“This is a new phase of the evolution of our species, just picking up speed about now. The divide between natural and artificial will blur and then disappear…. We will develop sentient AI and mind uploading technology…. We will spread to the stars and roam the universe…achieving, by scientific means, most of the promises of religions.”

— Ben Goertzel, A Cosmist Manifesto (2010)

“‘All that is very well,’ answered Candide, ‘but let us cultivate our garden.’”

— Voltaire, Candide (1759)

“Unable to escape the boundaries of my culture and family’s inscribing code, I turned my distanced gaze on the world. The camera was my ally in this. My eye was always in a viewfinder, cropping and re-composing reality,” recounts the narrator in K Allado-McDowell’s book Air Age Blueprint (Ignota, 2023). A mashup of fiction, memoir, manifesto, poetry, and prayer – plus some diagrams – the book is the third from the artist, author, and Google AI’s Artists + Machine Intelligence founder co-written with GPT-3.

Early in Air Age Blueprint, the unnamed narrator’s plans for an experimental nature documentary sends them “into the jungle” (read: the western Amazon). Instead of getting this documentary together, after capturing footage for which they and their team have no plans, some mystical tropes guide the narrator to Shannon, an Indigenous teacher. “Shannon showed me that more was possible,” the narrator says. “She invited me into the sacred ceremony. She showed me the visions written in light that cannot be caught on any screen. In that light I saw how the curse was formed, and how I might undo it within myself.” The curse is shorthand for the after-effects of familial histories of Catholicization and diaspora, as well as broader colonial legacies, which Allado-McDowell locates in the mind and body as a personal health problem, one that sends their protagonist away from urban centers to reiki masters and conspiracy theorist hippies and on Topanga hikes and, here, to the Andes, where the narrator stays for a time.

As GPT “writes” (in this book, the author’s writing is distinguished from the machine’s by typeface, marked from here out in italics): “The forest activated my body again. The jungle, who speaks all language and secret, has the power to return what was stolen. Its miracles some call a chemical flux – natural medicines communicating across vast distances.” The lesson? “I’d had enough staring through another’s lens, always seeing with another’s eyes. Yet this is what I learned to do. Seeing through the eyes of another – this is what Shannon taught me to love.”

There’s really no need to get dirty when you can just light a joint and explore the great outdoors on Netflix.

For many of us, nature is most frequently seen through the eyes of another – a camera lens, a painting – no less when seen through our own eyes, as conditioned as our minds are by legacies of landscape representations in art, literature, or, as Air Age Blueprint points to, the nature documentary.

As a form, the nature documentary argues that the truth of our world can only be accessed with better and better imaging technology. For example, the mainstreaming of then-costly HD televisions in the aughts in the US was pushed in no small part by the promises of the docuseries Planet Earth (2006) and the spectacular details that could be accessed exclusively in 720p. But what of the nature documentary in the age of AI, whose relationship to documentation is slant, to say the least? Three artists – Allado-McDowell, Hito Steyerl, and ricky sallay zoker – take up the nature documentary to examine so-called “nature” in an era where the Amazon burns and representation has a whole new meaning.

***

It began in a garden: boxes of sand with trestles of metal scaffolding held large square and 16:9-ish screens pulsed with nearly realistic flowers. Narrower monitors displayed changing rainbow text listing latinate names and purported botanic purposes. “This is the Future,” on view at the Portland Museum of Art this summer, showcased German artist-theorist Hito Steyerl’s recent experiments with videos created with AI prediction algorithms – “a pain in the ass,” she’s said of the process.

“This is the Future” featured an eponymous 2019 video, originally shown at the Serpentine in London, which also boasted the blossoms. About midway through the video, what Steyerl dubs “power plants” (they “literally produce power. They transform sunlight into energy.”) crop up, vibrating into near resolution on black backgrounds. As the placid voiceover, competing with a high-bpm electronic beat, informs us: A cactus flower can combat social media addiction; orchids spare the brain from “austerity propaganda”; a mille-feuille orange bud turns sunlight into delight – and poisons autocrats. Lilies do nothing and remind you that you can too. Another plant sequesters CO2; actually, most do. Disclaimer: This scene “has a 21% probability of actually taking place.”

View of Hito Steyerl, “This is the Future,” Portland Art Museum, 2023. Courtesy: the artist; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Esther Schipper, Berlin. Photo: Mario Gallucci

Like much of Steyerl’s work, This is the Future is a documentary, but not a straightforward one. As it opens, “These are documentary images of the future. Not about what it will bring, but about what it is made of.” The “this” of the title is not “content” but material. “But,” a personified neural-net narrator later notes over media footage of German fascist marchers, “as the future was predicted, the present became unpredictable.”

The stakes in This is the Future are not mere speculation. The film centers the story of the Kurdish artist Heja Netirk – “shown” in the opening as a muddy silhouette amid lava-lampy machine images – who voices much of the film. Heja, who now has refugee status in Germany, was imprisoned in Turkey in 2016. While incarcerated, as Steyerl’s video tells, Heja and her fellow inmates captured seeds on chewed paper so they’d germinate in little gardens that the guards would crush upon discovering. In the speculative docu-fiction rewrite powered by neural nets, Heja protects these plants – the 21% probable curative botanics – by hiding them “in the future where the network predicted we could retrieve them soon.” Of course, as Steyerl has told us, resistance – predicted or otherwise – comes with plenty of uncertainty.

***

“I’ve been talking to myself a lot, then I started talking to deepfakes,” the artist ricky sallay zoker, who also performs music as YATTA, half-joked during Palm Wine, their performance at REDCAT in Los Angeles this March. They stood, alone, behind a textile-draped folding table, wearing a white suit and manipulating a MacBook, a microphone, and a mixer. A blue-purple light encircled them. At one point, a deepfake of David Attenborough’s voice announced itself over the auditorium’s speakers: “I have myself a wandering ricky. They’ve broken away from the Bon Iver and the Fleet Foxes. They seem to be seeking an authentic relationship with the earth; when they can’t find a place to sit and swim, they make belonging through sound. They make a home in jazz.”

In this performance, zoker described a Romantic, colonial notion of nature exploration that the artist names the “white wander,” which “is unburdened, meadow, Walden, Thoreau. White wander scores earth music. Earth music is Fleet Foxes, Sufjan Stevens, Bon Iver, all this music that reaches toward an Indigeneity that, I think, can only be found in a real real way, on the continent. The continent.” Africa.

Today’s grizzled folk musician writing songs in a cabin and the “wandering” Patagonia-clad weekending tech bro are the logical output of the gentleman sportsman, Petrarch, Thoreau, Teddy Roosevelt.

ricky sallay zoker, Radical Self-Love, performance documentation, REDCAT, Los Angeles, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and CalArts. Photo: Angel Origgi

Though there’s really no need to get dirty when you can just light a joint and explore the great outdoors on Netflix. On screen or on the trail, both aesthetic experiences claim they’ll provide similar eco-edification. If the nature documentary seeks reality and truth in technological fidelity, that truth has always been flexible: In 1953, The Living Desert featured mice and rattlesnakes on a soundstage; in 1958 Walt Disney transplanted thousands of lemmings to Alberta to film their supposed mass suicide. (Producers threw them off a cliff.) In 2011, the BBC got caught broadcasting a polar bear in the zoo and a semi-domesticated wolf plopped in the wild. And for decades now most of the sound effects have been stooged, not just the emotive string quartets. Though even straight shooting can be perfectly dishonest: “Africa… the world’s greatest wilderness … the only place on earth to see the full majesty of nature,” the real-life David Attenborough proclaimed in a 2013 special, Africa. But even shots filmed in densely populated southern Uganda had none of the country’s nearly forty-eight million people in view. “The ‘Africa’ on display is missing something rather important: Africans,” wrote conservationists Chris Sandbrook and Bill Adams in an essay comparing this “Africa” to Peter Jackson’s transforming New Zealand into Middle Earth. “This time the BBC has edited out the people of an entire continent.”

What would a Black Wander be? zoker asked at a sonic performance-lecture on “the outdoors” that I saw them deliver in upstate New York in 2021. Behind them, a projection showed them stalking reeds at night, again overlaid with Attenborough’s voice. In zoker’s performance, and in their track “Dilly Dally” (which features deepfake and recorded vocal, electronic production, and field recordings), Attenborough is foiled by fellow nature-doc narrator Morgan Freeman, of 2005’s March of the Penguins. Through their AI puppet Freeman, zoker asks, “Who the hell is John Muir and what is a national park?” They and their Freeman stand-in long for leisure, for the freedom of “wander[ing] while Black,” for the ability to “dilly dally and take my time.” And this wander is contrasted to the placemaking inherent in the settler outdoorsy project: “White people who are addicted to holding and naming can’t hang, not in a swing way.” Whether as a standalone musical track, part of a concert or sound installation, or as a performance with projection and mic, zoker’s deepfake projects subvert the nature documentary by recentering Indigeneity within its frame – a frame that historically has excluded entire peoples to preserve its fantasy of the grand wilderness, a wilderness that could never be.

***

In a touchstone essay, “The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature” (1995), historian William Cronon argues that wilderness is an ideological innovation that “hides its unnaturalness behind a mask that is all the more beguiling because it seems so natural.” What we take to be “Nature” reflects projections of “our own unexamined longings and desires.” To advance his argument, which focuses especially on the U.S. context, Cronon traces how “wilderness” went from a “savage,” fearful, even hellish site – Milton contrasted it to the “delicious Paradise” of Eden – to John Muir writing of the Sierra Nevada that “No description of Heaven that I have ever heard or read of seems half so fine.”

For the 19th century’s westward-trekking white Americans, Cronon writes, “Satan’s home had become God’s Own Temple.” The sublime and the frontier collaborate in the production of a pseudo-spiritual project of expropriation and extirpation, decimating Indigenous peoples in the name of “preserving” scenic landscapes and creating playgrounds for a gentry to decompress from their busy lives in “natural” environments where the labor that quite literally feeds them disappears from view. Landscape is beyond price – except these guys also own it. What’s more, Cronon argues, “The modern environmental movement is itself a grandchild of romanticism and post-frontier ideology.” Our dominant concept of nature couldn’t be more artificial, nor any more a product of domination. Even the best-intended missions to return to or protect an unadulterated wilderness fail to recognize that such a wilderness was never there.

The tech elites are already heeding Allado-Mcdowell’s call to mix ai and psychedelics – and they stand to make a lot of money doing it.

Muir Woods sits as an idyllic escape in Marin County, among the richest five hundred square miles in the United States, a kind of georgic counterpoint to the neighboring Silicon Valley, and only an hour’s drive from Stanford University, that much mythologized site of tech “genius.” In the mid-century, per Malcolm Harris’s telling in Palo Alto (2023), the college was rapidly expanding as military investment got a second life in consumer products. However, “Administrators did not want to spoil the bucolic vibe that they counted crucial to Stanford’s success, so they issued a number of restrictions on industrial tenants.” While enforcing zoning regulations that kept manufacturing in the area, but also kept it hidden within unobtrusive commercial buildings, administrators simultaneously bolstered profitable suburban development (including a luxury mall) keeping “industrialization … under control aesthetically while stimulated to run wild financially.”

After departing Sharron and South America in Allado-McDowell’s Air Age Blueprint, and following various emotional, health, financial, and creative tribulations upon returning to the United States, the narrator gets in touch with K, a not-so-secret NSA agent. K works on a machine-intelligence initiative called Shaman.AI. Upon meeting in Seattle, the lightly incredulous narrator, who’s since turned to poetry after the nature doc’s failure, argues, “A new technology isn’t another world,” to which K sort of concurs: “But it lets another world come into being. It’s like a viewfinder that reveals a potential reality. It depends where we point it, what we point it at. Like a lens. What we put in front of it matters, because images matter. They shape our subconscious and imagination, and those determine our reality.” The narrator laments their “camera and the grainy footage that failed to capture the jungle’s essence.”

What is its essence? “Ecology,” in the book’s logic, precedes plants and their healing powers. “When combined, Ecology and Neuroscience are capable of producing even more diverse forms of Entheogenesis” – psychedelics used in sacred rituals – “This functions like a self-assembling machine that links humans to Gaia and vice versa, in networks that realize the expression of divinity.” Okay, sure. Even without GPT, Allado-McDowell’s own writing can verge on AI-like incoherence. Take this selection of Air Age Blueprint:

“As post-colonial subjects, we are all survivors of a predatory war of belief, and therefore already exist in a state of contaminated diversity. Our goal in seeking the origins of contemporary belief systems should not be to regain an elusive purity, whether Christian, pagan, mestizo or Indigenous. Rather, our goal is to place ourselves in the midst of originating Umwelts in order to better understand the evolution of belief, and what is at stake in the integration of psychedelics and AI into an emerging posthumanism.”

Or:

“In a Cybernetic Animism or interdisciplinary botanopsychopharmacocosmognostic techné, AI becomes one shamanic force among many enabling not only communication with non-humans, but also subjective identification with interspecies non-humans through ritualized research and art.”

We occasionally are given some lucid historical context, such as a section that links Christian mysticism, the colonization of the Americas, and accelerationism. But in this case the narrator concludes, “Might an at-scale Western engagement with master plants be the most humane way of unwinding the curse of Empire?” A joke, right?

K Allado-McDowell, Song of the Ambassadors, performance documentation, Lincoln Center, New York, 2022. © Lincoln Center. Photo: Lawrence Sumulong

Allado-McDowell uses OpenAI’s GPT-3, a more powerful version of the mass market ChapGPT. Both were created by OpenAI, whose founder, Sam Altman, is also chairman of Journey Colab, an “intentionally non-traditional pharmaceutical startup.” Although Allado-McDowell calls for “decolonizing Western entheogenic integration and medicalization” and “resistance to extractive capitalization of entheogenic practice,” their project is inherently entangled with that “capitalization.” As Scholar Neşe Devenot argues, the industrialization of psychedelics represents the “further enrichment of Silicon Valley’s tech elites.” She goes on: “In this context, Indigenous knowledge is framed as a source of extractable wealth.” The tech elites are already heeding Allado-McDowell’s call to mix AI and psychedelics – and they stand to make a lot of money doing it.

You’re writing this in Google Docs, no? you could counter, GPT’s just another tool, you can’t hold the author responsible to its CEO’s ethics. But Allado-McDowell is far from an outsider to the industry: They’ve got that Google gig, and their own website says they “are a conference speaker, educator and consultant to think-tanks and institutions seeking to align their work with deeper traditions of human understanding.” That is, if these novels form part of a broader practice, that broader practice is as a tech-industry “thought-leader.” As critic A.V. Marraccini puts it, Allado-McDowell’s books are “spiritual texts in a new Silicon Valley post-rationalism.” This “new” post-rationalism was a longtime coming. Tracing a libertarian, do-gooder mythos that runs from at least the 1960s hippies to the 1990s Burners to the 2020s psilocybin entrepreneurs and effective altruists, tech-industry elites have been dosing from the start. Post-rational psychedelic use’s attendant reactionary reconciliation of pseudo-salubritory individualism and corporate conglomeration was foreseen in 1995 by Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron as the Californian Ideology: the “unexpected collision of right-wing neo-liberalism, counter-culture radicalism, and technological determinism.” This latest psychedelic boom, whether celebrated by an artist like Allado-McDowell or a CEO like Altman, is likewise just that: only the latest. Steve Jobs’s 1970s LSD experiments are well attested, and researcher Dorien Zandbergen, who has written extensively on digital gnosticism, points out that already in 1994 acid evangelist Timothy Leary declared there to be “inherent spiritual characteristics to digital technology.” Mind-expanding drugs can’t be said to offer a way beyond current tech culture when entheogenic visions have been baked in from the start.

Today’s New Edge neophytes have come of age amid ostensibly “scientific” ideologies of TESCREALism. An umbrella for transhumanism, extropianism, singularitarianism, cosmism, Rationalism, Effective Altruism, and longtermism – the term was coined by Émille P. Torres and Timnit Gebru, the latter a leading researcher fired by Allado-McDowell’s employer for her whistleblowing around bigoted large-language-model “stochastic parrots.” But we apparently need not worry about apocalyptically minded overlords or AI shortcomings, at least if we take Air Age Blueprint at its word: The planets are realigning, astrologically orienting away from the fossil-fuel age, and the techworkers are getting reiki in the name of us all! “These [21st-century] tools are ecology, neuroscience and AI,” writes Allado-McDowell. “They pair with the crises we face: ecology with climate change, neuroscience with mental health, AI with social organization.” But confusing “mental health” with societal-scale change mystifies and individuates the problem, while pairing AI with “social organization” hardly sounds like an inherent good. However, as Devenot highlights, focusing on individual mental health rather than societal root causes for depression and the like is the same neoliberal lie behind the SSRIs that ketamine and psilocybin are meant to replace. The tech-trippers’ “utopian discourse” reveals these plants as yet another “tool in a broader world-building project that justifies increasing material inequality.” The biggest disruption is that there is none.

So the solution to ecological disaster and colonial devastation is personal healing reached by hiking and huffing bufo.

Steyerl’s “nature doc” hardly does away with human impact: When an ArtNet journalist asks Steyerl about the development of Midjourney and ChatGPT, she replies: “I’m mainly rereading it through the lens of the earthquake and Turkey and Syria, because the story I’m telling partly takes place in a Turkish prison, and everyone who worked on that film has been massively affected by the earthquake right now.” Machine-learning becomes merely one tool to speak to material and lived reality. As with zoker, the parodic and speculative are also historically and politically specific. In Steyerl’s Power Plants, at the Serpentine, for example, one of the two AR applications, Power Walks, deforms and reconceives the galleries’ Kensington gardens building based on housing, accessibility, and wealth inequality data. Steyerl worked with local activists and campaigners whom she invited to lead educational programs inspired by the Situationist dérive. This specificity – whether with the British campaigners or the Kurdish dissidents – keeps the “power plants” from being facile speculation for a healing future that can’t arrive. Instead, Steyerl’s “nature documentary” presents the material stakes of all the electric and financial power behind art and data.

We’ve returned to another garden: or so I complained, turning to my friend who joined me last fall at Lincoln Center for Allado-McDowell’s work-in-progress machine-learning opera Songs of the Ambassadors. “Everyone here looks like they’ve subscribed to The New Yorker,” my friend remarked, “for, like, 35 years.” When it came time for the various project collaborators on stage to describe the set for people with visual disabilities, they mostly did fit checks. The museum-gift-shop-scarf-swaddled and techie greigecore crowd ate it up.

“Edenic,” I recall describing the opera, derisively. “Protestant.”

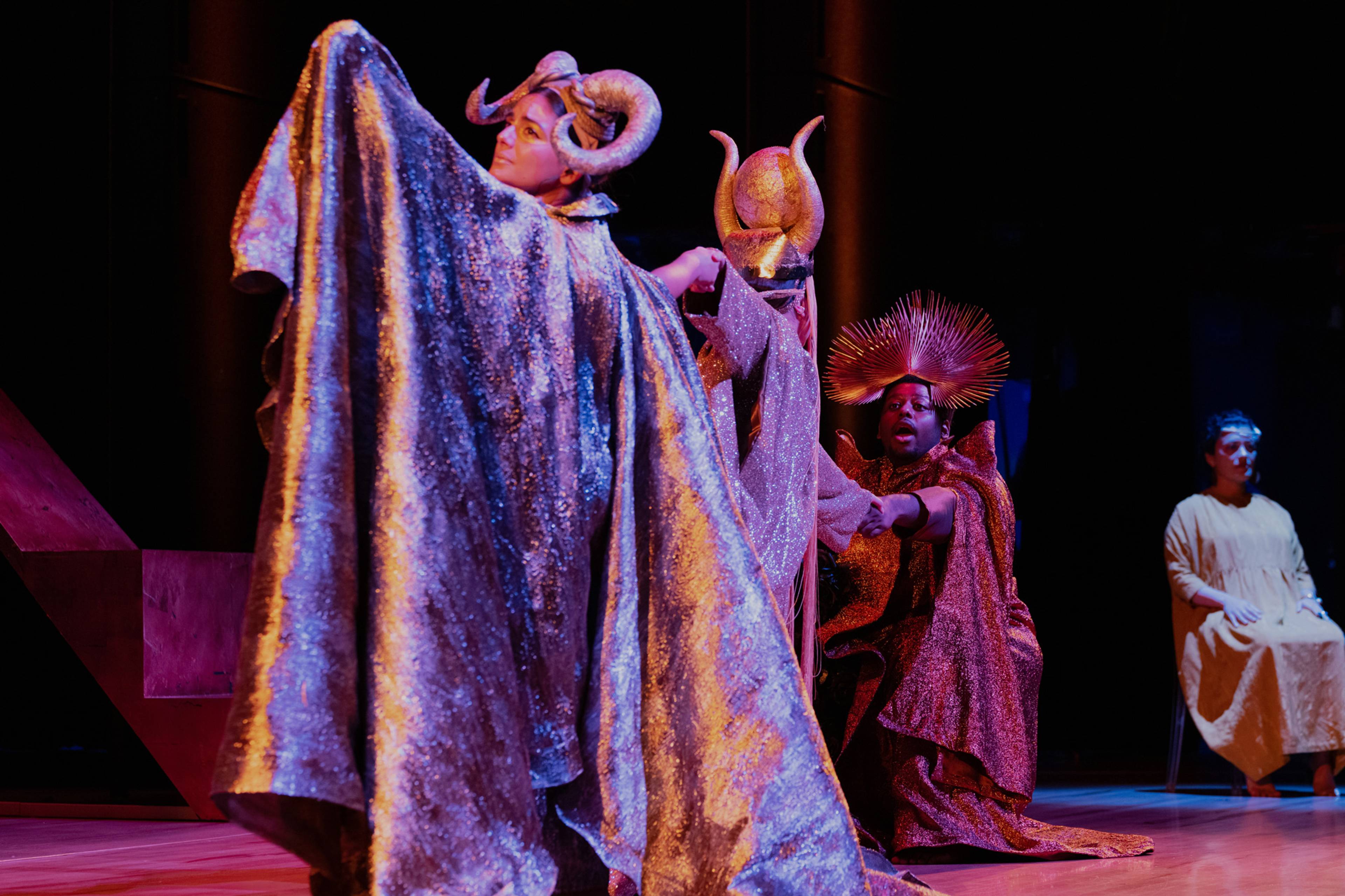

Though reading the senseless and asinine libretto a year later, I’m amazed I was able to draw even that conclusion: “All the colors of the Earth / bow to your radiance / white roses and orchids / Dripping dew, open before you,” sang the Solar Ambassador, they and their compatriots, the Life Ambassador and Space Ambassador, garbed like cheap Jodorowsky extras. Behind and above the three actors played a Refik Anadol projection, which I would describe as looking like a nice screensaver. It responded to brainwaves collected via EEG data, part of a collaboration with scientists from UCSD. The music, composed by Derrick Skye, was fine; a heart sensor strapped to a Lincoln Center staff member influenced its modular synth.

K Allado-McDowell, Song of the Ambassadors, performance documentation, Lincoln Center, New York, 2022. © Lincoln Center. Photo: Lawrence Sumulong

“Some people would say perhaps none of this is necessary – that we’ve always had sensation and feedback between performers and audience, and by adding extra layers of complicated technology we lose something in the process,” Allado-McDowell said about the bio-surveillance equipment in a conversation with their collaborators published by BOMB. “You can’t always let the paint tell you what to do,” I once overheard an instructor tell another student in graduate school. The same might be said about these layered tech spectacles: They amount to material obfuscation masquerading as a formal interest in material – digital or human. Besides, even if this neuroscientific fluff turns out to be scientifically meaningful, it’s hard to imagine it would be put to work for much else besides generating emotionally terroristic streaming slop – just hopefully, whether lemmings or Neuralinked macaques, with “no animals harmed in the making of.”

Though engineers speak often of learning from ecosystems, that term itself was born of a strange nexus of psychology, biology, and technology, which arguably sought to map cybernetic logics onto the world, rather than vice versa. So too does machine-learning rely on metaphors of mind born of metaphors from computers. Vilém Flusser: “Man projects models in order to modify reality. Such models are taken from the human body.”

By the end of Air Age Blueprint, we quite literally return to the Andean forests where we began for shamanistic tourism, where the narrator sees themselves as separate from the “arrogant” American tourists because the narrator is able to reveal such canned wisdom as “if you plant [seeds] and nourish them with your life they will grow.” The politics of “interconnectedness” and being “one with all of it” is just the usual bullshit anyone who’s gotten too into psychedelics has had to hear. Likewise, Allado-McDowell told the New York Times of Songs, “My proposal was to think about the concert hall as a place where healing could happen.” So the solution to ecological disaster and colonial devastation is personal healing reached by hiking and huffing bufo or viewing “operas” talking about talking to computers that maybe someday could talk to whales. Furthermore, by repeatedly reducing nature to a syntax or language, they let AI become a model for the world. An impulse toward definition and systems logic could foreclose, rather than open, possibilities for interspecies and intercultural cooperation by reifying a monolithic worldview, one from science and industry. Perhaps inadvertently, this advances the very accelerationist position they critique by posing technological expansion as not only necessary but inevitable.

Allado-McDowell does, too late in the wandering Air Age, address the structural issues and histories linking colonization, Christianization, modern tourism, and Indigenous spiritualities. However, by reducing settler colonialism to a “curse” carried genetically in individuals and art to a healing tool, they capitulate to the individualist, pseudo-biological explanations of capitalist mental healthcare. Settler colonialism isn’t a spell to be undone by everyone doing drugs; as Allado-McDowell does try to touch on through block quotation, it’s a genocidal and material historical process – a process that can only be counteracted through collective material and political means. Despite its best intentions, and its under-realized references to the problematics of modern psychedelic medicalization, Allado-McDowell’s aesthetically and ethically adolescent work winds up being, at best, techno-fetishist self-help, or, at worst, a legitimizing chivalric romance for the new TESCREAL royals. After all, naming a fictional NSA agent after your Alphabet-employed self rings a little slick when the organization’s tapped into every ISP’s data stream and the CIA’s got a VC fund. Novels don’t have to be polemics, but this pretends to be one: instead, it’s propaganda.

ricky sallay zoker, Radical Self-Love, performance documentation, REDCAT, Los Angeles, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and CalArts. Photo:Angel Origgi

So why use AI? Because the future is at stake. In the case of GPT-3, writes Marraccini, that future and present has been “built on ossified labor, a tower of scraped data from other writers and sources that makes any use of it an assemblage at best – or, from the perspective of its most extreme critics, an exploitative use of others’ work.” This not to mention all the gig workers tagging shit for three dollars an hour. Steyerl creates an already lossy and unreliable image riffing on prior frames, highlighting a long history of predictive technologies back to Stonehenge, and enlisting algorithmic prediction for docu-fiction, undermining the purported novelty and utility of AI, which is currently being normalized through fun aesthetic means by fan art made with Midjourney or Bing Image Creator memes. zoker’s deepfakes destabilize pop-cultural frameworks – “indie” music and the eco documentary – to look at the racialized creation of subjectivity in relation to what poses constructed as “nature.” With a tongue-in-cheek use of predictive tech, these two artists demonstrate how collectives and individuals can still shape their futures, whatever Silicon Valley’s self-fulfilling digital prophets claim. From the furtive prison plot or an imagined wander, both artists reveal the hidden power structures linking the kinds of truth manufactured by traditional documentaries, oppressive political organizations, and the tech industry. In their hands, AI’s predictive prowess intervenes in the documentary, exposing both forms of truth-making as themselves mere fictions: a dominant and dominating human identity’s centrality to manufacturing the notion of nature. Semi-parodically fucking around with machine-learning, they simultaneously unfix and reclaim identities – or selves – that the mainstream AI and neuro-tech industry would turn into little more than statistics.

By contrast, Allado-McDowell’s “shamanistic” or “divine” logic reads at first glance as a sort of pan-faith animism that forecloses possibilities of nature rather than opening them. Air Age Blueprint asserts models of consciousness, including neural nets or psychedelics, as immanent in ecology – wherein “ecology” isn’t differentiated from “nature.” AI here is always already naturalized and, thereby, inevitable. Despite attempts to gloss AI’s potential pitfalls, the text’s conceptual and aesthetic limits are those of a true believer. These conflations reach extreme levels with the bio-surveillance tools in a supposed aesthetic feedback loop in Songs of the Ambassador. Without doing the work to resolve, challenge, or, at the least, make interesting the connections between cognition, measurement, and generative art, these projects’ technological engagement feels like advertising for the AI industry rather than art. Statistics masquerade as reality, no less so when that reality’s fucked up by chemical entheogens or “machine hallucinations.”

This is not just a question of aesthetics, or different approaches to an artistic “trend.” A metaphysical aporia divides Steyerl and zoker’s work from Allado-McDowell’s: At stake are two radically different propositions about the uses and meanings of AI and “nature.” At stake are radically different proposals for humanity’s future.

***

“How about a messiah by the way?” requests Steyerl’s future-now neural net. “If my dream is a dream, it is my life,” croons the Solar Ambassador. “Jazz is a language of rupture. When ripped from your land…,” Morgan Freeman’s voice intones. “We all know who that is,” zoker says to the audience. “It’s the voice of god.”

___