I’m at the airport when he catches my eye: 50s, graying, Canadian tuxedo featuring a Carhatt denim work jacket, round steel specs, he wouldn’t be out of place on Derek Guy’s Die, Workwear blog. In his milieu (I’m guessing he’s anything from a cabinetmaker to a Shoreditch restauranteur), he may fit in. Here, he stands out. Because he looks so perfectly himself, or what looks to be perfectly himself. And at the airport, that’s so rare.

There’s nowhere people look so much themselves as when traveling. This is because transport is public. Drive your own car (or private jet), and your look is lost. But there’s also no other place people look so much like someone else. This is because fashion is so often not about who you are, but who you’re not; not about where you are, but where you’d like to go. This is why dressing up for travel used to be a thing. Being a member of the gig economy, I don’t exactly take holidays, and I don’t dress for them. In mid-20th-century Europe, with air travel still rare but newly accessible, passengers dressed as if for a job interview. They wanted to look smart. This was only just after a war during which travel was – except for the very rich – a misfortune.

These are not urban tracksuits; they’re nostalgia for an age when leisurewear accessorized leisured travel and when travel – for the privileged few, at least – was itself a form of leisure.

2024 is the year of “revenge travel,” with post-lockdown tourism so overwhelming that residents in Barcelona have resorted to a water-pistol campaign against mass sightseers. And this is the year of fashion show as holiday. While Chanel was rained off in Marseille in May, Jacquemus was guaranteed Capri sun in June, filming his models boating across the bay to the show, travel as catwalk.

But, even on holiday, fashion never relaxes. It’s so difficult for fashion to do nothing. Even at leisure, it’s busy assembling the right clothes. Often referencing organized sports like tennis or yachting (boat shoes are the shoes of the season), they displace the wearer not only in (for most people) class, but in time. These are not urban tracksuits, they’re nostalgia for an age when leisurewear accessorized leisured travel and when travel – for the privileged few, at least – was itself a form of leisure.

If travel is displacement, then so is fashion, and that’s where it runs into problems. The thing about travel dressing is it always isolates you not only from the people you’re traveling with, but from the people in the place you’re going. A regular dodgy fashion story in mags I bought as a teen showed white women in western clothes – often pale linen and straw panamas that queasily referenced colonial dressing – hugging groups of smiling locals of color. Dolce & Gabbana ads still feature tall, sleekly dressed models contrasted with bands of tiny, black-clad Italian grannies. Now, D&G may love their nonne, but there’s no doubt that the older women are not “in fashion,” in an environment where fashion confers subjecthood. As older, traditionally dressed women, they are landscape. They function literally as “local color.”

Dolce & Gabbana 2015 campaign

What could be done to change this take? A couple of years ago, I went to the Cartier-Bresson x Martin Parr show in Paris: photos of contemporary and 1950s British holidaymakers. One film made by CB had a hilarant French voiceover that chortled at the 20th-century English on the beach in suits. Truth was, these northerners (amongst them, perhaps my grandparents, catching their yearly break from work in Lancashire’s paper mills) didn’t have special clothes for travel. They’d unbutton their jackets and roll up their trousers and – yes! – sometimes deploy the famous knotted hanky for a sunhat. While Parr’s photos find vulgarity – lobster tans, the loud print and louder food – Cartier-Bresson’s catch what he called “the decisive moment,” which should have been called the “decisive movement,” an unplanned gesture, so delicately and sympathetically caught, that marks the subject out as an individual. Parr’s photos make everyone part of the crowd; Cartier-Bresson’s give each dignity as a person.

The problem with travel fashion is the problem of the Other, which was also the problem for 20th-century theory, that has leaked into the 21st century from psychology (where it stands for a range of ambivalent structures that contextualize the self), to post-colonial studies, where it’s defined as an almost universally negative method of objectifying those subject to colonial rule.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Blackpool, juillet 1962 © Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos

So, what to wear for travel that neither objectifies nor appropriates? Maybe what you’d wear at home, adapted to your destination’s weather. The historian Achille Mbembe, in his essay on the work of Franz Fanon, Necropolitics (2019), described the passant, or passer-by, a post-colonial subject whose identity, rooted in their own geographical heritage, is only fully revealed when, displaced by migration or travel, they have a genuine and reciprocal “recognition” of the Other. This “figure of a human out to make great strides up a steep path – who has left, quit his country, lived elsewhere, abroad, in places in which he forges an authentic dwelling, thereby tying his fate to those who welcome and recognize their own face in his, the face of a humanity to come,” looks for similarities, rather than difference: “No mutual recognition arises without a claim about the Other’s face being, if not similar to mine, then at least close to mine.”

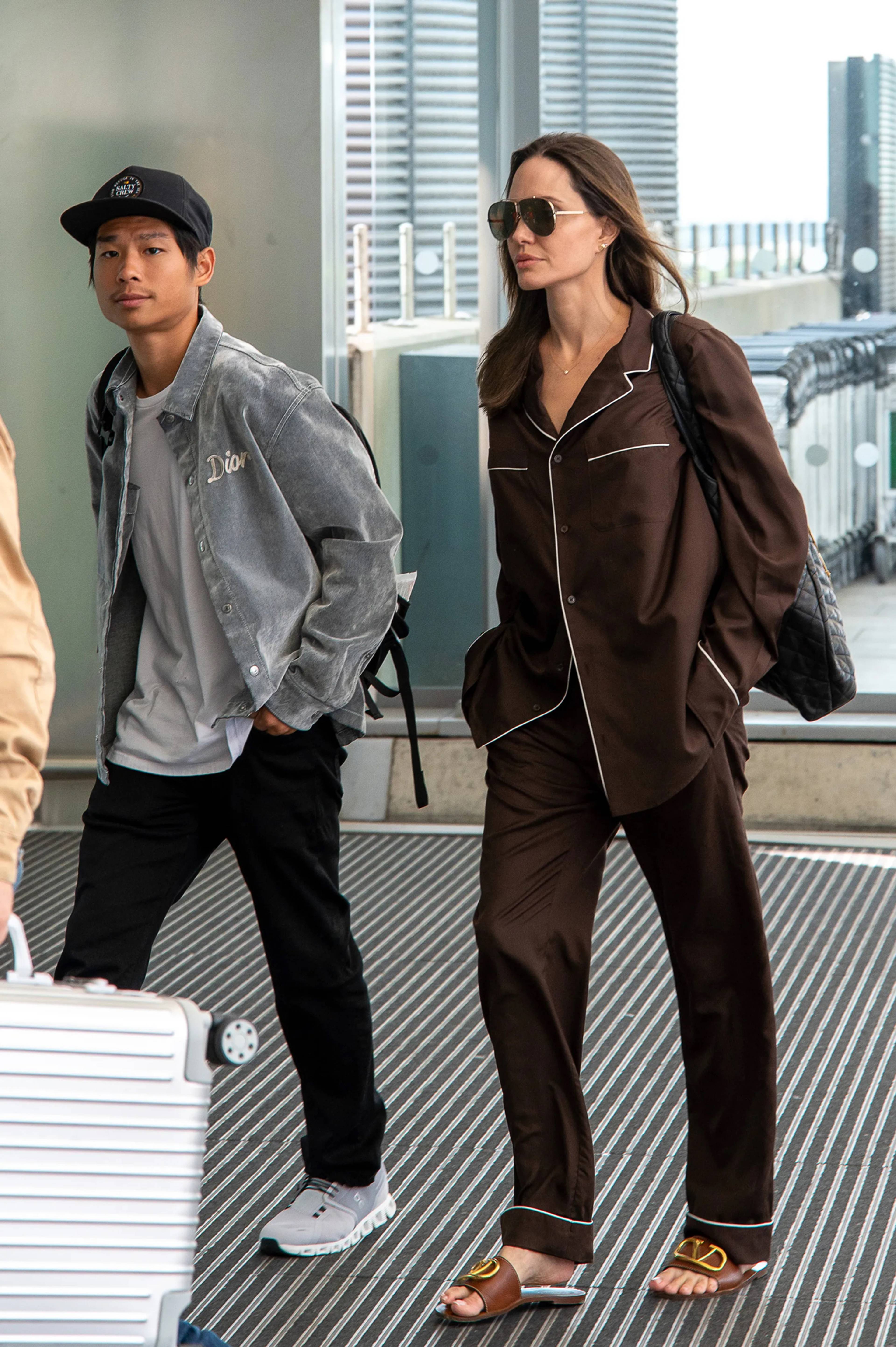

Now, the way to dress at the airport is not only as though you haven’t left home, but as if you haven’t got up. Contemporary airport dress is loungewear: not as in airport lounge, but as in lounging on the sofa. Birkenstocks, slouchy socks, travel pillows, tracksuits (ideally cashmere), have little to do with more traditional kinds of holiday activewear, and nothing to do with the destination. This is travel as an end in itself. This is also magical thinking. If, as Robert Louis Stevenson wrote, “to travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive,” then “hopefully” is key. Both fashion and travel are predicated on hope, but, as travel has become more stressful (security theater, no-frills budget flights, post-lockdown staff shortages), why not pretend that travel is such a comfortable, enjoyable experience that you feel you’ve never left home at all?

Angelina Jolie wears pajamas to the airport, 2022. Courtesy: Splash News

___