“In the dark times/Will there also be fashion?” to paraphrase Bertolt Brecht (or possibly one of the girlfriends who “helped” with his writing): “Yes there will be fashion/About the dark times.”

There is no doubt that we are in dark times, from which fashion is not excluded. What has been called the culture wars has also become the couture wars. As the US government’s assault on trans and female bodies continues, it’s difficult to ignore how Trump’s “two-gender policy,” introduced this January, works with traditionally gendered dress codes.

Gender-inflexible dress has always been a weapon of control, especially at work. In 2017, Trump reportedly demanded that his female staff “should dress like women,” prompting a #DressLikeAWoman social media backlash in which women posted selfies wearing a variety of professional garb. In 2019, his administration filed a brief with the Supreme Court that would effectively ban visibly trans people from the workplace arguing that Civil Rights Act provision “does not bar discrimination because of transgender status.” Aimee Stephens, a trans woman who was fired in 2013 for refusing to wear “male” clothes, fought back, and the Supreme Court ruled that discrimination against LGBT employees was illegal. Stephens’s name was added to the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor at the Stonewall National Monument – but this year’s two-gender policy threatens to bring it back.

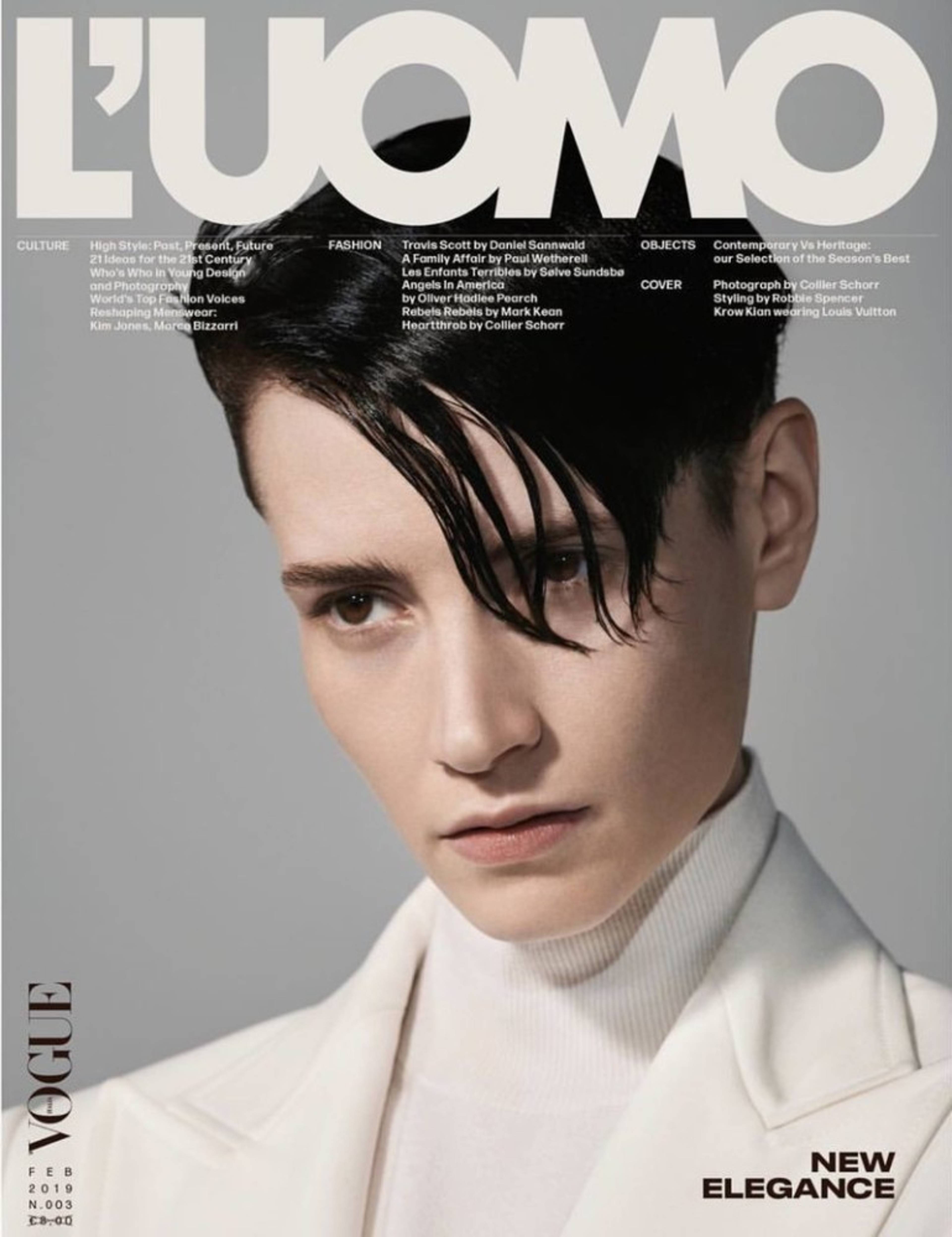

Krow Kian was the first transgender model to appear on the cover of L’Uomo Vogue (2019) in the magazine’s 50-year history.

In 2024, the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show featured its first trans models, Valentina Sampaio and Alex Consani (pictured here).

It also evokes the notorious late 20th-century “three-article” rule, based on masquerade laws that prohibited “costumed dress.” Used by the police to check people for clothing that didn’t correspond with gender assigned at birth, it allowed them to identify and arrest non-conformers, which prompted the five-day-long Stonewall “riots” protest in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1969. (Funny how this law was used to check urban clubs like the Stonewall Inn, rather than, say, rural women wearing “men’s clothes” for farm work.) In February 2025, the Trump administration removed the word “transgender” from the Stonewall National Monument website, as well as other government sites.

Gendered dress can work a bit like French philosopher Louis Althusser’s “interpellation,” which describes what happens when you respond – verbally or not – to a call of Hey, you!, offering yourself up for recognition as that kind of person. Althusser’s interlocutor is a representative of state control: ultimately a police officer. If you respond to the call, you submit to the state’s power. Or, at least, acknowledge that you’re willing to place yourself in some sort of relation.

But interpellation does not usually rely on an outright rule of law, just as Trump’s insistence on “feminine” dress was not a rule but a powerful suggestion. When getting dressed, interpellation is never only an option: there is no neutral ground, no way to refuse to respond. Leaving the house naked is so unusual as to be a positive choice, meaning that making a fashion statement is something everyone does – helplessly. Like all language, this declaration is not always voluntary. You can be constrained in what you can say by the ways you have been taught to speak – by what you consider acceptable in the situation, by consideration for others, by limited time and limited resources, by the implicit rules of gender, race, class, by the explicit rules of your job, or the rules of appearing as a subject in public, the rules of the state.

There is no doubt that we are in dark times, from which fashion is not excluded. What has been called the culture wars has also become the couture wars.

If fashion works like language, finding a name for a look is a powerful political tool. In 1970, the American writer Tom Wolfe coined the viral phrase “radical chic,” which he used to suggest the corruption of activism anytime it could be categorized as “fashion.” “That party at Lenny’s” was a glamorous upper-East Side fundraiser held by Leonard Bernstein and his wife, Felicia, for the black power group Black Panthers, sharp-dressing members of whom had – Wolfe believed – been invited as a kind of woke fashion accessory. Wolfe’s idea that play with dress codes is not only unimportant to radical politics, but undermines them, cuts any agency from the activists themselves. As Ben Davis pointed out in Artnet (2020), Wolfe’s coinage was “an implicit attempt to split two things apart, politics and style – that activists actually work hard to bring together.”

An insistence that activism dress down is not only its own particular form of oppression but ignores the deliberate nature of the sartorial choices that also hold opposition groups together. Nothing is stricter than a right-wing dress code, and fascism will always come to the party correctly dressed. The US’s self-proclaimed “Trumpettes” are a female-run fan club who, like Leonard and Felicia Bernstein, use parties and other social platforms – online and off – to network their politics. They have an easily recognizable and strictly gendered look: high-femme, highlighted and – yes – a little bit orange. This ties in with the “boom boom” trend, which – according to Sean Monahan, one of the people who brought us “normcore” – is greedy, shameless fashion that also invests heavily in traditional gender norms: high heels for girls and square-shouldered suits for guys. But what its wearers can’t control is how these codes are played and replayed, particularly through those twin towers of interpretation: kitsch and camp.

Raúl Lopez’s label Luar plays with conservative femme dress codes during FW25.

If kitsch is a sincere, commercial imitation of a high-end look that’s directly or indirectly unattainable (not only the designer prices but the upkeep: the dry-cleaning, the hairdressing and exercise necessary to maintain that kind of look), then its reification is a crucial stage in camp. A loving look at what kitsch reproduces cheaply, camp acknowledges a double distance from the original by according value not to the designer version, but to the dedication of those who buy into the kitsch imitation. In doing this, camp detaches something of the spirit of the original from its expression, and queers it, so that the essence of style relies less on straightforward glamour than a kind of play that incorporates its own distance from that glamour, in a radical acknowledgment of vulnerability.

The kind of interpellation that camp enacts is not a call for response by structures of power, but an appeal to mutual recognition via its act of détournement. If fashion can’t change the world alone, it can, at least, in the dark times, let us show each other we’re still alive.