I finally sold the Isabel Marant biker jacket I’d bought myself for a fortieth birthday present. I’d had it long enough for its oversized cut to be in Vogue again. And it was saleable – in near perfect condition – because I’d hardly worn it. Why? Because when I wear it I don’t look like an off-duty model. I look like an IRL biker. As I packed it up for its new owner I thought about its ancestors: the moto I’d sacrificed living expenses for as a student – the cheap one I bought from a junk stall that fitted me to perfection but I nevertheless never wore – and I knew it would have no descendants. In letting go of the jacket I had let go of a dream, the dream of the universal, essential garment that looks good on everyone, appropriate for every occasion: what gets called a “classic.”

It’s the same dream that told me I could once wear dungarees without feeling I should be carrying a pitchfork, or a trench coat without looking like a cartoon detective. Why do I let these dreams go so sadly? What is a classic and why does it make me feel I’m missing out?

A classic is not a basic. Though they can overlap, a classic is something much trickier. A classic wears you, not the other way around. Many were literally uniforms and may have become classic because a large number of wearers had no sartorial choice. Choosing to wear a classic is a surprisingly high-stakes fashion gesture: you hand your values over to social structures bigger than you, histories of class, work, gender, race. But this gesture is not straightforward. If you can make a classic your own, engaging with those values, those histories, acknowledging or critiquing them, then you really have style.

“Consumption is not a passion for substances,” wrote Jean Baudrillard, “but a passion for the code.” In order to have code, something has to be decoded. And difference is necessary to interpretation. Or, in other words, a conceptual artist wearing a hi-vis vest is in a very different sartorial situation to a construction worker. There’s a labor that goes into interpretation for the viewer, but more for the wearer. The wearer is “working it.”

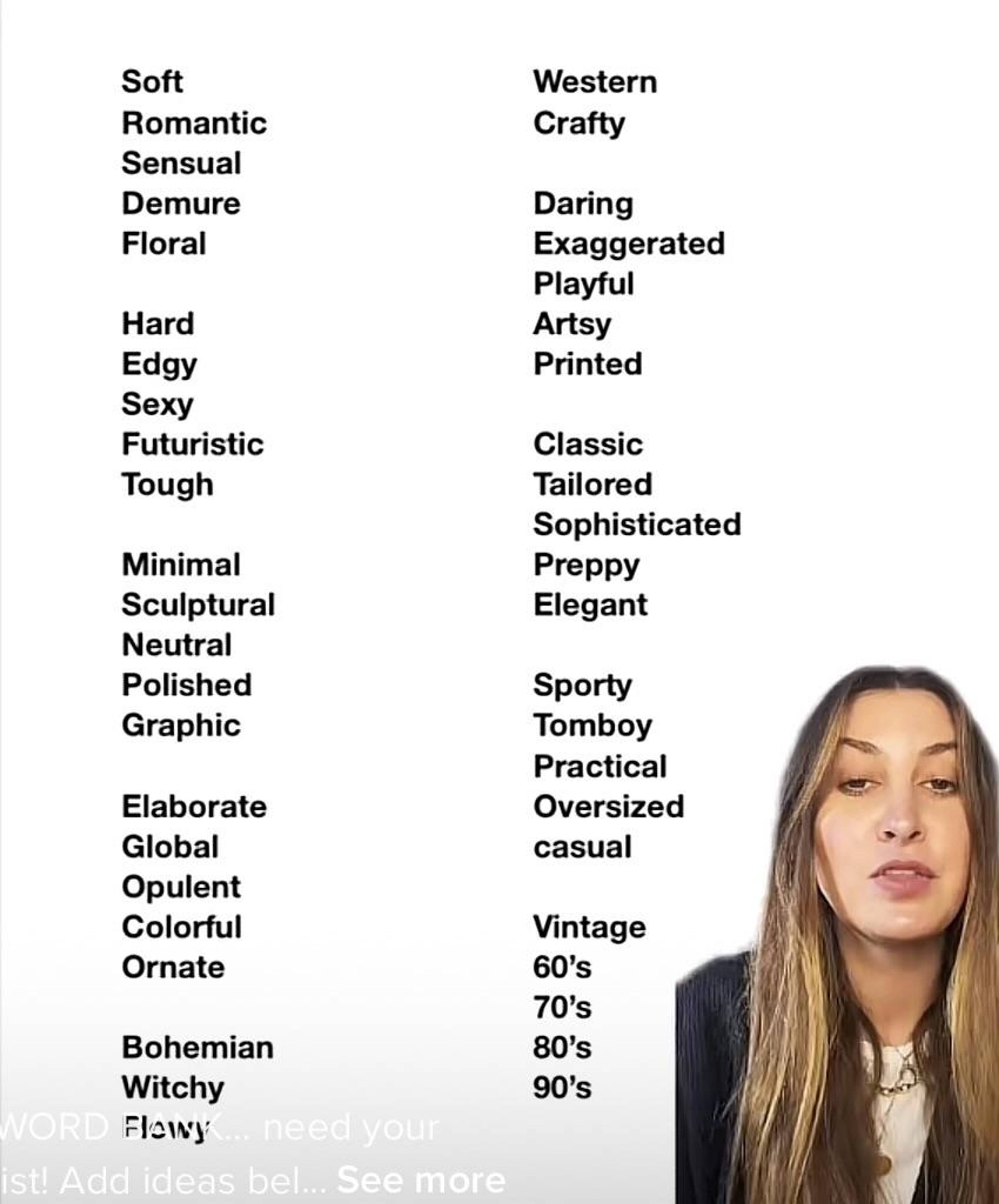

Allison Bornstein, “three word method”, TikTok

Miu Miu Ready to Wear F/W 2023

If comedy is tragedy plus time, then a classic garment is function plus obsolescence – it belongs to a profession or practice whose uniform retreated entirely into history or fiction.

This decoding gap is not only cultural but temporal. If, as a number of people have been said to have said, comedy is tragedy plus time, then a classic garment is function plus obsolescence. It belongs to a profession or practice whose uniform has changed, or which has retreated entirely into history or fiction. A classic signals literal and metaphorical redundancy. Are we mourning “authentic” jobs we never had? Contemporary sailors seldom wear square-collared blouses or farmers, smocks. But too small a temporal gap between the garment and its function and I might be mistaken for a contemporary professional.

Fashion is a matter of time, so a “timeless” garment demonstrates that you might be more in control, less subject to its vagaries. Wearing classics is a protest against time passing, ultimately against death. But, at the same time, a classic that is too classic is a deathly gesture: impersonal, frozen, lifeless. This could be the reason there are no real fashion classics. They are Platonic forms for which there are countless expressions, but no definitive instance. Even wearing the original is unsatisfactory: a lapel too narrow, or too wide, for current tastes; an oversized or undersized cut that runs contrary to the current vogue. Each provides a template that designers tweak each season to … make it something less classic, which will eventually pass into fashion history.

If comedy is tragedy plus time, then appropriating an entirely contemporary work garment is more like satire or social comment, which is why shell suits are still a more edgy “classic” than boiler suits. But, if you wear the real thing, you’ll find practical synthetics and lightweight plastic replacing canvas or chains, and a genuine overall cut for men can be uncomfortably loose on female-bodied waists and shoulders, and tight on the thighs. The idea is not to look like you actually work at that specific job, but that you’ve juiced it for its “adjectives” – a hot word now across the fashion internet.

Allison Bornstein, “three word method”, TikTok

What’s the deal with adjectives? They strip specificity and materiality from garments, leaving you with the essence, the feel, the code as advised by everyone from stylist Allison Bornstein’s TikTok “three word method” to Tibi founder and creative director Amy Smilovic’s weekly Instagram “Style Class.” But adjectives are as slippery as classic garments: could you sartorially convey Smilovic’s adjective “chill” without referencing a specific moment in material history? Creating new classics is a continual process of decoding and recoding: it’s all about drawing what’s “unfashionable” into fashion territory. As French philosopher Jacques Rancière wrote of art, fashion “is constituted and transformed by welcoming images, objects and performances that seemed most opposed.” Wearing a classic, the most reliable of garments, was always once the most radical gesture. No restaurant today would try to bar socialite Nan Kempner for wearing a 1966 Yves Saint Laurent tuxedo (spoiler: she took off the pants and was allowed to enter wearing the long jacket as a dress). Classics are most effective at the moment this recoding is enacted, as when hoodies crossed from sports-slash-lounge-slash-gangstawear to headline at Miu Miu this season, retaining enough of an edge to refer to their former functions.

Miu Miu Ready to Wear F/W 2023

And that’s my problem. When a classic doesn’t work for me it’s because, however much I mix it up, I feel subsumed by the garment’s former meanings. Could I possibly wear a peacoat or riding boots without looking like I’ve come straight from the foc’sle or the stables? Maybe a classic is only convincing when the wearer agrees to work with the garment’s original code, or has a clear idea of how to work against them.

About my jacket, the buyer defaulted. I could have put it back up on sale but I didn’t. Photographing it, writing about it, I’d fallen in love with it all over again. Or with the dream it was sold with. I tried it on. It was beautiful. It felt good. It still made me look like … something else. I put it back in my wardrobe to torment me for another decade, until I can work it. Or until it works on me.

___