“Der heimische Waldboden. Höhere Wesen befahlen: Polke zeigen!”

Curated by Bice Curiger

Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin

12 Sep 2024 – 2 Feb 2025