Summer’s here and that means I’m taking up more space than usual, or feel I am. The notion of a holiday requires me to appear, not as a different person but a different body. To be “beach-body ready” is not to be on the beach: it fetishizes the period of “readying.” This commercialized “femininity” is the performance of controlling “unfeminine” excesses and lacks: influencers spend me-time working on themselves at the gym, the hairdresser, shopping for outfits. If the late 20th-century celebrated the divide between work and “holiday,” created by a combination of travel-technology and the welfare state, now leisure becomes hard work, and this feminized work cycles round to become the leisure activity of those who work to be able to afford to do it.

For years, I often bought clothes that, by current standards, seem slightly too small. I didn’t think they were too small, I thought they were clothes I should “work at” fitting into, taking their tightness as a strict embrace. Not fitting was a fault, not in the clothes, but in me. Blame it on how the cult of size 0 played out in my generation; blame it on the weirdness of manufacturers’ unsteady size-inflation, which means I almost as often mistakenly bought too big; blame it on the low-cut skinny jeans that dominated the 2000s and much of the 2010s. Was this body dysmorphia or just the dysmorphia of late capitalism? Whatever, I literally didn’t allow myself to take up space.

If capitalism is the disease, fashion is the symptom. Fashion is too often a stage where patriarchy x capitalism is played out but is also a place where it can be worked on. On the catwalk, big clothes for women are back, bigtime, and have been for some time: huge pants, knee-length sweatshirts, The Row and Raey’s David Byrne suits.

Left: David Byrne’s Stop Making Sense Big Suit Tour (1984); right: Raey’s “giant” suit (current season)

What do these big clothes “mean”? Do they make the wearer look bigger, or smaller, more “masc” or “fem”? Which is desirable, and which is liberating?

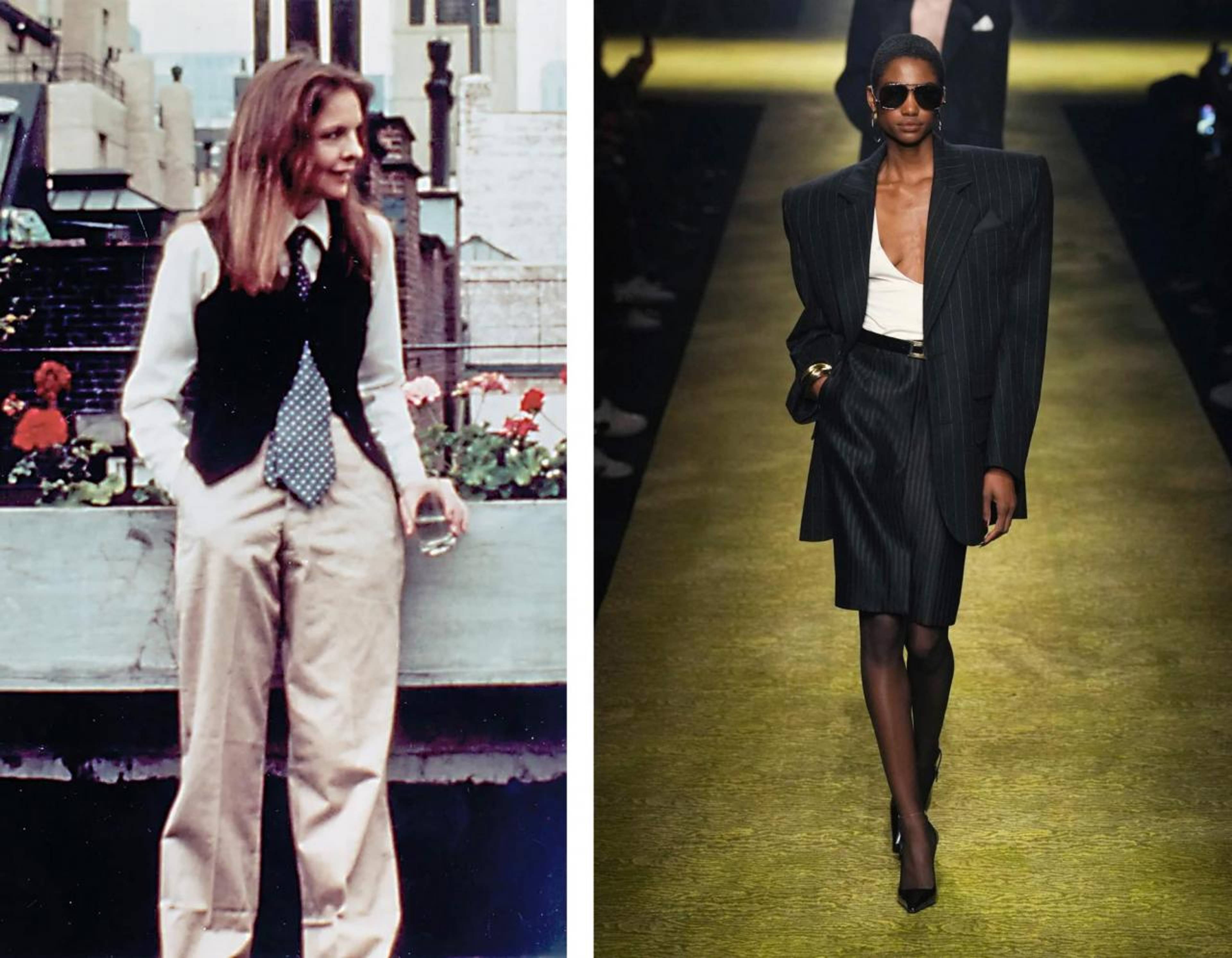

Bigness, like “androgyny,” is often skewed masculine. Oversized women’s clothes are frequently styles that have traditionally been coded male: blazers, trousers, suits. Is this appropriation of, or submission to, patriarchy? In The Language of Clothes (1981), Alison Lurie questioned the contemporary Annie Hall-inspired vogue for oversized menswear. Though a liberation from the uncomfortably constricting “feminine” clothes of the 1950s and 60s, she found the oversize look made wearers look “cute” and unthreatening.

But there’s more than one way to do oversize. There’s nothing “unthreatening” about YSL’s fall 2023 collection. This is partly down to Anthony Vaccarello’s use of aggressive business black with shades, but also, notice that the only oversized element here is the shoulders: everything else fits as standard. This takes the collection into exciting experimental territory but ensures more conservative buyers can look safe for work, minus the blazer, and still participate in the collection’s edgy buzz.

The woman who takes up space is both worshipped and ridiculed. The meringue- or maternity-dress-wearing monstrous feminine. So much fashion is a negotiation of this powerful archetype.

If the late 20th century holiday made leisure into labor, contemporary big clothes seem to be all about a kind of office work that’s increasingly eroded in our work-from-home gig economy. Is this a “back to the office” desire to reaffirm boundaries between work and leisure that have been lost? Vaccarello, in particular, references the sharp-shouldered Working Girl 1980s: nostalgia for the cubicle. Both YSL and Raey are selling office clothes – whether your office is the stockbroker’s or the art gallery – which gives them a different vibe to Annie Hall’s leisured “gentleman” look (interestingly Diane Keaton wore clothes from the men’s collections of Margaret Howell and Ralph Lauren, rather than old school menswear brands, unfiltered by retro fantasy).

If big is all about gender, and work, big is also a feminist issue.

Left: Diane Keaton in Annie Hall (1977); rightL YSL, FW 23

The thing is, women are so often bigger than men. The myth is that they are always smaller. “Boyfriend” jeans (my favorite cut is “distressed, pale boyfriend”) are designed to fit in a way that assumes your thought-experiment guy is bigger than you are, producing (if he’s not) a kind of cognitive dissonance, as well as a ghost guy she told you not to worry about , able to haunt any IRL hetero relationship. (As for “girlfriend” jeans: Is that “girlfriend” in the sexual or the platonic sense? And how does the borrowed “borrowed from the boys” myth, whose effect assumes a size difference, play out here?)

There are exceptional – and exceptionally gendered – occasions when women have traditionally not only been allowed but encouraged to be big: the bride, her wedding dress making her twice the size of her groom or anyone else on the wedding photos, foreshadows the pregnant woman. In the old days, it was assumed childbirth would swiftly (though not too swiftly) follow her (literally) big day. In both cases the woman who takes up space is both worshipped and ridiculed. The meringue- or maternity-dress-wearing monstrous feminine. So much fashion is a negotiation of this powerful archetype.

Maybe that’s one reason Cecile Bahnsen makes big girls’ clothes. And they’re “girl’s” clothes rather than “women’s,” exaggerated enough to point up the difference between them and any grown-ass woman wearing them, playfully providing a sophisticated inverse to the Annie Hall “cute” effect. When Bahnsen took a bow at her Fall 2023 show, she was dressed as (another horror film trope) an oversized doll, but everyone could see the dark pants and trainers under her skirt: street meets Princess Barbie.

Bahnsen has occasionally used bigger models to show her big clothes but most at this show were catwalk-standard thin. Showing his Valentino Haute Couture collection in January 2022, Pierpaolo Piccioli used a wider range of models, in terms of age, race and body, than has perhaps ever been seen on the catwalk. Haute couture (for the very few who can afford it) means big dresses for big occasions. The ultimate in conspicuous leisure, it’s possible that the patriarcho-capitalist demand that women work on themselves is most easily loosened for those who already have it all. Still, here were big women in big dresses worn neither over- nor undersized. Their clothes “fitted” them: it felt like a moment.

Left: Cecilie Bahnsen, AW23; right: Valentino Haute Couture, SS22

I still find it difficult to judge my own size. And to remind myself it shouldn’t matter. Size inflation has put shopping into freefall, which is, counterintuitively, no bad thing. When I can’t trust the size on the label, I have to go for what fits; not only in the conventional sense, but the sort of fit I’d like.

What I’ve learned from wearing big clothes is to hold my body differently to accommodate their volume. I don’t know if I’m morally “better” or worse for it, whether I look more vulnerable, or less, but both my clothes and I are taking up more space.

___