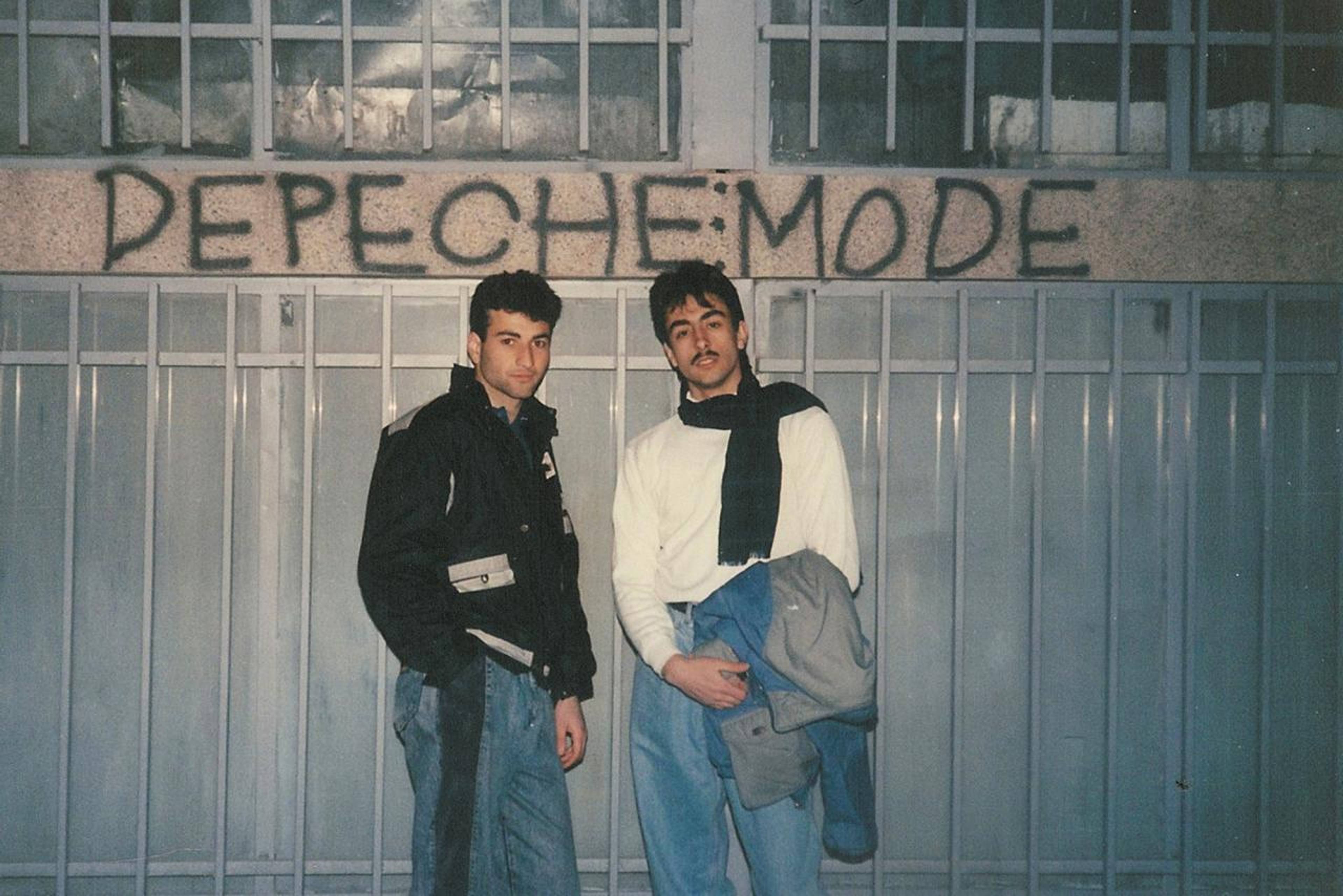

Two teenagers dance to “Never Let Me Down Again” (1987) by Depeche Mode in a parking lot in Pasadena, California, in front of a venue where the band once played. They perform a move fans always do to this number at concerts, waving their arms in the air, simultaneously shy and confident. In his home, one of them, Orlando, shows the camera a collage he has made from pictures of the band glued up on a piece of cardboard and placed on a shelf like an altar. “I have a rose here, and incense,” he says. “You know … devotion.” These scenes, capturing the allure and the moving quality of amateur dancing and fandom as such, are part of Jeremy Deller’s (*1966) Our Hobby Is Depeche Mode (2006), one of several documentaries included in “Welcome to the Shitshow!” a retrospective mounted at Kunsthal Charlottenborg in collaboration with the documentary film festival CPH:DOX. The exhibition, which combines photographs, texts, posters, paintings, banners, films, and an opening-day, eight-hour-long music documentary program curated by the artist himself, is thematically stuck together by music culture, mass political movements, and British heritage and identity.

All the films on view share a hypnotic quality that make their runtimes disappear. In The Height of Goth: 1984: A Night at the Xclusiv Nightclub: Batley, West Yorkshire, UK (1984), produced by club owners Ann and Pete Swallow, New Romantics with mullets and crop tops make dramatic gestures to the tune of Bowie songs, while Jean-Paul Goude’s A One Man Show (1982) meshes music videos with concert footage of Grace Jones, her dancing powerful, angular, and deliberate. Wattstax (1973), directed by Mel Stuart, intersperses footage from the music festival of the same name, held as a benefit concert on the 7th anniversary of the 1965 Watts uprising against racism and police abuse in Los Angeles, with interviews of Black Americans, capturing music’s foundational role in community-building and collective political consciousness.

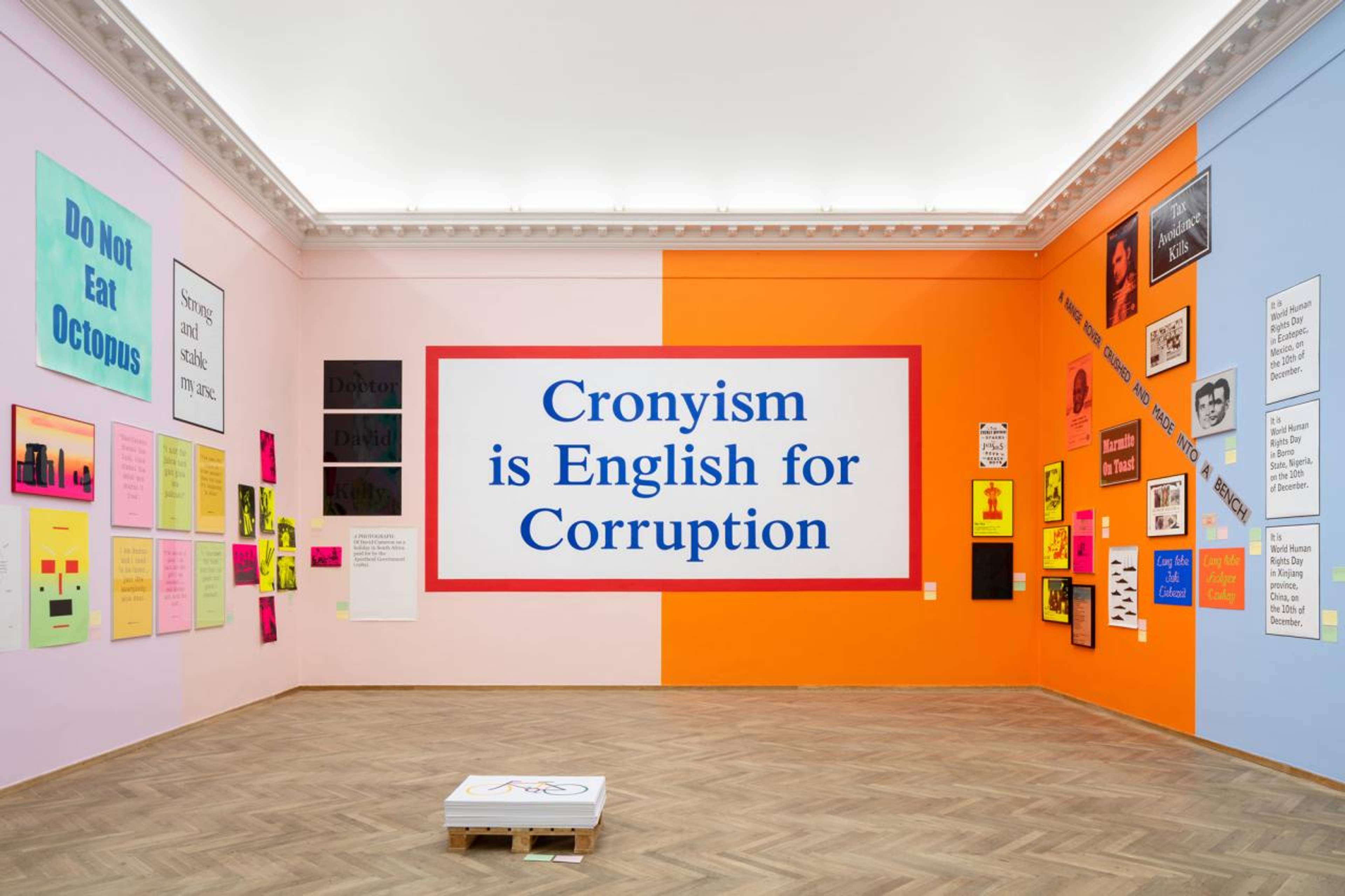

View of “Welcome to the Shitshow!” Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, 2023

The juxtaposition between the documentary program and Deller’s own films poses questions as to what music and movement can do in the world. Deller is an incredibly skilled documentarian, making space as an interviewer for people to articulate what wildly different things a band or a movement can mean: For a young woman in the US, Depeche Mode is an unrequited crush; a man from Teheran explains that the gender ambiguity his celebration entailed was prohibited and violently punished by the Iranian regime; and a group of Russians rejoice that lead singer Dave Gahan was born on Victory Day, which commemorates the Soviet defeat of Nazi Germany on 9 May 1945.

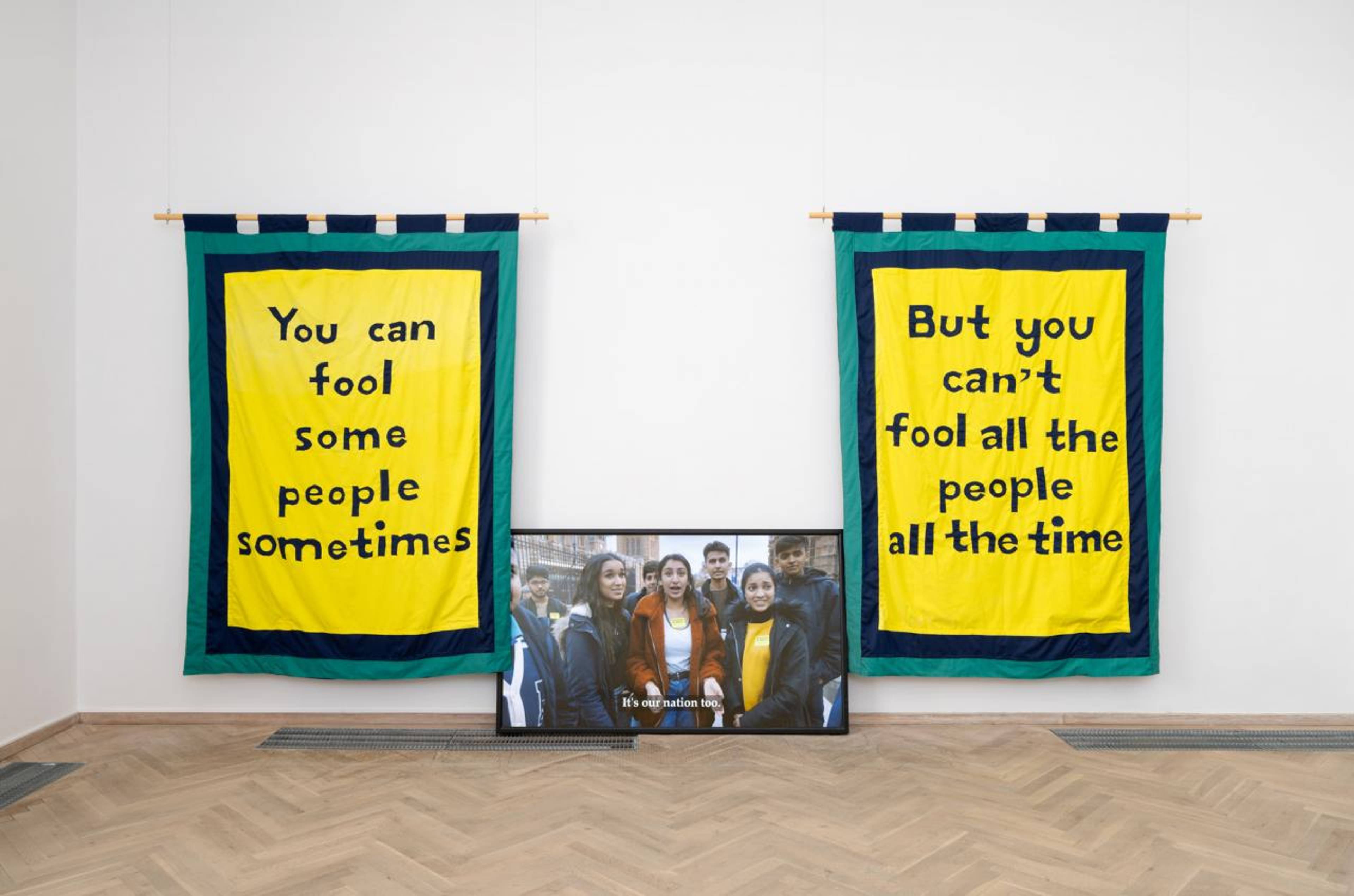

Deller seems interested in the liberatory as well as violent potentials of moving in unison, especially in relation to British identity. Putin’s Happy (2019) interviews demonstrators for and against Brexit – with the former at one juncture singing the imperial naval anthem “Rule, Britania!” (1730) – while English Magic (2013) depicts a parade celebrating the Lord Mayor of London, overlayed with a steel-drum version of David Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold the World” (1970), whose lyrics – “Who knows? Not me / We never lost control” – effectively reflect a glory-days denialism. Both films depict pageantry celebrating and re-actualizing nostalgia for a colonial and supposedly more prosperous past.

Jeremy Deller & Nick Abrahams, Our Hobby is Depeche Mode, 2006

Deller is an artist intensely preoccupied with the reverberations of the past – or fantasies of the past – on the present; even a clip from English Magic that features an inflatable Stonehenge as a playful refuge for children, suggestive of a space for a British future, reveals itself halfway through to be played in reverse. Peppered throughout Deller’s works – as well as in hand-written notes and wall-hung quotes by the artist that frame “Shitshow!” – there is at the same time an apparent devotion to the canonized rock stars of the 70s and 80s. The works move between playfully – or perhaps ironically – reiterating British pop cultural celebration, and what feels to me like earnest veneration of the rock genre . Warning Graphic Content (1993–2021), a large-scale installation of prints, posters, graphic works and photographs, includes a handwritten note calling the band Roxy Music a “highpoint of Western civilization”; lyrics by Bowie, Nirvana, Happy Mondays, and Morrisey framed like Bible verses; and a poster that asks, “What would Neil Young do?” Where Deller’s introductory text to Putin’s Happy asks how “the land of the Beatles” could vote for Brexit, one wonders if it should be understood ironically and how it sits in proportion to the historically deeprooted longing for British domination that the film itself portrays. The icons of yesteryear are seen from afar, invoked as images, gospels, catalysts, raising the politics of hagiography as both form and thematic. Their allure is a dependent function of the distance necessary for projection, certainly; it’s not apparent, though, what exactly we should read into them, nor if the rock stars ever could save England from itself.

Jeremy Deller, You can fool some people sometimes, 2019; But you can’t fool all the people all the time, 2019; and Putin’s Happy, 2019. Installation view, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, 2023

Jeremy Deller, Monarchs of the Glen, 2014. Installation view, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, 2023

“ Welcome to the Shitshow! ”

Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen

16 MAR – 6 AUG 2023