Amid a decade-long resurgence of far-right nationalism in Europe and Israel, Yael Bartana (*1970) has gained international acclaim for video, sculpture, and photography that cuts across the cultural production of personhood and national identity. Her video trilogy “And Europe Will Be Stunned” (2007–11) immerses viewers in the visual language of redemptive nationalism, crafting a narrative around a fictional “Jewish Renaissance Movement” in Poland. The film installation Malka Germania (2021), meanwhile, revisits the historical sites of Berlin’s postwar Erinnerungskultur (memory culture) and their resonances with contemporary debates on Israel-Palestine. Most recently, she opened half of the German Pavilion in Venice (alongside theatre director Ersan Mondtag) with Light to the Nations (2022–24), an eerie, polished multimedia installation about a Kabbalistic spacecraft traversing the cosmos, clothing Jewish messianism in the aesthetics of German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl. As earthly calamities and political dead ends pile up, Bartana’s work looks to space for a way out – before troubling the very basis of exodus.

Hanno Hauenstein: How do you approach art these days?

Yael Bartana: Despite the catastrophic time we are all witnessing, and despite the tendencies in the art world to be very politically polarized, I try to create artworks that take risks, allow for ambiguity, and avoid binaries.

HaH: How should we understand your recent contribution to the exhibition “Thresholds” at the Venice Biennale’s German Pavilion?

YB: If we understand thresholds as passages between territories, categories, and realities, then this is what my works always dealt with. Perhaps my central work in the pavilion, Light to the Nations, can be understood as a means to overcome the final, earthly threshold.

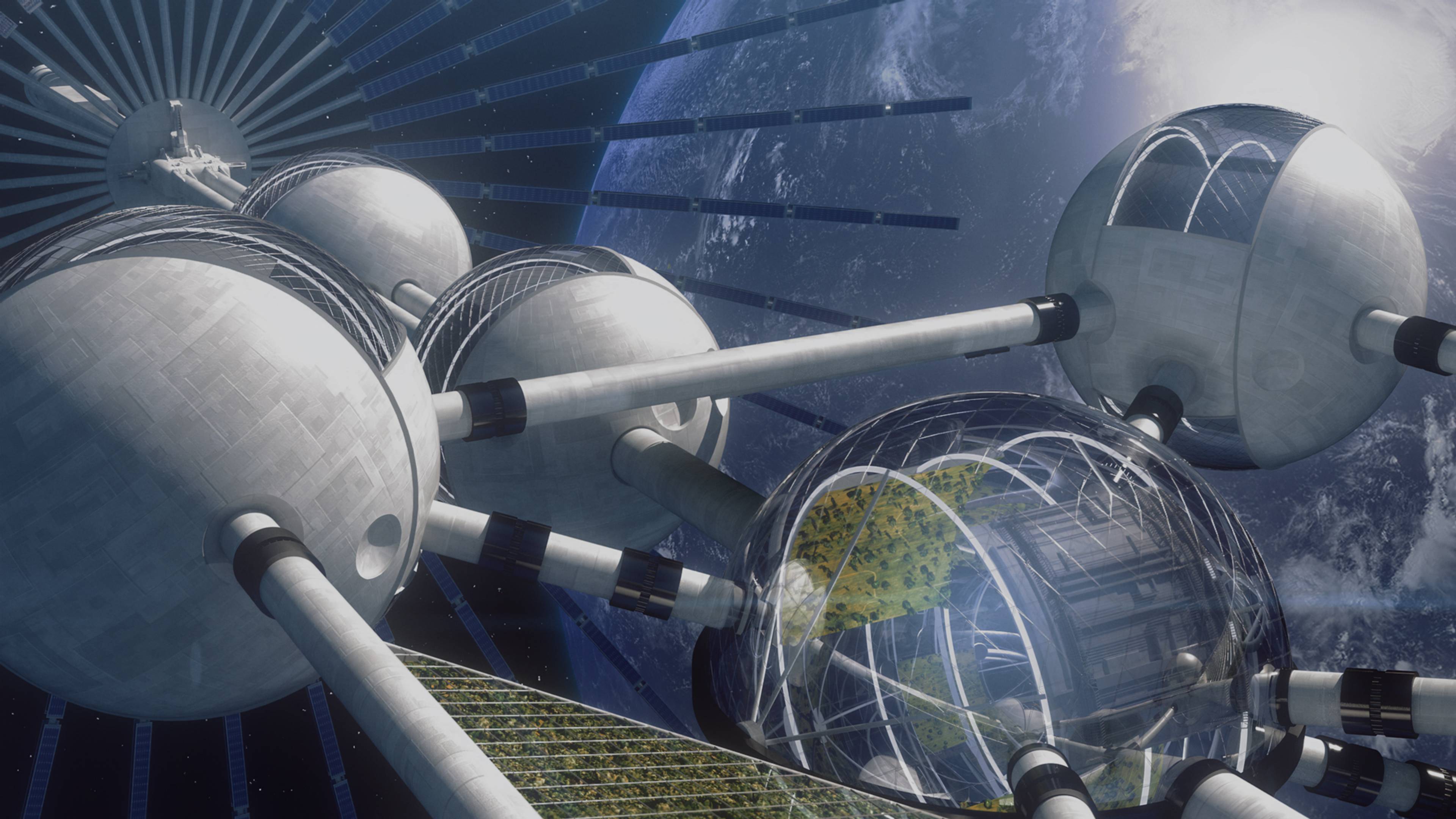

Stills from Yael Bartana, Farewell, 2024, single-channel video, 15:20 min., as part of Light To The Nations, 2022–24 . Courtesy: the artist

HaH: Can you tell me about the genesis of the work?

YB: Light to the Nations is a project I began developing two years ago and first exhibited last year, at the Center for Digital Art in Holon, Israel. Like many of my recent projects, it’s motivated by the piling up of political and environmental crises, the constant feeling of alarm, and is the logical next step in proposing alternatives to our current political imagination. The overarching idea is of saving and striving to improve humanity aboard a generation ship – a hypothetical, interstellar ark that travels for decades at a time. This raises a lot of questions about this contemporary generation’s heritage: Who will be selected to board the ship? How will the social structure aboard function? While we may have a sense of how it will begin, its future remains uncertain – it’s a utopian idea with an inbuilt potential for dystopia.

HaH: And it’s title?

YB: It’s a Biblical phrase from the Book of Isaiah: “I will appoint you to be a covenant for the people and a light to the nations [Or Lagoyim]” I took this call for leadership as a kind of leitmotif for building the spaceship, with a design based on the diagram of the ten Sefirot from the Kabbalah. I drew inspiration from Jewish mysticism, science fiction, and contemporary technology, especially through my discussions with the art historian Doreet LeVitte-Harten.

HaH: You have often explored messianic figures in your work, as well as “Jewish renaissance” and redemption. What drew you to outer space?

YB: For many years, I’ve looked at the concept of the messianic moment – something that generates hope and whose historical repetitions can serve as a vehicle for redemption. The spaceship can save humanity and our planet, which might be better off without us. But, like all grand plans, it must grapple with the weight of history, trauma, and the complexities of reality. It’s also a problematic getaway, full of the dangers of colonial history.

I believe art can help us reflect and challenge the binaries of political agendas, even in the worst of times.

HaH: So, is it a particularly Jewish spaceship, or rather a universal vision of human salvation?

YB: My artistic vision always emerges from my own Israeli identity, which is rooted in Jewish culture. Exhibiting this work in the apsis of the pavilion, built as it was by the Nazis, and having previously featured works by artists like Arno Breker, lends it a sense of irony. Even if the concept is essentially an extension of Jewish narratives of exodus, I imagine there being many other generation ships. For me, space symbolizes the ultimate diaspora.

HaH: How does Light to the Nations treat contemporary political issues?

YB: The first thing that comes to mind is the Jewish idea of Tikkun Olam (Hebrew for “repairing of the world”), that is a key part of the Kabbalah, the responsibility of the mystic. I’m employing this concept as a metaphor: If humanity survives and many other ships follow, the Earth will have an opportunity to heal itself. At the same time, it is impossible to ignore the fact that it addresses the current crisis in the Middle East and, yet again, the Jewish question: Where do we belong? Where can Jews be safe? So, in a way, it is both altruistic and personal.

HaH: Given current debates and the historical significance of showing your work in the German Pavilion, to what degree do you care how different audiences might engage with your artwork?

YB: I’m actually very curious about how the audience will continue to read my proposition. I’ve found that every presentation, both before and after 7 October, has evoked a whole array of experiences and reactions from people.

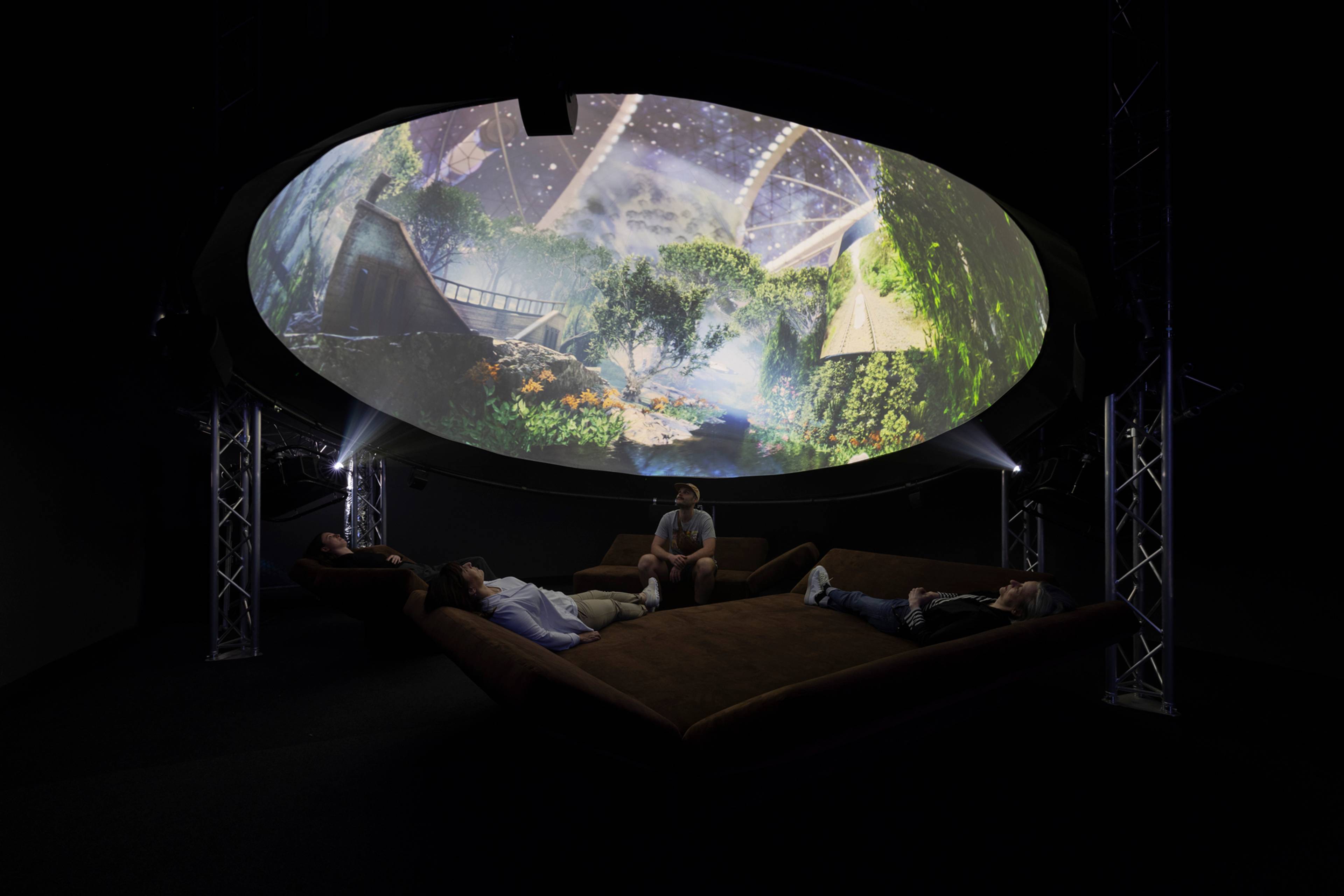

Yael Bartana, Light to the Nations, 2022–24. Installation view, German Pavilion, 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, 2024. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Andrea Rosetti

Yael Bartana, Light to the Nations, 2022–24. Installation view, German Pavilion, 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, 2024. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Andrea Rosetti

HaH: Can you give some examples of what the reactions were like during the opening?

YB: Many people asked if I could reserve them a spot on the generation ship. That made me laugh. Some were upset that I supposedly want to save only the Jews, and others disregarded the complexity of proposing such a “solution” in this specific location and saw in it just another science-fiction story; but most of the reactions were wow.

HaH: You represented the Polish Pavilion in Venice in 2011, and now you’re representing the German one. You’ve never represented Israel. Is there a reason for this?

YB: I wouldn’t say that I am representing Germany, but rather that Germany presents my works, along with those of other artists. The Polish Pavilion made sense because the project I was working on tackled Polish nationalism. With the German Pavilion, when the curator Çağla Ilk asked me to participate, I knew I wanted to show Light to the Nations, in a place where similar redemptive fantasies were played out in the past – and ended in catastrophe. We know that when the idea of utopia is in the wrong hands, it can be very dangerous.

I am not sure I can make a rule regarding where I would like to show my work. I certainly don’t feel like I am a representation of Israel, either, and for the past twenty years, I have deliberately not applied to exhibit in its pavilion, as I have not felt at ease with that idea. But I hope this might change.

I do wonder what this current work will bring to mind, particularly given where it’s shown: a spaceship in a Kabbalistic shape that saves the Jews.

HaH: How did you perceive the public discussions around the Israeli Pavilion over the past seven months, in light of Israel’s war in Gaza?

YB: The war in Gaza and the Israeli hostage situation are horrifying, and I understand the need to position oneself, but I don’t believe in boycotting art or artists. My approach has always been to make things more complex, to tap into the places that are uncomfortable and to keep asking questions, as I believe art can help us reflect and challenge the binaries of political agendas, even in the worst of times.

HaH: Ahead of the Biennale’s opening, the Art Not Genocide Alliance, a collective of cultural workers, artists, and activists, circulated an open letter calling for a boycott of the Israeli Pavilion amid the ongoing killing of Palestinian civilians in Gaza. It was signed by some prominent artists, such as the photographer Nan Goldin. What did you think of this?

YB: People should make statements! At the same time, I am wary of attacks on individual artists. There can be no question that Hamas does not represent all Palestinians, just as the state of Israel, particularly its current government, does not represent all Israelis. I think it’s important that we keep differentiating between states and citizens on both sides.

Protest organized by the Art Not Genocide Alliance during the opening of the 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, 2024

Artist’s and curators’ statement in the window of the Israeli Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, 2024

HaH: What did you make of the decision of Ruth Patir, the artist representing the Israeli Pavilion, not to open her show to the public – until a ceasefire and hostage-release agreement is reached?

YB: Every Israeli artist right now is under pressure to take a stance, and everyone I know wants a permanent ceasefire and the hostages released. The artist and curators have my respect for taking what must have been a very tough decision.

HaH: In previous editions of the Biennale, there have been discussions about abandoning the national pavilions altogether.

YB: The concept is quite outdated, but it is more flexible than people imagine. When I represented Poland thirteen years ago, I did so precisely to find a way to challenge the model of the nation-state. This time around, Çağla had a wish to deterritorialize the German Pavilion, which I feel my project supports.

Yael Bartana, Light to the Nations, 2022–24. Installation view, German Pavilion, 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, 2024. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Andrea Rosetti

HaH: What do you make of the cancellations, restrictions, and even travel bans that numerous individuals in Germany’s cultural sector have faced for their criticisms of Israel, specifically its incursions on Gaza and the dozens of thousands of Palestinians killed in this process?

YB: The cancellations worry me deeply, as they indicate that the public sphere in Germany is narrowing. If Germans really do want to live in a democracy, there needs to be space to speak out, without fear that individuals will be targeted in this way. Many have said this before, but I do believe that the specific context, with Germany’s past and its relation to the state of Israel, plays a problematic role. We need multiple voices, also contradicting each other, to keep arts and culture vibrant and relevant.

HaH: How important is Jewish history to your work generally?

YB: My artworks are intertwined with my identity as an Israeli Jew who spends a lot of time in Germany, Netherlands, Scandinavia, Italy, and the rest of Europe. Sometimes, people have a hard time understanding why, for example, I dress up like the founder of Zionism, Theodor Herzl, in some of my self-portraits. I like to investigate the Zionist imaginary and how it connects with other periods in history, specifically in Germany. But I do wonder what this current work will bring to mind, particularly given where it’s shown: a spaceship in a Kabbalistic shape that saves the Jews. After all, it is a kind of final solution – just not in the way Germans are used to thinking about this term.

HaH: Has your own perspective on Light to the Nations changed since 7 October?

YB: For many people, it is difficult to see the work and not think about 7 October and what followed, and that’s okay. Unfortunately, the recent horrific events have made my spaceship feel almost prophetically necessary. This project follows my work What if Women Ruled the World? (2018), which dealt with an imminent nuclear threat a few years before Putin invaded Ukraine and globally re-tabled the fear of nuclear war. In a way, it demonstrates art’s potential to predict, but also to challenge the future.

Portrait of Yael Bartana, 2024. Photo: Daniel Meir

Yael Bartana, Herzl III, 2015, photo series of six images. Courtesy: the artist

___

“Thresholds”

German Pavilion

60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia

20 Apr – 24 Nov 2024