The first time it happened I was eleven, and she wasn’t anyone IRL, just a photo. I’m not even sure she was “she,” or even “he.” They might have been “they,” not in the gender-neutral sense, but in the sense of a swarm.

What were they? They wore corduroy and wool that I could feel on my body, though I wanted to feel it via their body, which was still all rangy limbs that I’d recently dysphorically pubertized out of. I could feel the texture of the bark, the smell of autumn leaves on the trees they climbed. I didn’t only want to look like them, I wanted to be them.

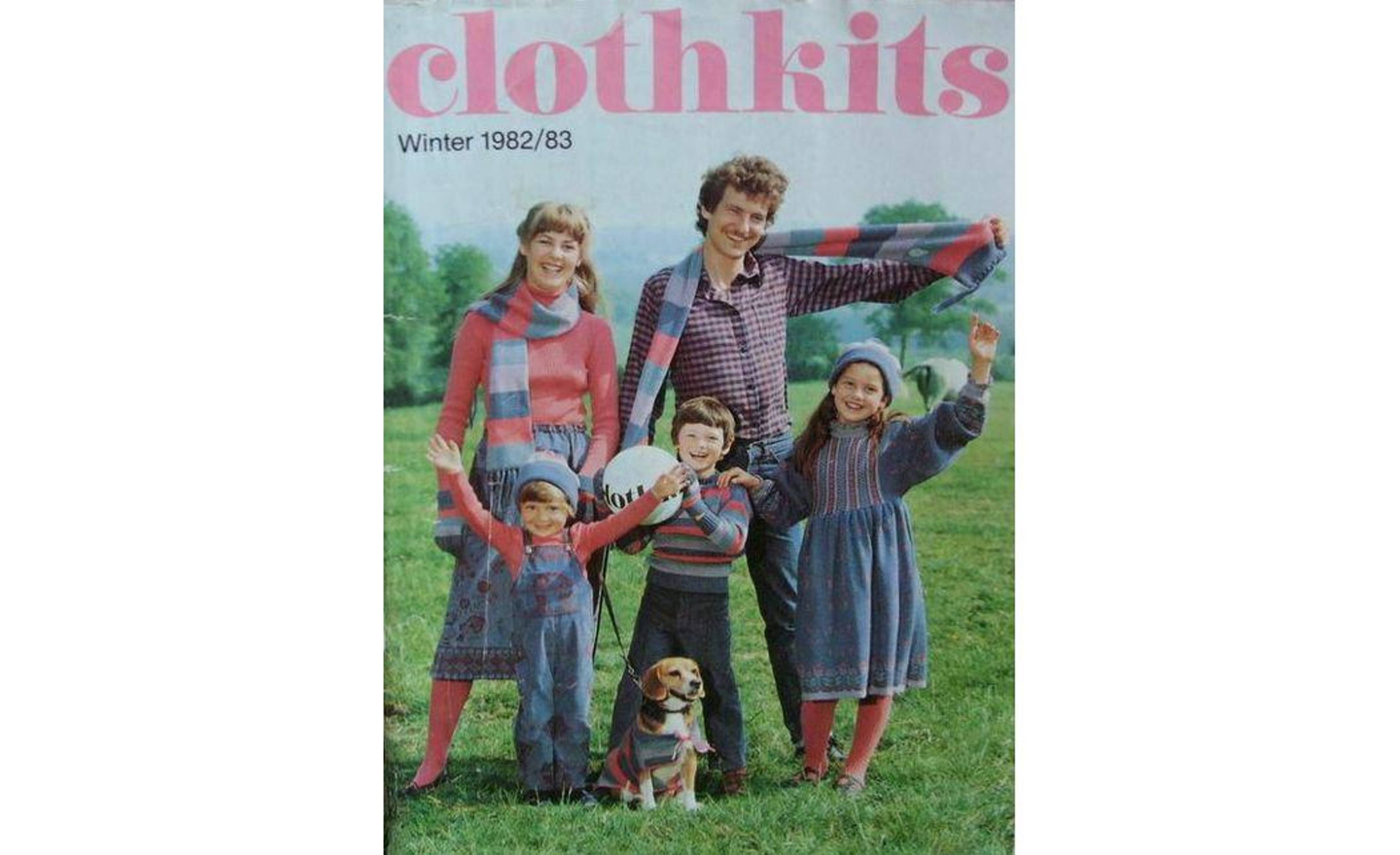

They were kids in the Clothkits catalogue. Not my copy but a friend’s. I saw it at her house where I could not only keenly feel the texture of their clothes but their lifestyle. They were so wholesome, in that they seemed whole and I seemed incomplete. Not that Clothkits clothes were sent out whole, but as fabric with pre-marked cutting lines, implying a whole other wholesome entry requirement – home-sewing skills, time to make your own clothes, a close-knit mother-daughter bond. The Clothkits kids’ clothes had a literal family resemblance to their designs for adults. In toning colors and artsy, folk-inspired prints found nowhere else, the clothes matched themselves. Self-similar, I liked them because they were “like.”

The gesture of liking is now inescapable. It’s the button we hit when we mean “want,” but also “agree” and “lol” and a whole range of other things. Whatever, a gesture of “liking” is always an acknowledgement of distance: we use it to mark something we do not have. Liking is an expression of lack.

Photo: Clothkits catalogue, Winter 1982–83

Wanting to be “like,” writes the critic Sianne Ngai, is key to “envy.” While this might be an “Ugly Feeling” (the title of Ngai’s 2005 book), it can also be a politically productive one. Ngai calls for envy’s redefinition from a passive and personal fault to a “motivated affective stance.” She shifts the emphasis from a lack in the envier, to a real quality in what is envied, which allows a “polemical engagement with the world.” My envy of the Clothkits kids let me ask why they had things I didn’t, and to define some of those things.

Ngai cites Barbet Schroeder’s 1992 movie, Single White Female in which stalker Hedra does not just envy the lifestyle of her landlord/flatmate, Ally, she seems to want to be her. The first thing she does is dress like her.

Bridget Fonda and Jennifer Jason Leigh in Single White Female (1992)

For GenX, the movie’s target audience, “looking like” seems particularly sinister. Brought up on a definition of authenticity as individuality expressed via aesthetic difference, why would anyone admit to wanting to look “like” anyone but themselves? GenX can flounder in the GenZ fashion world: why would you match your bag to your shoes? What gives with “knitted co-ords”? For the TikTok generation, identity is not signaled via difference. If your top matches your skirt, it doesn’t mean you “look like” your gran. In any case – as style is no longer defined as reactively generational – your gran is your (probably “coastal”) fashion icon.

As for me, I’m still subject to the false consciousness that how I look is somehow who I am. But I don’t always want to look like myself. I have no idea how I ended up this way. Some style decisions are a mix of conscious and contingent: I’d feel “fake” dying my grey hair, so I buzz it. I don’t love it, but it’s not a question of look. If I can’t “look like” I’d like to look, its because it’s just “not me.”

If the problem of style is the problem of self, it’s also the problem of community, sometimes tied only by a belt or a scarf or a photo of them on Instagram or the pages of Vogue . Personal style, like personal pizza, foregrounds the notion that both are made to share. A personal pizza may satisfy but sooner or later you run out of self. A single serving is never enough.

How do you find your community: these people who look “like” you? It’s no longer the people who live in your street, and this is something style can reveal. Take the case of the Amazon coat. In the winter of 2018–19, a basic-looking, sub-high-street priced down-filled parka went viral. No one knows why, only that one person copied another, until the coat became a thing, and the thing about it was people knew it had gone viral. Then it went more viral because people knew it already had. Then it got too viral and (like everything that looks too like) faced a backlash: no one had ever really liked it . Or no one anyone “really” knew.

Photo: Amazon coats, Instagram grid

Looking indistinguishably like someone else conjures a whole range of affects – it’s a joke or a celebration or a cause of uncanny unease. Gucci’s Spring 2023 show saw sixty-eight pairs of twin models walk the runway in matching outfits, holding hands. Like the handholding, identical dressing signals incompletely developed personalities, which can be cute or (as in Allie/Hedra’s case) sinister. There was something childish, or maybe childlike about the clothes too: oversized cuts, shoulders that overreached the models’ frames, clashing brights and big details, as though drawn with thick felt tip.

I can’t help but wonder if this is somehow linked to the TikTok trend that sees the same model show the same outfit styled differently, or more often as style-fail versus style-success. Playing with dialectics and creating a vocabulary of gestures, most often they balance how-to not with how-else, but with how-not; the “but” to Gucci’s “and.”

TikTok style is less about being different, than briefly and serially “like,” as in like a celebrity, an influencer, or a briefly-codified identity. Enabled by the quick (and cheap) changes made possible via fast fashion and Depop, what looks superficially, well, superficial, is a sophisticated attitude that blithely assumes a non-monadic, relational self.

There is no more collaborative art than fashion, nothing relies more on the immediate gaze of the other, and on modulation in response.

The consciously artificial nature of TikTok’s serially viral style identities places the dresser in a playful, posthumanist universe where Object-Oriented-Ontology rules. What’s so interesting about this summer’s TikTok-driven tomatocore trend is that it’s not so about looking like that girl who spends the summer in a tomato-infested region (basically Italy), but that the vibe can be got by putting literal depictions of the objects associated with what you’re not experiencing onto your body – as charms, totems, sympathetic magic. The aesthetic harks back to the hungry post WWII period when aspirational banquets featured regularly in fabric designs.

Back to Ngai’s take on Single White Female : turns out Hedra’s lack was prompted by the death of her twin. She doesn’t want to replace Allie, but to establish what Ngai calls a “non-singular” state that has potential as a template for feminist identities, able to overwrite the definition of femininity as necessarily envious. That this process is played out via “looking like” proves style’s radical capacity to propose states that are never quite “singular,” both as in “never-totally-unexpected,” as well as “never the product of a single intelligence.”

There is no more collaborative art than fashion, nothing relies more on the immediate gaze of the other, and on modulation in response. And it happens sometimes, this moment of recognition, of the possibility of community in which “being like” no longer relies on “looking like.” In a bar in Madrid, everyone drunk on sherry, a queer bearded stranger shrieks that they love my look. I shriek back. We have, within minutes, invited each other to numerous nights out. We never see each other again. They are wearing a silk flowered dress. Their nail varnish is eau-de-nil. They look perfect. I’m wearing a light tweed jacket and massive bleach-wash jeans, shaved head. Our nonidentical looks are an acknowledgement of a communal non-singular ethos. We may not “look like” but we “like.”

___