“Am I a snob?” asked Virginia Woolf in front of the changing room mirror as she tried to choose an outfit that would allow her to fit in with her posh friend’s chums. When I first read her essay as an undergraduate, any meaningful class distinction between the monied Woolf and her even more monied mates was scarcely imaginable, and even less relevant. Rich people wore luxury clothes. That was that.

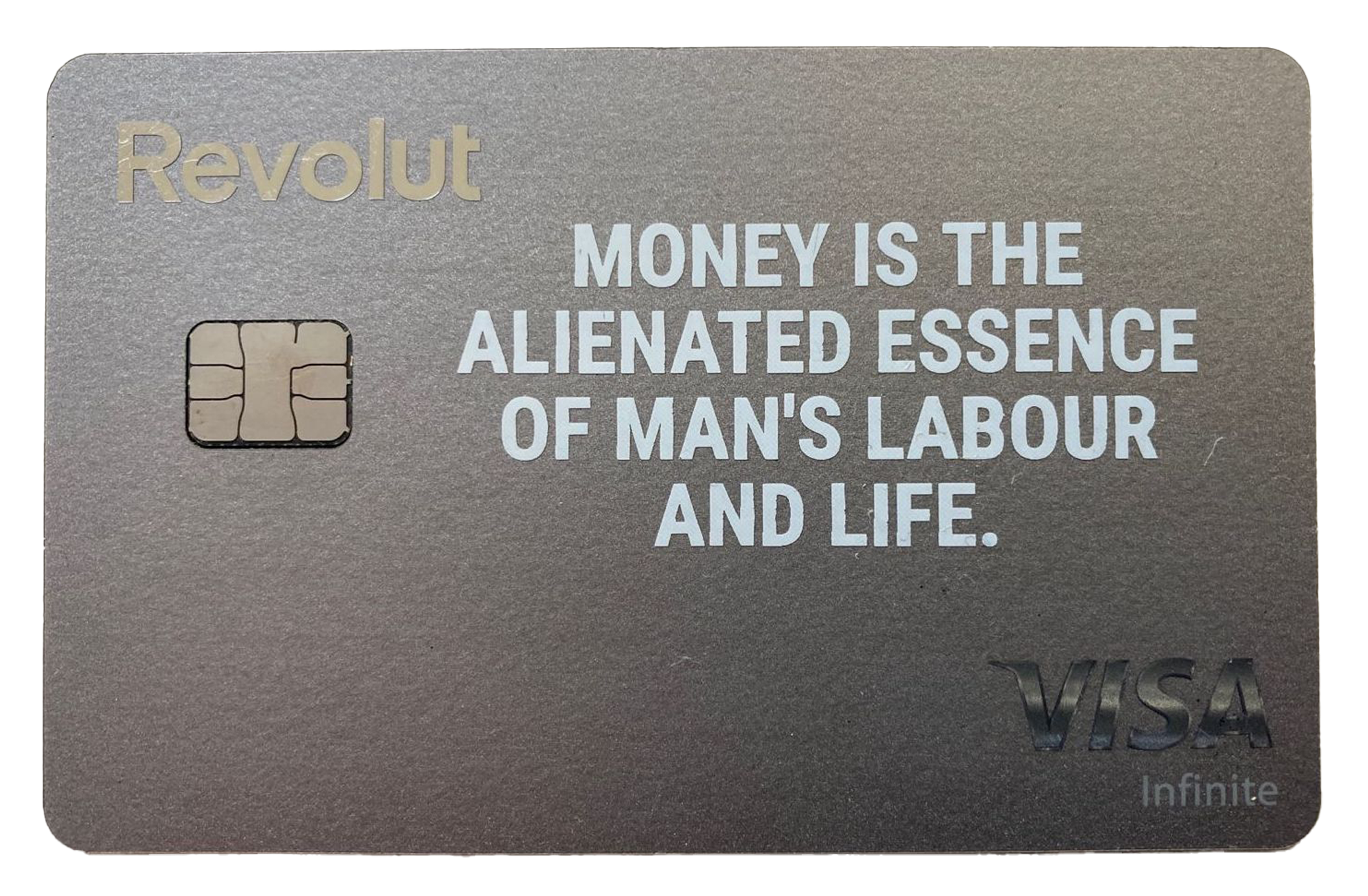

A luxury item adds “class,” simultaneously suggesting a distance to be crossed between a classy garment and the person rendered “classy” by it. Is luxury style or quality, or just a “tell” that this garment is associated with “thequality,” (a.k.a. the classes that are called upper) and might promise a similar life, or imply the wearer has it already? Now I wear tweed and cashmere (if second-hand). But, as a card-carrying Marxist,* can I have luxury without class?

*The writer is literally a card-carrying Marxist after her bank gave her the opportunity to customize her debit card.

“Clothes wear us,” wrote Woolf in her novel Orlando: A Biography (1928) “and not we them.” Besides being a work of gender performance, the book is, as the critic Angela Carter called it, “an orgy of snobbery,” “the apotheosis of brown-nosing,” and “a slobbering valentine to the upper classes.” There is the point at which class meets “classiness,” which is a gendered adjective. A luxury look usually leans hard into gender or flaunts the gendered uniforms so many of us are obliged to put on every day for the kinds of work that signal our lack of access to a luxury lifestyle. Take the gendered luxury in yuppie conspicuous consumption movies, Pretty Woman (1990) and Working Girl (1988) (themselves interchangeable titles: Working Girl has also served as a synonym for sex worker). There’s that scene in Pretty Woman where Julia Roberts uses her newfound wealth to throw shade at the snobby saleswomen in the luxury fashion store, who don’t find her look classy enough for their product: “You work on commission, right?” she asks, after being told to leave and returning with an armful of Chanel carrier bags. “Big mistake! Big! HUGE!” Or when working-class Working Girl, Melanie Griffith, shows off the relatively quiet luxury dress she’s borrowed from her WASPy employer. “Six thousand dollars? It isn’t even leather!” Wails her friend, Tess, played by Joan Cusack, after spotting the price tag.

“A dress becomes really a dress only by being worn,” Karl Marx wrote in A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859). And, I’m sure Marx knew, it all depends on who’s doing the wearing. The drag worn by black and latinx queens in Jennie Livingston’s 1990 New York documentary, Paris Is Burning, is as much economic and cultural as gendered. It’s not about being just any girl but that girl, the girl at the intersection of financial and racial privilege. “I would like to be a spoiled, rich, white girl. They get what they want, whenever they want it,” says house mother Dorian Corey. The queens made the movie famous, but other ball performers competed in the strictly masc-on-masc drag of class-ridden luxury: in pinstripe executive suits and yacht-club-blazers, correct down to the smallest detail. One masc-dragged ball contestant is disqualified, suspected of wearing a woman’s mink coat, and exits frantically yelling, “It buttons on the right!”

Luxury in fashion isn’t really about clothes at all. Quit saving for cashmere. Luxury is about looking like you have those nothings that are scarcest under capitalism: time, and health.

What makes that scene funny is the moment the contestant was forced to speak. Real luxury is when the clothes do the talking. I’m not sure what to make at the recent trend for quiet luxury, which suggests less a rich person than a caricature of one, all cashmere and pearls. It’s the kind of conservative look that Roberts’ Pretty Woman asked for in the snobby boutique, and that appears under frequent “clothes that make you look rich” headlines on Whowhatwear.com, which is not a site aimed at a luxury readership. I find the look worryingly conformist for anyone who doesn’t have the big stick of real wealth to back up its soft, covered-up contours, seemingly designed to make women look unthreatening. This is why, no doubt, it was the vibe of Gwyneth Paltrow’s 2023 court appearances in which she had to look like the sort of person who wouldn’t run someone down on the ski slope. Real rich people, or the few I’ve known, tend to give less of a fuck about luxury because, for them, garments are not aspirational. As they don’t need to instrumentalize their clothes to achieve anything, their looks often range from frumpy, to kind of crazy. When fashion doesn’t serve social mobility where does luxury go? And now that quiet luxury is reproduced by every chain store that stocks a knitted co-ord in tones of sludge, what clothes are really “luxe”?

If, as union leader Big Bill Haywood said, “nothing is too good for the working class,” after being told his fancy cigars were out of line with his political position, let’s flip it: nothing is too good for the working class. Luxury in fashion isn’t really about clothes at all. Quit saving for cashmere. Luxury is about looking like you have those nothings that are scarcest under capitalism: time, and health. You can get the Sporty & Rich look without being rich. Buy a shell suit and a pair of tube socks. Mix them up with a retro blazer and merino knit. And don’t just wear them for sport. The real luxury here is not the clothes but the body they showcase in their photoshoots: tan skin, toned torso, straight teeth. New Balance is a little more interesting, if still relentlessly Upper East Side. Aimé Leon Dore x New Balance’s 2020 classic (and, yes, very charming) ads show seniors wearing tweeds, layered with sweats, like eccentric millionaires, finished with the eponymous sneakers.

Aimé Leon Dore x New Balance ad

Aimé Leon Dore x New Balance ad

The myth that old clothes are a non-luxe option is related to the myth that it’s stylishly “thrifty” to wear (with irony) your grandmother’s pearls or your grandfather’s tweed jacket, both of which suggest you’re not the sort of parvenu who, as UK Conservative politician Alan Clarke said of a colleague, “had to buy his own furniture.” Vintage used to be a luxury. Before the recent explosion of Depop and Vinted, it involved not only the luxury of being able to wear what the hell you like, but having time to trawl thrift stores for gems, not to mention the luxury of living in (or knowing about, and being able to travel to) a zone where those stores stock silk rather than polyester.

Now that any savvy internet-user can thrift cashmere online, the “mob-wife” aesthetic is backlashing quiet luxury, the more obvious, the louder, the more expensive the better. Between November 2019 and February 2022 the US price of Chanel’s immediately recognizable Medium Flap Bag increased by 60% and, in 2023, Sotheby’s auction house recommended investing in the bag alongside antiques and art. Is luxury fashion fuelling economic division, or just reflecting it? According to a 2023 Oxfam Survey, extreme wealth and poverty have increased simultaneously for the first time in twenty-five years, even in developed countries, with the top 1% of wealth holders in the UK as wealthy as the bottom 70%. Now that luxury logos are out of the reach of anyone but the hyper-rich, there’s no need to be quiet about it.

While you’re unlikely to find a bargain Chanel bag in an Oxfam shop, if luxury fashion pricing is a reliable indicator of the distribution of wealth, then the measure of a more equitable society might just be a more affordable Chanel bag.