After whatever you celebrate (or not) in December, now ’tis the season to be sorry. January is sold to us as the month of regret: of nausea for last month’s excesses of all kinds of consumption. Whether your month is wet or dry, January asks you, like Ezra Pound, to “make it new.” Toxic wellness haunts TikTok with the specter of the self you could become. Simultaneously, influencers – and de-influencers – tell us to downsize our closets, if only to make room for something new. Or rather, something old, as we’re dealt last season’s desires, cut-price, in the January sales.

Sales are a state of mind. Once part of the seasonal cycle, they now happen year-round. So, paying homage to the January discount period embeds a second layer of nostalgia, not only a for the recently “outdated,” but for a world of physical shopping which used to require an investment not only of money, but of time. Both the time spent getting to and shopping at a particular location, and the time spent waiting for the sales to begin.

Some brands make a point of never discounting: French luxury cashmere label Maison Alexandra Golovanoff had a series of “No Play Black Friday” Instagram posts in November. “We do never go on sale,” the designer answered a question on one of the posts. “We keep a small production, the best price point possible, the best quality possible, all year round.” With little difference between seasons or collections, and no discount periods, her range is, literally, “timeless.”

Under socialism, perhaps, we’ll know the price of everything because we’ll know the value of everything. There will be no buyers’ remorse, and there will be no January sales.

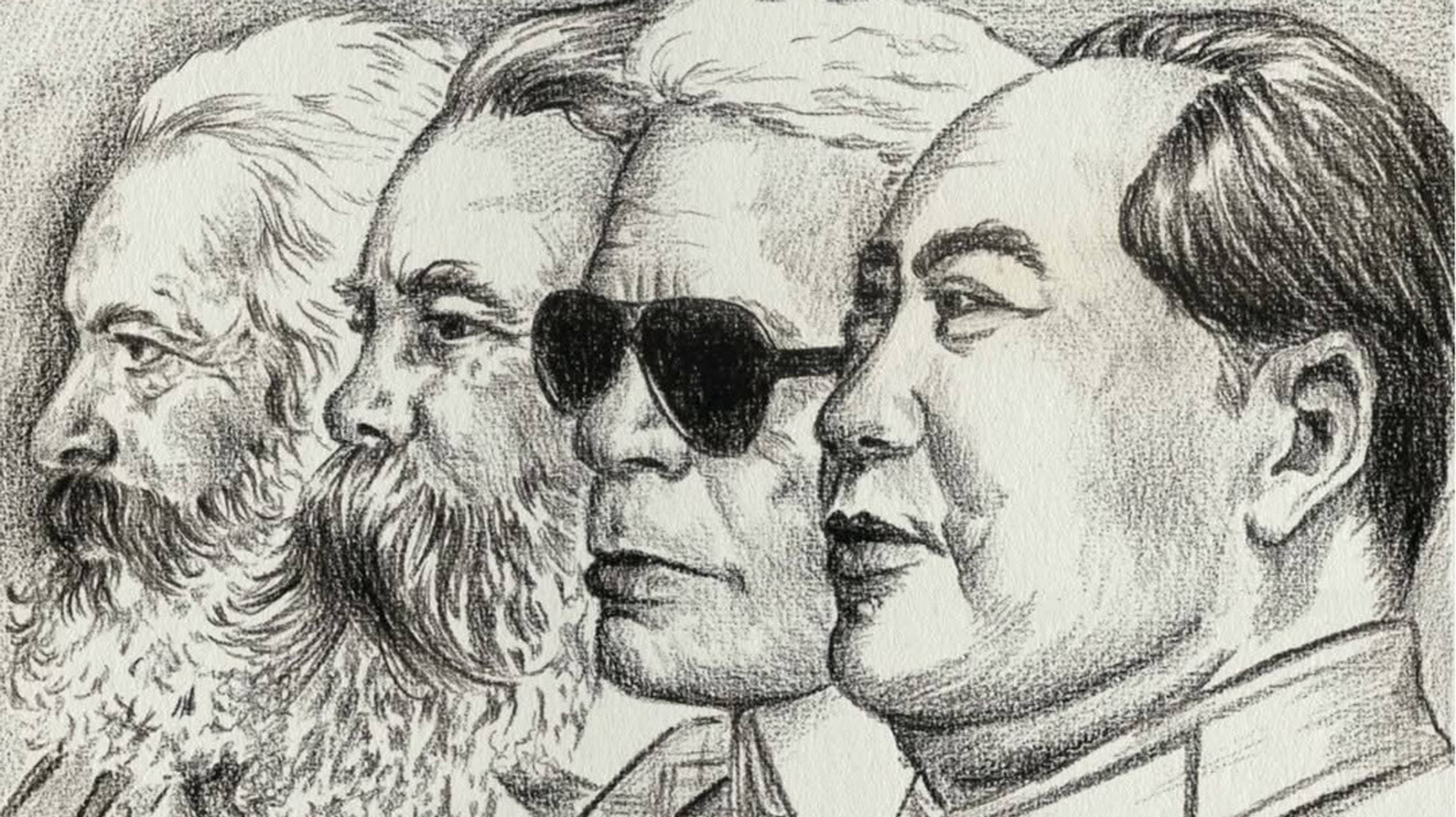

Jean Touitou, of A.P.C., a brand that has only recently begun to discount internationally outside the official sale periods that have legal force in the brand’s home country, France, has frequently spoken out about what he calls le système du cyber-mercantilisme (the cyber-mercantile system). In December, his Substack featured a dystopian end-of-year fashion fiction, The Perfect Storm, in which the gray market’s discounting of price-inflated designer goods online developed into incipient world war. As, who knows, it might. Developed in collaboration with the fashion editor Anne Boulay, the story features a recurring pencil illustration by Inès de Chefdebien, of a Mount Rushmore-like edifice featuring the faces of (I think) Marx, Engels, Mao and … Karl Lagerfeld.

Before he got into fashion, Touitou was a member of the Trotskyist Organisation Communiste Internationaliste. Under socialism, perhaps, we’ll know the price of everything because we’ll know the value of everything. There will be no buyers’ remorse, and there will be no January sales. But, stuck in this world, where the labor theory of value holds no sway, discount periods are one of the joys available, and remain relatively democratic. Though embedded in a commercial system that teaches us to yearn, as great a pleasure can be bought with a discount buy from Cos as from Prada. I’ve never equalled the delight of buying my first-pay-packet winter coat after stalking it for months till it went on sale. Perhaps uncoincidentally, it was A.P.C.. The delight, nearly as much as the coat was the discount. And, after months of waiting built-in, that delight was temporal.

Inès de Chefdebien, illustration for Jean Touitou’s fiction series The Perfect Storm

Sales are a matter of time. But, now that they happen so often, many online boutiques embed a “buyers’ remorse” period that helps retailers avoid returns. But they also know that, online in particular, where changing rooms are virtual, it can make sense to order a couple of colors or sizes, and return fashion “mistakes.” The culture of eternal returns became a big issue around 2018 and only increased during lockdown. Geoff Beattie, academic and on-screen psychologist for the UK franchise of Big Brother, commented that actually owning the garment is “the least exciting part of the process. If you’re a returner, you get all that excitement for nothing.”

Under capitalism, mistake is vital to our libidinal economy. The cycle of desire, disappointment, and regret is tied into capitalism because the rise of capitalism was tied to the rise of the idea of the individual as the engine of personal fulfillment. Because “our” mistakes seem personal, rather than predictable systemic outcomes of engagement with commercial systems, we feel bad. On-sale clothes already have regret woven in. Often the designs that failed to fly off the shelves, or that were returned, they are permeated with someone else’s sartorial disappointment. According to Rebound (a UK retail analysis company), in 2024, a third of online fashion buys were returned, while the British Fashion Council found that, in 2022, 75% of returns became landfill.

Fashion lives on surplus, because fashion is excess. Whether you buy it at Gucci or TK Maxx, ASOS or Vestiaire Collective, a fashion buy is in excess of everyday spending, its pleasure often put down to its différance from the quotidien. But a special kind of excess is created by mistake, and the margin of error seems crucial to fashion’s creativity. When fashion goes on sale, from army surplus and outlet shops to thrift stores and online resale sites, this has always facilitated moments of sartorial invention.

John Galliano, “Recicla” for Maison Margiela, FW2020/21

The critic Walter Percy, in 1958, defined “Metaphor as Mistake”: the most creative language requires a disjunct between an image and its referent, inviting some work by the reader to bring them together. Mistake is how some of the most inventive fashion works too, from broadbrush deliberate “mistakes” – the eternal “underwear-as-outerwear” – to the subtler joys of something made slightly “wrong,” like a “classic” blazer in recycled polyester. It’s possible for “just enough” surplus to be utilized at scale with little eventual waste, as in John Galliano’s 2020 Recicla collection for Margiela – one-of-a-kind pieces adapted from old garments. The seams on the outside, these pieces wore their unregretful mistakes on their sleeves.

I could say happy new year, but instead, I’ll make it many happy returns.

___