On a walkthrough days before the opening of “The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure,” curator Ekow Eshun rehearses his provocative premise for the show: that from about the 18th century, Black people have been depicted in artwork made by White European artists who have always looked at the figure. Leaning on Susan H. Libby and Adrienne L. Childs’s The Black Figure in the European Imaginary (2017), his catalogue introduction further explains: “They were ‘slaves and servants, historical figures, artists’ models, decorative motifs’ but rarely ever individuals credited with a complex interior life.” Eshun’s gathering of sixty-eight works invites viewers to hold hands with their twenty-eight Black artists and look with them at subjects who, in other contexts, are not treated with such kind attention – even if scanning and surveying artistic representations of human beings, and perhaps of Black people especially, always turns out to be more complicated.

To begin with, that I am looking with does not necessarily mean that the painted figure welcomes my gaze (or even that of the artist). I see a range of responses to the artist’s scrutiny in the Amy Sherald works that open the show. The young woman subject of A certain kind of happiness (2022) looks back at me pensively, like she is unused to being the center of attention. Conversely, She was learning to love moments, to love moments for themselves (2017) features a subject whose akimbo hips confront the viewer confidently, as if to say, “I see you, watching me. What’s good?” A third painting, Sometimes the king is a woman (2019), features a woman who assays us with a little aloofness, as if unsure of our intentions. Sherald has given me intimate access to the apprehensions of subjects who, seemingly candid, do not perform the kind of blackness expected by audiences – and they also don’t necessarily accept my offer of allyship.

Kimathi Donkor, Harriet Tubman en route to Canada, 2012, oil on canvas, 210 x 165 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Niru Ratnam, London. Photo: Tim Bowitch

Michael Armitage, Kampala Suburb, 2014, oil on Lubugo bark cloth. 196 x 150 cm. Courtesy: the artist and David Zwirner

In Kerry James Marshall’s Nude (Spotlight) (2009), a naked female figure

lies in bed, a crumpled blanket pulled down to her pubic bone. Lit from above by a large, white beam, her gaze turns toward the artist while her hands cradle her head between two pillows, depicted like I might look at a lover. This is one of the hidden beauties of this exhibition – that, as viewers, we get to participate in this intimacy without reducing the characters to emblems of sexual exploitation or ourselves to voyeurs. Mainstream US popular culture does enough of that. Elsewhere, Michael Armitage’s Kampala Suburb (2014) shows two men kissing. However, the figures are rendered in vague terms, in silhouettes offering few clues as to their context, as if the romantic gesture were illicit – a secret liaison I am allowed to witness because I am looking with.

Moving through the exhibition, the looking at times turns toward speculative

fiction. In Harriet Tubman en route to Canada (2012), Kimathi Donkor imagines the abolitionist gun in hand, both threatening and entreating a White man to find the way north to freedom. Lubaina Himid’s The Captain and The Mate (2017–18) constructs a more recuperative narrative from the fate of the French slave ship Le Rôdeur (The Prowler), whose captain ordered in 1819 that thirty-six Africans blinded by sickness be thrown overboard, deemed more valuable as lost cargo. In Himid’s retelling, the enslaved people gain their freedom and act as guides for the crew and captain, bestowing grace on a graceless situation in a story of beautiful uplift. Now I am more than an ally; I am an accomplice wanting this story to be true.

Lubaina Himid, Le Rodeur: Exchange, 2016, acrylic on canvas, 183 x 244 cm. © Lubaina Himid. Courtesy: the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Andy Keate

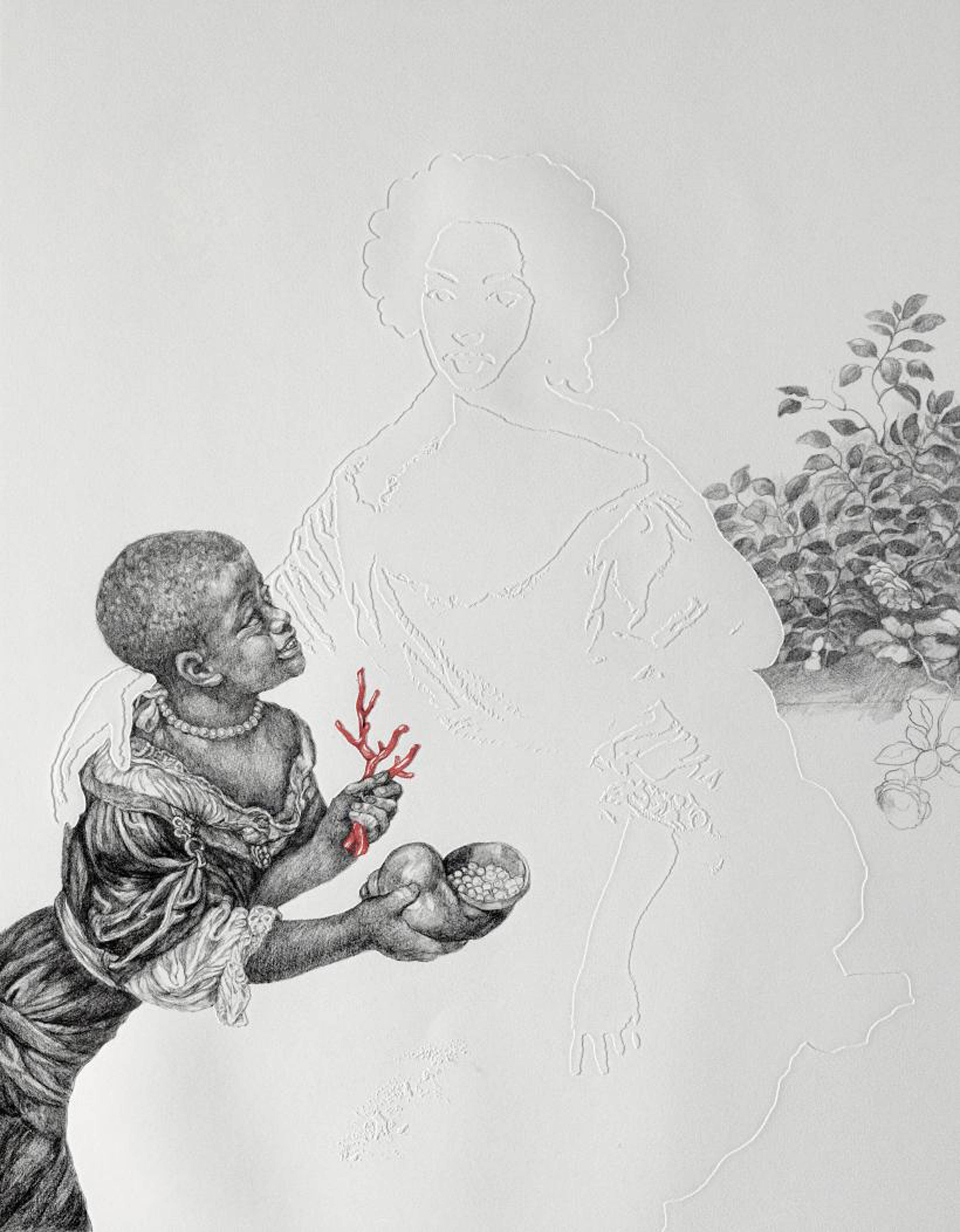

Looking can also be an act of recovery, of resuscitation. Barbara Walker’s drawings of various Black people elided from official accounts make them alive and important, instead of historical footnotes and supporting casts to various dramas. Referring to Pierre Mignard’s painting Louise de Kérouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth, with an Unknown Female Attendant (1682), her Vanishing Point 24 (Mignard) (2021) shows a figure ancillary to a depiction of European royalty now elevated to a kind of punctum, which makes clear the politics and ideologies in the time of the original’s making.

Blackness, as Eshun shares on the walkthrough, is a collective proposition. It’s not the same thing as being Black; rather, it is a worldview and a politics associated with people of the African diaspora that, over time, has become an expected set of behaviors and attitudes. Looking with might signify that viewers are able to relax from the intellectual work of parsing what these images mean. We are not absolved of this work, though; it’s just made collaborative. When I undertake it, I find that Jordan Casteel’s portraits of people in Harlem have the signs of verisimilitude, but are weightless and unconvincing – try looking at them after seeing works by Alice Neel – perhaps because they take their cues from photographs rather than feed off the gravitas of a lived life long observed.

Barbara Walker, Vanishing Point 24 (Mignard), 2021, graphite on embossed Somerset Satin paper, 89.5 x 74.6 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Cristea Roberts Gallery, London

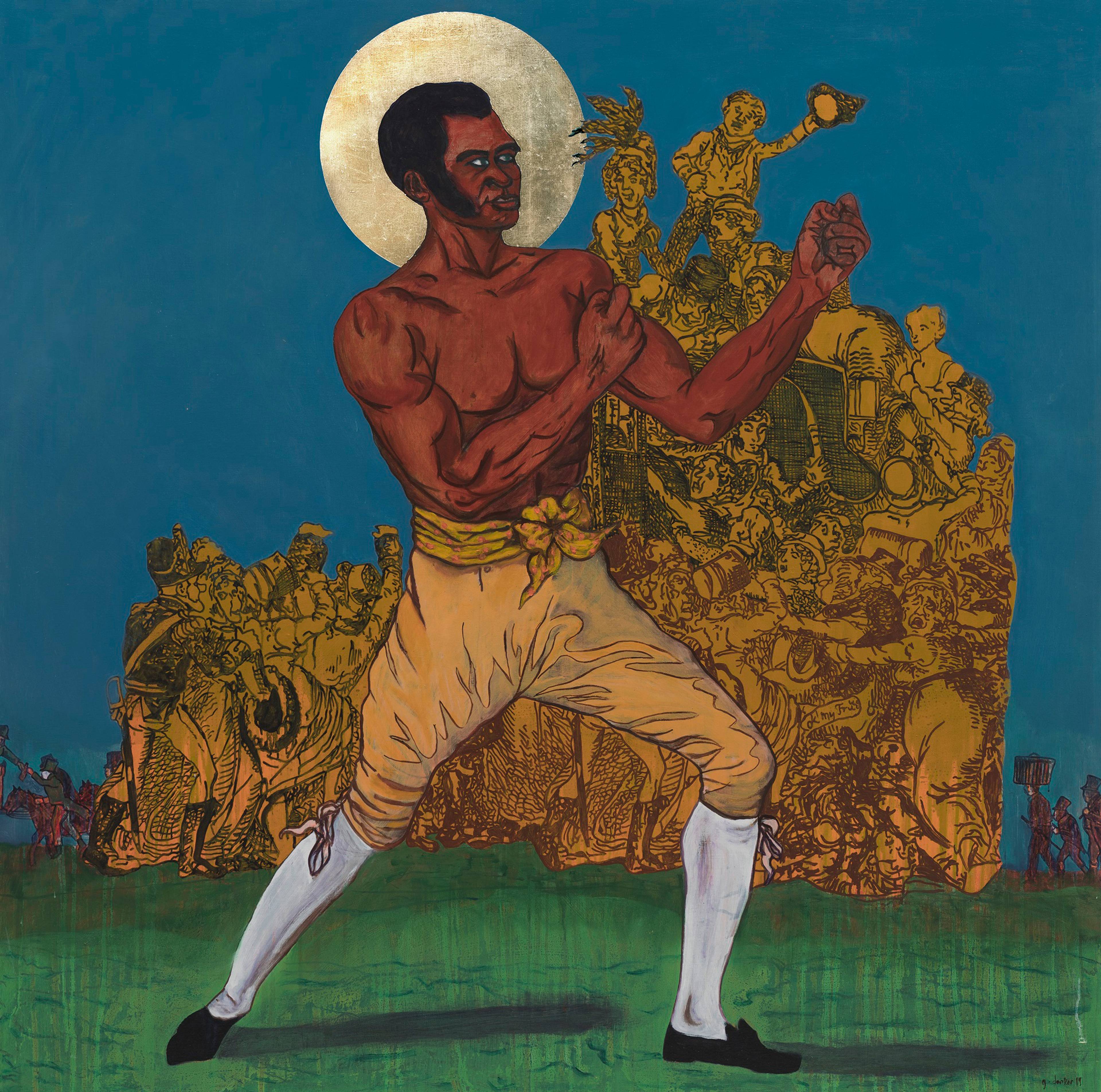

Godfried Donkor, St. Bill Richmond – The Black Terror, 2010, oil, acrylic and gold leaf on linen, 185 x 185 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Gallery 1957, Accra/ London

This show has to contend with the expectation, gathering at least since the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020, that to gesture toward blackness and the whole, complex being of us through portraiture should be enough. It isn’t. Making a portrait, whether loving, speculative, restorative, or documentary, does not mean that its maker, even if they are Black, has fashioned an expansive notion of our being. We are constantly called upon, perhaps more than other races, to look and look again, to question and wonder at the borders we have been born into. “The Time is Always Now” tells me that the work starts here, not with a refusal, blessedly, but with a hand extended to help me feel the import of my being and the being of all those I resemble.

___

“The Time Is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure”

Philadelphia Museum of Art

9 Nov 24 – 9 Feb 25