Happy New Year. Fashion new year takes place, as everyone knows, in September. Shows are set in their inverse season: fall shows in spring and spring in fall. The big fashion seasons are, in any case, seasons of transition. In the fixed seasons of summer and winter, fashion hardly exists. Then there are the restless “cruise” or “resort” collections, the sub-season within each changing season. In a culture of monthly “drops,” each offering the identical chance of self-reinvention, fashion will seize on any hinge of change, and make the calendar New Year a kind of sub-new year in the fashion calendar.

Fashion doubles down on New Year’s illusion of perfectibility. Matchesfashion.com just emailed me their “2024 Style Resolutions,” most of which aimed at making style stand still (aka investment dressing), while simultaneously asking it to move on: the tautology of the “updated classic.” We want to be the same and we want to be different. We want to be our authentic selves so long as these are the selves we dream of being in the future. We don’t want to trash our wardrobes (all those “investment” pieces) while following Ezra Pound’s injunction to make it new. (Pound’s phrase itself wasn’t “new” but a story recycled from the works of neo-Confucian scholar Chu Hsi, about the first king of the Shang dynasty, proto-influencer Ch’eng T’ang, who was reported to have owned a washbasin decorated with this motivational slogan.)

It’s impossible to have the right jeans. Fashion dictates that by the time you are wearing them, they are exactly the opposite of the jeans that are in fashion, which exist only as prediction.

Jean shapes in particular change so frequently that, more than being a sign that the wearer is in fashion, they’re a sign of fashion itself, not only a barometer of how fashions change but revealing the structure of fashion as change. And also that it’s impossible to have the right jeans. Fashion dictates that by the time you are wearing them, they are exactly the opposite of the jeans that are in fashion, which exist only as prediction. Haruspices have Cassandra’d the return of the low waist for some time. 2024 is also apparently the year of the return of skinny jeans. It’s 2010 again, the cycle complete.

Last decade’s skinny jeans morphed until, by 2016, they were high-waisted and contained lycra, which drew them so many fans in the non-skinny population. “I finally gave myself permission to dress my body in a form-fitting item… My big legs felt luxurious underneath this fresh type of denim. I was almost, sort of, comfortable,” wrote fat-acceptance activist Marie Southard Ospina at Refinery29, mourning the demise of the style in 2021. I’ve seen predictions of the skinny jeans’ return as early as 2022. Does this really constitute a break? If the perfect storm of trends combines in 2024 denim, the new skinnies will also be low-waisted and lycra-free, as tough as any other unfulfillable New Year’s resolution.

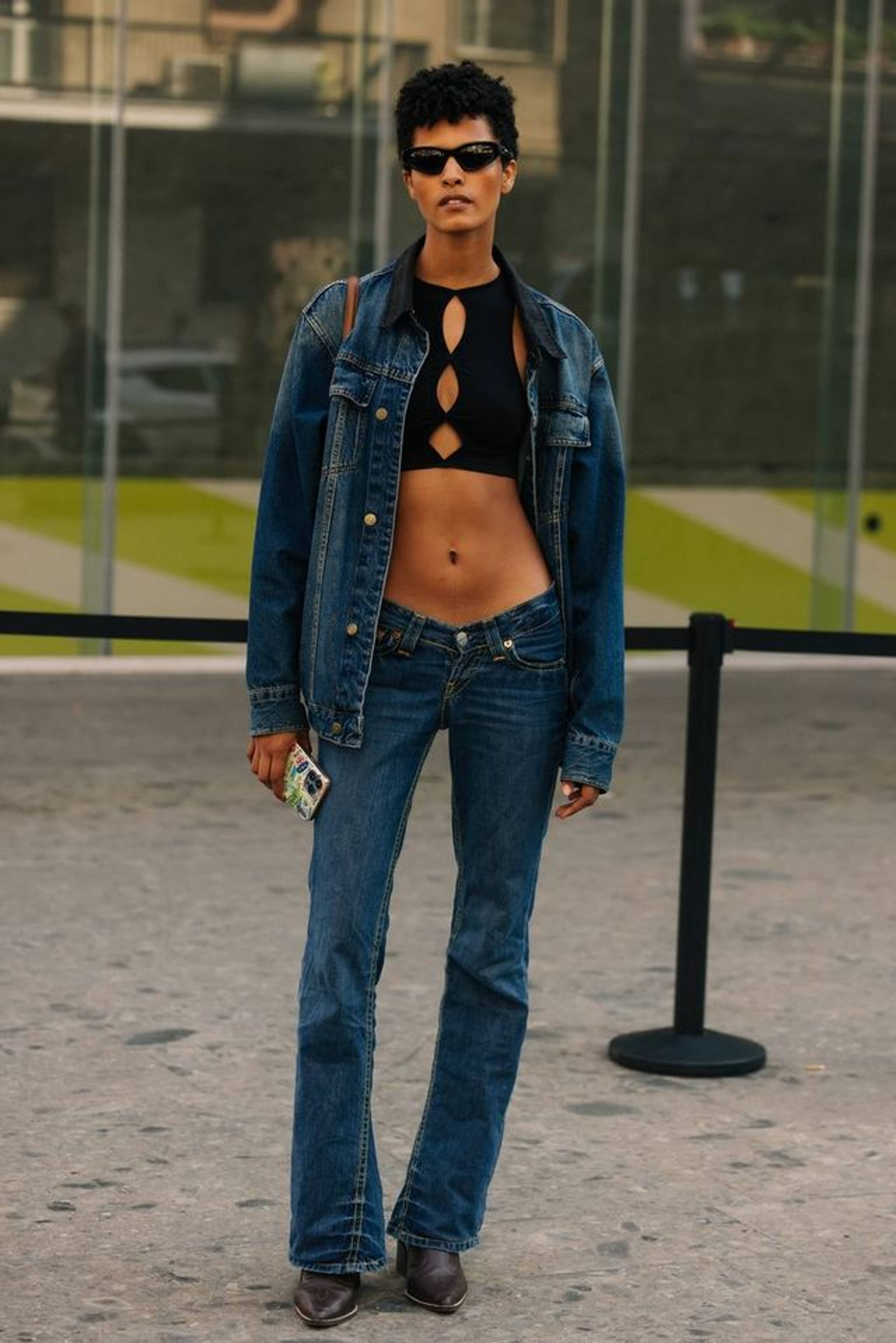

New skinny jeans “perfect storm,” Milan Fashion Week SS23 street style. Photo: Darrel Hunter

The “skinny” in skinny jeans is a transposition, a (literal) figure of speech. It’s not so much the jeans are skinny, but that’s the figure they require of the wearer or the figure they promise to deliver. In ancient Greek rhetoric, this is hypallage, also called a “transferred epithet,” in which the syntactic relationship between two terms is interchanged. With “skinny jeans,” this transposition is two-way, so it also counts as another rhetorical device, personification: the jeans, claiming a human attribute of skinniness, begin to have more agency than their wearer. Low-waisted skinny jeans are a plague of frogs, an unavoidable act of God. Fashion, as it’s so often figured, as “dictation.”

The new skinny jeans rumor is mostly put about as a negative, the opposite of the typical fashion speak gushing enthusiasm. Why fear fashion? Why feel it’s coming for you and there’s nowhere to hide? There are enough fashion columns telling you to “wear what you like,” as though this were easy to define, and as though liking were not at least partially social. Fashion necessarily encompasses these alternatives as part of what Michel Foucault called “discourse,” the hegemonic framework that sets the limits of epistemology while hiding its own power to do this by harking back to some mysterious a priori origin outside itself. In fashion, this is usually a quote by Diana Vreeland. Commentary or critique is allowed by the discourse: “it gives us the opportunity to say something other than the text itself, but on condition that it is the text itself which is uttered [re-iterated].” This repetition only seems to offer a new perspective: “The novelty lies no longer in what is said, but in its reappearance.”

In other words, the reappearance of a style of jeans means you can wear the old style only in the context of the new, and vice versa: the negative of a style always hovers around your look. Whenever you wear the new skinny jeans, you’re also wearing a ghost pair of baggies. I haven’t noticed skinny jeans on the street yet, except on people who are still wearing them from the last time around. Or maybe I can’t read a discourse so layered that, layered on the two conceptual jeans you already have on, there’s another pair of old-style skinnies you’re definitely not wearing. You can’t wear the “right” jeans for the wrong reason. That would be cringe.

So it’s bad to look good? Bad to achieve the New Year’s resolution you were working toward twelve months ago? Yes, because fashion is not an end point, it’s a process.

Cringe, far from making change impossible, is the hinge on which fashion turns. With denim, this may have started with “mom” jeans, then “dad” and “boyfriend,” all jeans whose various kinds of dowdiness or obvious “bad” fit became desirable, until only “fashionable” jeans were utterly unfashionable. Lean into the cringe and you’re getting somewhere. Amy Smilovic, the CEO of Tibi calls this the “good ick,” that hint of mental discomfort that offers something new. Smilovic usually brings it with such déclassé (because let’s not pretend that ick isn’t all about class) items as a white patent shoe, or a neon turquoise synthetic ruched top that looks like a disco swimming costume, changing up a classic wool blazer or a “too elegant” silk slip dress.

So it’s bad to look good? Bad to achieve the New Year’s resolution you were working toward twelve months ago? Yes, because fashion is not an end point, it’s a process. The French philosopher Jacques Rancière has a similar theory about art: anything considered “not art” is ripe for conversion, because art is “constituted and transformed by welcoming images, objects, and performances that seemed most opposed to the idea of fine art.” Transposed to fashion, the only constant prediction is unpredictability, which means that whatever you’re wearing right now is only in fashion if it’s the least fashionable thing you can think of.