With all the time and thought (and money) I have spent on clothes, with all the rules, how can I keep on making mistakes? How can my outfit still sometimes miss the mark? How could I have thought that this look was (as fashion mags have it) “me.” Style is a gamble. It can only be felt along the bone. However many times you get it right, it’s still so easy to get it wrong. Then what do you do? Resell or give away – or wear it more until it “becomes” you – or you become it.

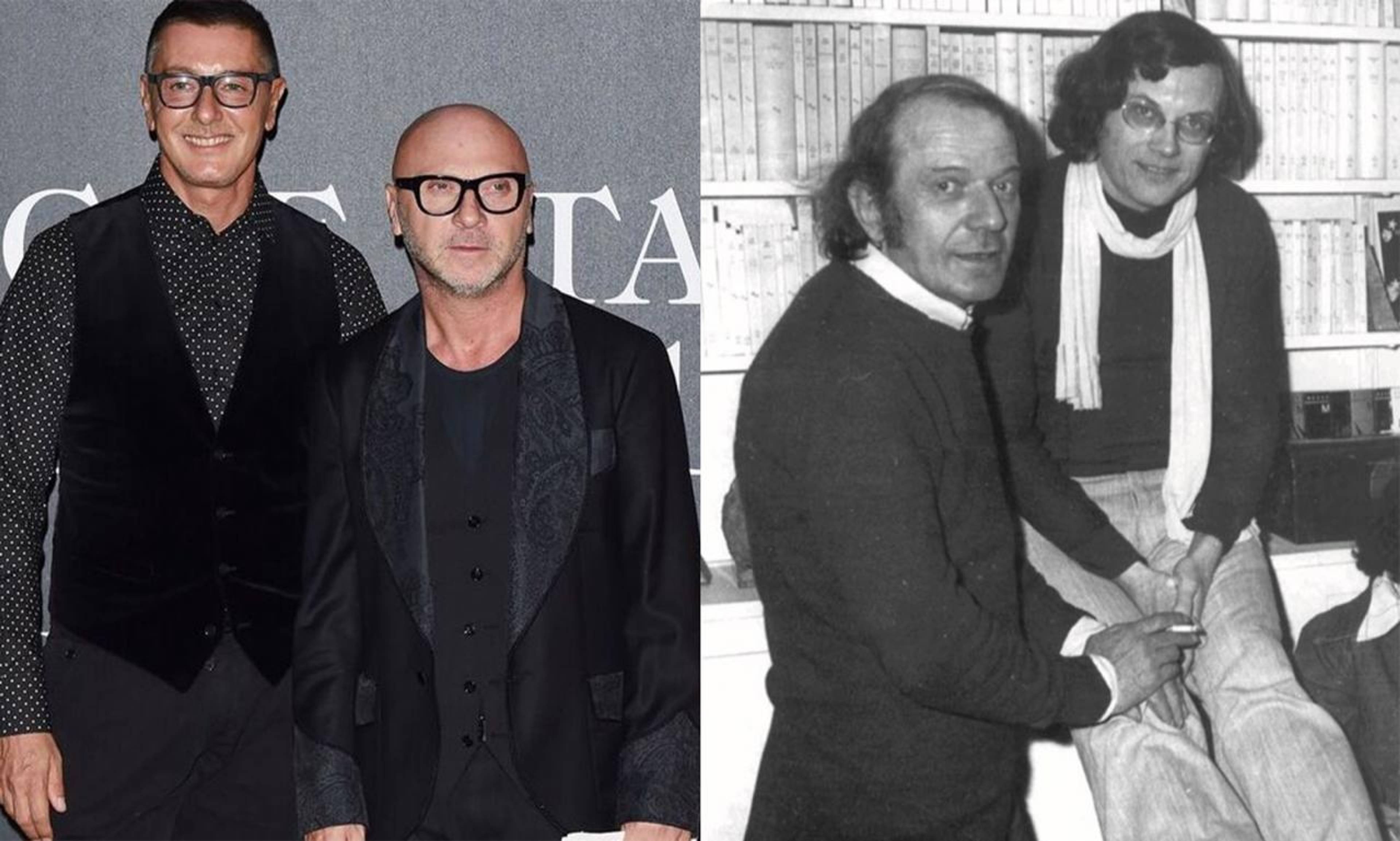

Becoming is a word they used to say when we now say “suit” – that three-piece of clothing that subsumes self. A “becoming” style relies on a more intimate exchange between body and garment. D&G (that’s Deleuze and Guattari, not Dolce & Gabbana) wrote that we’re “becoming” all the time. You can become woman or child or animal, they said, but you can’t become man. Though their definition works with an often misogynistic tradition of la donna è mobile, the idea that the “feminine” is less fixed isn’t a necessary sign of its inferiority to masculinity which stands, in D&G’s cosmology, for the molar, the intractably, inflexibly whole, unable to use a feather, a jewel, a brooch, to make a change.

Stefano Gabbana and Domenico Dolce. © Getty Images. Right: Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari

In 1772, the philosopher Denis Diderot bought a dressing gown. He changed into it and it changed him. A fancier garment than he’d ever owned, it didn’t even make him look good, but “stiff, and starchy, makes me look stodgy …. I now have the air of a rich good for nothing. No one knows who I am.” Diderot found that, changing, he had become someone else. Maybe D&G had it wrong, you can become man as in “the man,” the internalized superego boss externalized as a formal robe.

No one looks so much themselves as someone who’s worn the same coat every day for five years. If the goal is to look effortless, is style subtraction? I’m tempted by Kondo-slenderizing: could three multifunctional garments replace five? Could two replace three? Could I attain the magical goal of one that will do everything (yes, I’ve owned coats that become a jacket and skirt via a series of complicated zips)? Or should I buy “utilitarian” garment that give the air of hard-working virtue on all occasions. After all I like to dirty my clothes to fray them somewhat, to put my mark on them. Is this possession, or a fetishization of labor? Do they, like Diderot’s old gown “announce the littérateur, the writer, the man who works”?

Some minimal garments really are cheap and accessible, but visible simplicity often costs. The grander the designer, the less they “do” to a design. When Hedi Slimane took over from Phoebe Philo at Celine, one kind of minimalism replaced another. If Philo’s brand of minimal was futuristic (tech fabrics, modern shapes), Slimane’s fall collection in 2019 appealed to nostalgia. Old money, they say, wears old clothes, but the right old clothes. In order to be becoming, neither designer can stay entirely in the present. While Philo was modernist-utopian, Slimane is selling us clothes we already have, or the clothes we wish we could find in charity shops; vintage tweed blazers; distressed jeans clasped by a worn leather belt. Meanwhile, charity shops stock nothing but the ruins of other people’s jumbled polyester hopes. Ironically, Philo’s “modern” designs, now known as “old Celine,” are highly prized designer vintage.

Diderot, who didn’t object to the old clothes of a “peasant woman,” was disgusted by the appearance of the “courtesan,” whose aspirational rags were mismatched, torn and dirty. Hers are not the “right” kind of old clothes: “All is now discordant. No more coordination, no more unity, no more beauty.”

Why does Diderot punch down on the sex worker and not her richer clients? Could he be setting up an un becoming feminine stereotype – one that is the opposite of minimalism – that he could imagine himself “becoming”? Could we say, like Gustave Flaubert, speaking of the heroine he created as the locus of his consuming desires, Madame Bovary, c’est lui?

Emma Bovary, like Diderot’s courtesan, was always becoming, and that’s what made her unbecoming. Dressing beyond her means and social station, she was also neither one thing or another, and this showed, whereas the successful “show” of dress has such seamless “unity” that Diderot himself couldn’t achieve it. Both Diderot and Flaubert could imagine tasteless maximalism only as female. The images of women they created in text allowed them an outlet for mobile, non-molar becoming that couldn’t be figured out through the figure of a man.

Old Town’s unity suit “has the appearance of a primitive coverall but without the attendant problems of an all-in-one.” Right: Kosuke Tsumura’s Final Home multifunctional survival jacket, in production since 1994. Photo: @sickboyarchive

As for Diderot/Flaubert, clothes provide the hope that I can change, if I need to, if I want to, but they also underline the difficulty of this process. The changing room is a private place, and to be caught changing is anything from a joke to an embarrassment.

But not to change – to sit calmly in your clothes, thinking of neither the future nor the past – sounds like a wellness mantra. As an undergrad I really couldn’t afford clothes. This was before Vinted and Depop and eBay, before cheap fast fashion. It was even before internet shopping. In the 1990s you shopped where you lived, and if you couldn’t afford what you saw, you couldn’t buy. I couldn’t find jeans to suit me so I lived in two pairs of pants. The story in fashion guides of the time, as now, was buy less, buy good. But I couldn’t afford good. My pants came from the cheapest chain on the high street – New Look. They were both the same model: plain cotton, elasticated waist, one khaki, one black. In my very minimal wardrobe I have never felt so sartorially calm.

I sometimes want to be rewind to a situation where I buy nothing, do not desire. But how could I stay there, now that the temptation of the garment that will “unify” my look is always hanging in my wardrobe’s cognitive extension – on Vinted or Depop or eBay – diluting the currency of what I already have. The “convenient,” as Diderot wrote, “makes so many beautiful things and great evils.” The evils are not in the things themselves but in the action: the convenience of access.

The hardest items to get rid of are clothes you never bought, especially if they suddenly become available as vintage, forcing you to confront your original desire.

Shopping in end times, the one with the most clothes wins? If the essence of style is an action of judgement on the material, how can we continuously pick out without having too much? Imagining an outfit then wearing it is fast fashion’s modus operandi. But so much minimalism also depends on jettisoning everything and rebuying it “better.” So many designers pushing sustainability say, buy one thing but make it a piece by us. And many say this so often.

One in one out? The hardest items to get rid of are clothes you never bought, especially if they suddenly become available as vintage, forcing you to confront your original desire. To turn your back on that desire is to say goodbye to a version of yourself that never was. Hauntology: we are ghosted by future selves that never arrived. The problem is, the self is always changing and to catch it “right now” can be to see it at its most unbecoming, as when Sigmund Freud, glimpsing himself in a train bathroom mirror, thought at first that he was being approached by an unknown, “elderly man in a dressing gown.”

What style needs is an ethics of recognition, which is something that has to do with the self as it is neither in the past nor the future but right now, that brings together the dressing gown with its wearer. We need a redefinition of minimalism that embraces a minimalism of action rather than minimal appearance, which so often sneakily requires the act of buying more. Working this out requires working out what clothes do. Their primary utility (once we’re over the basics of keeping us warm/cool/dry) is meaning.

Diderot was the editor of the first French encyclopedia: the original capsule wardrobe of everything, stripped of materiality and slenderized into a unified volume of portable lexical meanings. We need a maximal minimalism that does not attempt unity of meaning, or of self. Learning from queer theory, this may involve not minimalist styles that attempt to pare meaning down to create a molar self, but pushing clothes’ meaning via camp strategies, to queer clothes, to mix their clashing meanings “tastelessly” like Diderot’s courtesan, until they unravel, perhaps literally as well as conceptually.

___