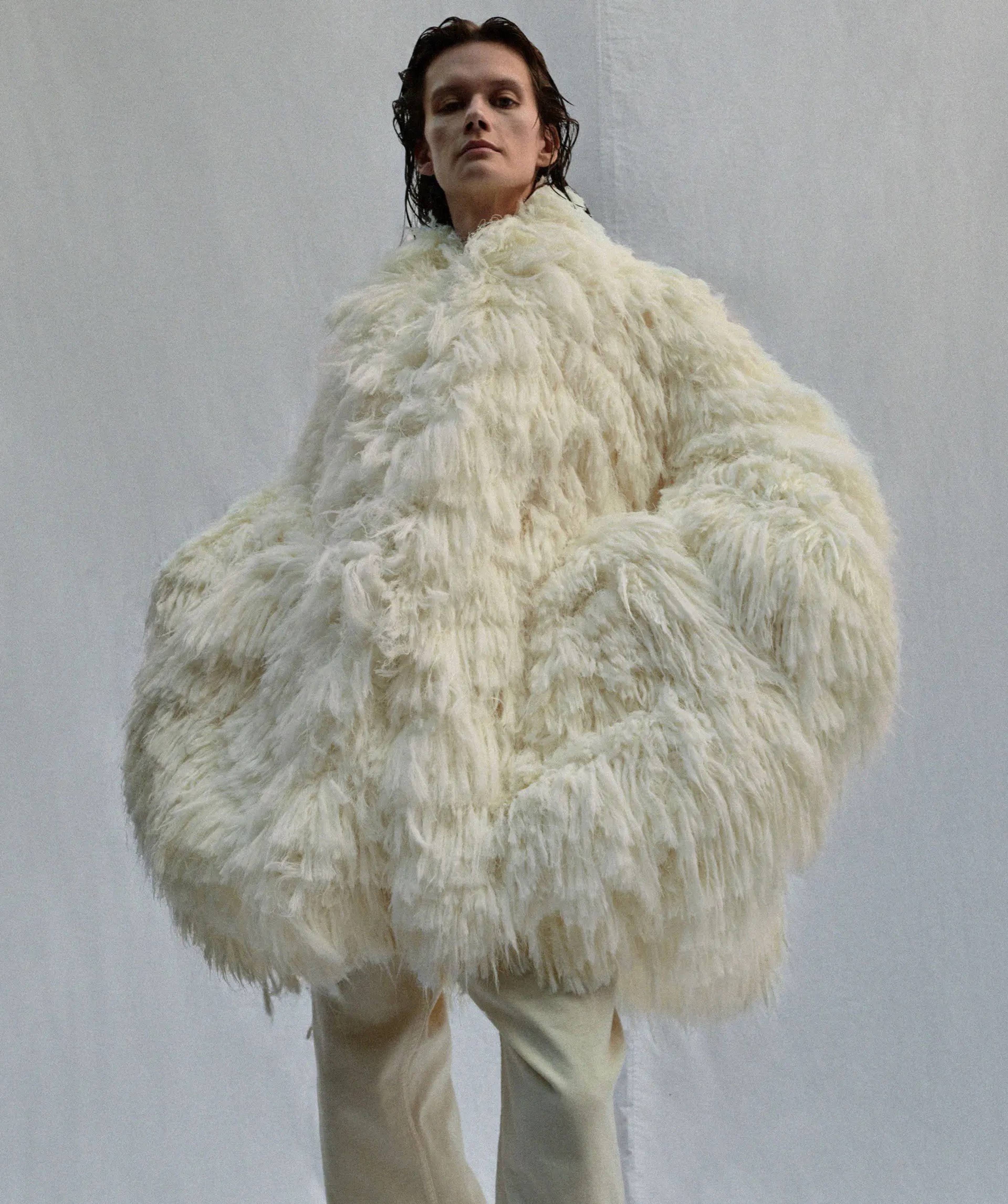

It’s fall and texture is – as it is, every fall – very big right now. I mean it’s literally big, like the “big bird” coat from Phoebe Philo’s long-awaited and astronomically expensive redux collection.

If “quiet luxury” has become 2023’s stealth trend (whether you blame Gwyneth Paltrow’s courtroom wardrobe or the popularity of the Succession HBO series, think normcore, but cashmere), Philo’s coat is so expensively reticent that it won’t even tell you its price (though the matching trousers, selling for 3,800 euro, might give you a clue). What are you buying when you buy this coat? For a start, you won’t be buying it because you can’t even afford to ask what it costs. But you’re probably buying into its story (including by reading this), and text adds texture to any garment. The Philo story was woven not out of the designer’s presence but her absence. The scarcity narrative Philo sparked when she left Celine in 2017 created a generation of Philophiles who gave “old Celine” mythic status. Her return with a high-priced textured collection at once in, and beyond, most of her fans’ grasp, only backs this up. As does the absence of a price tag on the coat. If money talks, silence speaks volume[s] here.

The coat has no price but it has a description. It’s a “Coat in cream glossy viscose twill with all-over hand-combed embroidery. The coat has elongated bell sleeves. Close-fitting at the top of half of the body, full from the waist down. Textured surface.” In queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s 1997 critical anthology Novel Gazing, Renu Bora proposed “texxture” as an interface for interchange, a space in which one object can affect another – in which people become things and objects touch back. These “surfaces” aren’t experienced by the senses but via writing, an invitation to feel (both physically and emotionally) via what I’d call “text objects” – adjective and adverb-laden passages that suggest a person or an object’s capacity to carry affect. This process creates an interface between the reader and writer for feelings that have often been kept in the literal closet. Bora claims these sensual descriptions as profoundly queer.

This says something about queerness as the performative use of language, not to describe objects directly but to synthesize text with texture to create a situation – a little like a fashion editorial with its vital descriptive captions, which Roland Barthes called the “vestimentary linguistics.” “It is not the object but the name that creates desire; it is not the dream but the meaning that sells,” he wrote in The Fashion System(1967).If desire is the hinge on the epistemological closet door that links the IRL texture to the text, Barthes aligns desire with capitalism: with what “sells.”

So much fashion takes place in silence, which surely says something. Models don’t talk as they walk down the runway; the higher-end the boutique, the plusher its hush.

This idea of paying for texxture comes up again in novelist Alison Lurie’s The Language of Clothes (1981), where she talked about garments as vocabulary: the more you own, the more you can say. Sure, when I buy a garment it’s often because I want to say a new thing, but if I wear all my clothes (or words) at once, my style – sartorial or written – can tend towards matchy-matchy completeness, or excess. Bora’s maximalism is not the only “style.” As in writing, great fashion can also be aphorism, haiku, bon mot. That we talk about “reading” a look hints that style is more written than spoken out loud.

So much fashion takes place in silence, which surely says something. Models don’t talk as they walk down the runway; the higher-end the boutique, the plusher its hush. But so much fashion magazine prose is as flouncy as Valentino couture. It’s clearly not meant for everyday.

What’s more, the words in the editorials are oddly detached from a traceable source, captions are not credited (Death of the Author, anyone?). Who’s speaking here – some Anna Wintour of the imaginary? What voice do you give those words? It can’t be the voice of the model, who is not describing but being described. But why is the person appearing never the person speaking and why is the speaker/writer hidden behind the scenes? The cliché was, anyway, that models were dumb as any mythological girl turned into a tree, a star, a stone.

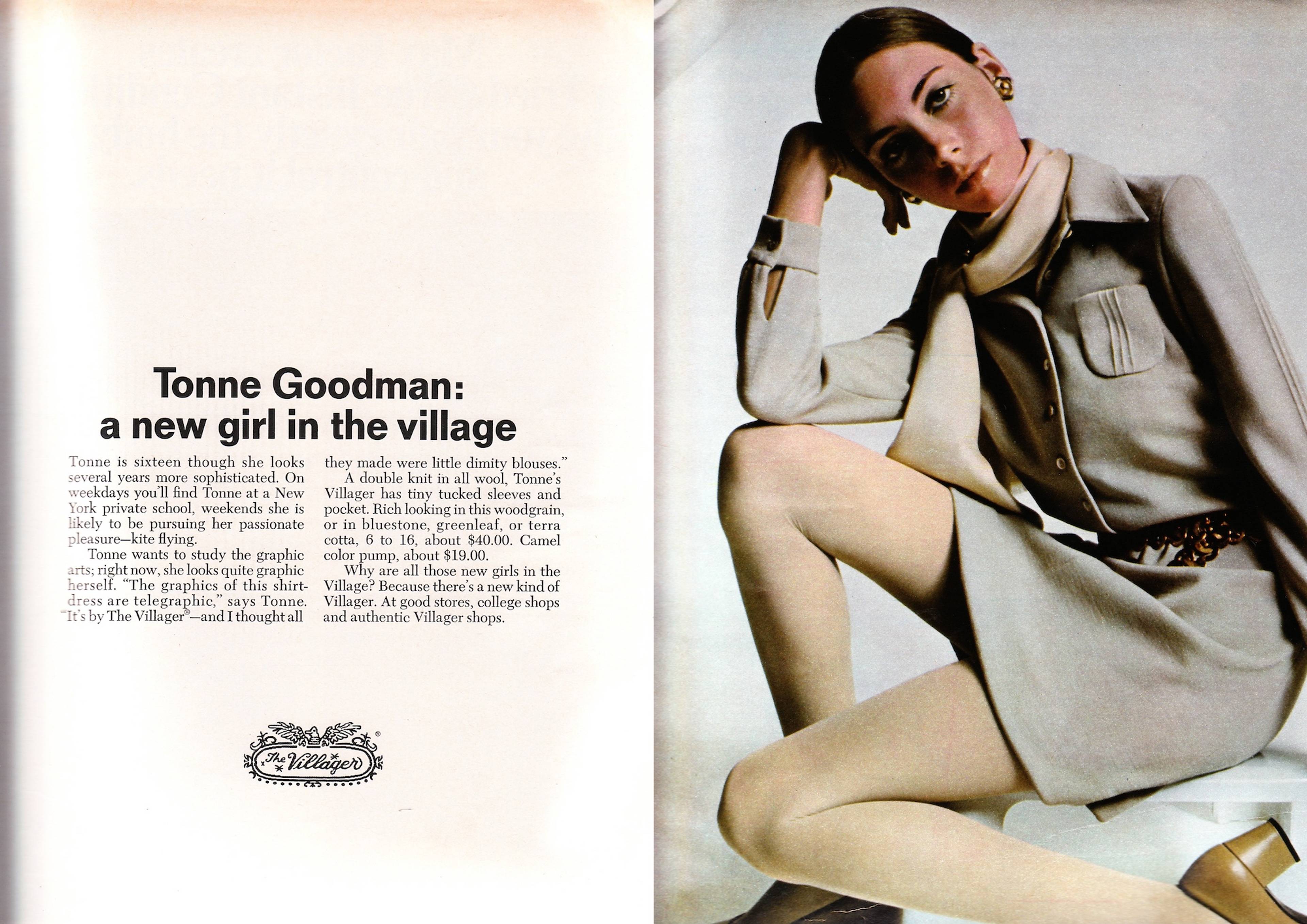

Still, some have occupied both sides of the interface. Tonne Goodman started as a model in New York in the 1960s and ended up as one of the Western world’s most powerful fashion editors. Goodman (a minimalist famous for limiting her fashion vocabulary to white Levi’s 501s) is pictured below as a sixteen-year-old in one of her first shoots. She can’t speak “directly” to the reader; she has to be described, her words reported. I don’t hear her voice here, but the writer’s words polish her surfaces which blend, monochromatically, with what she wears. The model, half person, half object, provides the queer interface between the clothes and the camera, and also between the reader and the page.

Tonne Goodman in The Villager campaign, 1969

The “language of clothes” is never the object it describes, but it is always also an object in its own right. Sometimes the shine of a glossy magazine reflects light off its own texxtural surface, reminding us that it’s not what it depicts, but that it has a materiality of its own. And there’s something ASMR about the way we encounter its material: the acrid smell of fresh print mixed with scent samples, the taffeta rustle of pages.

Take away the materiality of the magazine, and what place does the texxtural caption have in the age of digital reproduction? “The camera becomes smaller and smaller, ever readier to capture transitory and secret pictures which are able to shock the associative mechanism of the observer to a standstill. At this point the caption must step in, thereby creating a photography which literarizes the relationships of life and without which photographic construction would remain stuck in the approximate.” Walter Benjamin, in “A Short History of Photography” (1931), could have been talking about the playing-card-sized pics we take and see on our phones. Plus he just explained why TikTok (often silent as fashion itself) has subtitles.

Is there any sensual garment that isn’t woven with words? If textual texxture creates glossy surfaces, its invocation of the IRL weave or knit disrupts them. Barthes was wrong about “meaning.” Fashion is never only a statement: its “vestimentary linguistics” give us phenomenological feels. This isn’t only “meaning,” it might be muscle memory: a sensual reaction evoked by words that produces something beyond what sells, leaving the texxtural surface of the page or screen to stand in for desire itself. This desire is not directed toward meaning but its lack – to know what the Philo coat costs would kill any desire for it.