I ordered a jacket from Vinted. It wasn’t what I thought it would be. It was clearly the jacket on the photo, and the quality couldn’t be faulted. But the fabric was thicker than I’d imagined; it was less of a blazer than a coat. And the cut was bigger, boxier than the image suggested. Re-sell? Maybe not. It wasn’t “me” but it looked… good.

My friend, the artist Isabella Streffen, says that no one looks so good as when they look most like themselves. But to look like yourself is to acknowledge that you’re somehow a little outside yourself; that some steps must be taken to bring you closer to having what gets called “personal style.”

“Personal style” is both inherent to fashion and its kryptonite. Fashion requires you to constantly look “like” yourself and simultaneously aspire to look like someone else. And the personal in “personal style” is political, as in the 1960s feminist slogan, used by Carol Hanisch to title her 1970 essay, drawing from a banner at the 1968 Miss America protest she organized. That this personal/political mashup centered on social concepts of beauty, promoted as if they were a personal quality of particular individuals, is key.

Selfie by Sophie Fontanel, fashion writer, age activist, and Instagram star

Style is not identical with conventional ideas of beauty, though they have a close and uneasy relationship. The French fashion writer, age activist, and Instagram star, Sophie Fontanel, wrote that taking selfies for her account had both liberated her personal style and had made her feel comfortable, for the first time, with how she looked.

Looking at the political in the personal, fashion may work more like one of Foucault’s technologies of the self: social rituals for body and mind that become so habitual as to seem personal. Taken to a systematic extreme, as in army or school uniforms,these technologies’ constraints produce an “excess” of what they exclude. It’s those forbidden personal sartorial touches that afford us, as designers from Westwood to Galliano have known, (literal) pockets of resistance.

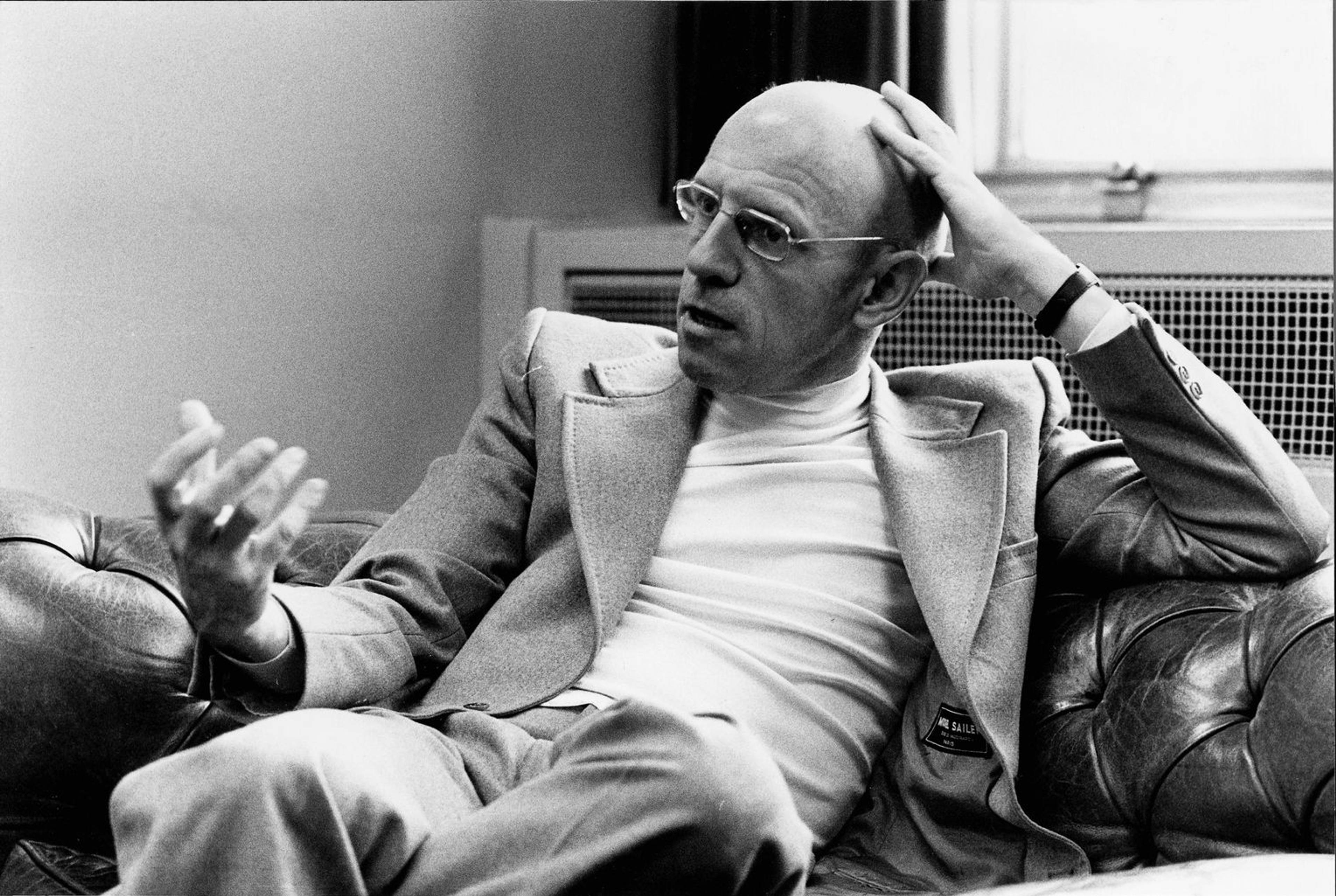

There’s an explicit take on this in Jean Genet’s super-homoerotic short, Un chant d’amour (A Song of Love, 1950 – currently available on Mubi), in which male prisoners, in various states of dress and undress, touch their own bodies through their clothes, as though they were touching each other through the walls that divide them. Their own clothes (not prison uniform) form a second skin: they are the self, but not quite. Foucault, famous for wearing variations on the same skintight turtleneck every day, a Bond-villain look that made him instantly recognizable, did not write about fashion.

Michel Foucault at a conversation in the SPIEGEL office in Paris, December 9, 1977. Photo: DER SPIEGEL

Still from Jean Genet, Un chant d’amour, 1950

The BOGOF (buy one, get one free) gift of style under capitalism is not only the opportunity, but the pressure, to find new selves. But there’s a melancholy to the expectations of “growth imperative,” to fashion as the pursuit of a particular kind of self that can only be constantly expanded.

To express your “self” with clothes is to turn away, to some extent, from fashion, to be “out of” fashion. This visual marker of a subject who’s not subject to the system is exemplified both by those seeking to show their opposition to it and those asserting their control over it. But, just as Foucault’s “excess” of resistance is squeezed out of the toothpaste tube of uniformity, what looks like countercultural personal choice is just as often deeply embedded in the systems it defines itself against. What’s more bourgeois than “boho”?

Chloé_FW24

An alternative move can be to choose a personal style that’s impersonal. But “wrong.” Steve Jobs’ identikit casual wasn’t what was expected of tech entrepreneurs back in the day; Slavoj Žižek’s stained T-shirt is normcore of a kind that’s unusual in academic circles. Fran Lebowitz’s personal style is impersonal – on a man. It’s just not expected on a woman.

So why not wear only what you like every day? I don’t mean what catches your attention. I mean only what looks most like you. Would that be rebellion? Should I limit myself to always feeling good, to never trying anything new? Narrowed down to what’s only “me,” I feel a lack of the feeling that I need to be completed, the Lacanian lack of a lack.

While acknowledging that fashion’s (over) production of the self must change, it would be wrong not to acknowledge that it’s one of the few areas of self-expression to offer the opportunity of becoming, even temporarily, someone else.

Sometimes, I want to outsource myself. This is why I love the impersonality of “ready-to-wear.” The twentieth-century liberation from working with the limits of your local dressmaker, or your own skills (as Anne Boyer did in her 2015 book Garments Against Women), has gone hand in hand with a lot of bad things: untraceable supply chains and labor alienation – meaning easier workforce exploitation, not to mention environmental destruction. While acknowledging that fashion’s (over) production of the self must change, it would be wrong not to acknowledge that it’s one of the few areas of self-expression to offer the opportunity of becoming, even temporarily, someone else.

To update Isabella’s statement, remaining only like yourself is key. This is self not as end goal but as pursuit. It’s not being yourself that’s important, but becoming. “Becoming” can mean “flattering,” but it can also be taken literally. Maybe it’s time to turn away from style – and self – as “personal” and think about them as situations, like the situation of my Vinted jacket, created by an interchange not with the aspects of the fashion system that want to sell me on novelty, but between my personal style and that of its former wearer. Not personal, but interpersonal, style.