I was seven years old when I hit the jackpot. After weeks of staking out the gumball machines at the local grocery store and cadging nickels from my parents at every opportunity, I had a plastic capsule in my hand and in that capsule was my new mascot: a hairy, rotund figure with popping eyes, a feral grin, notched ears, and patched overalls with the letters “R.F.” appliqued to the front that identified what my new treasure was: a Rat Fink.

Created by car customizer and counter cultural anti-hero Ed “Big Daddy” Roth in 1963, Rat Fink was a character initially conceived as an answer to the oppressive blandness of the 1950s iteration of Mickey Mouse. In place of Mickey’s smooth, rounded outlines, staid family-friendly success, and suburban leisure clothing, The Fink is all jagged lines and antisocial aggression. He looks like he smells bad, even if you don’t notice the flies buzzing around his clearly un-washed feet. He’s probably a speed freak in both senses of the term. The card that was stuck to the front of the gumball machine was a marvel of advertising: a group of Rat Fink key fobs are surrounded by phrases like “I’M SLOPPY,” “I’M VICIOUS,” “I’M SELFISH,” “I’M DIRTY,” “I’M DANGEROUS,” “I’M NASTY,” the whole thing surmounted by the phrase “RAT FINK: That’s Me!” Seven-year-old me could not resist that siren call, somehow sensing that I had more in common with the monstrous rat than the milquetoast mouse.

Every notion of progress, whether it be social or aesthetic, creates the possibility of its shadow at the moment of its conception. That shadow, composed of everything that “progress” must repress to assert its own positivity, resides within culture as a place of potential power, a location that can correct the stupidity and brutality that often walks alongside forces of “progress.” The flush of economic power that the United States experienced in the aftermath of World War II jump-started a positivist cultural imperialism built on extravagant consumer culture and social conservatism. American capitalism positioned itself as the antidote to global communism as well as all kinds of social deviance. American automobiles in particular were advertised as symbols of freedom, virility, and triumphant individuality, in spite of them merely being mass-produced, mass-marketed commodities. And these symbols of supposed progress called forth their shadow: a counterculture of the customized, the antisocial, the hybridized, and the monstrous.

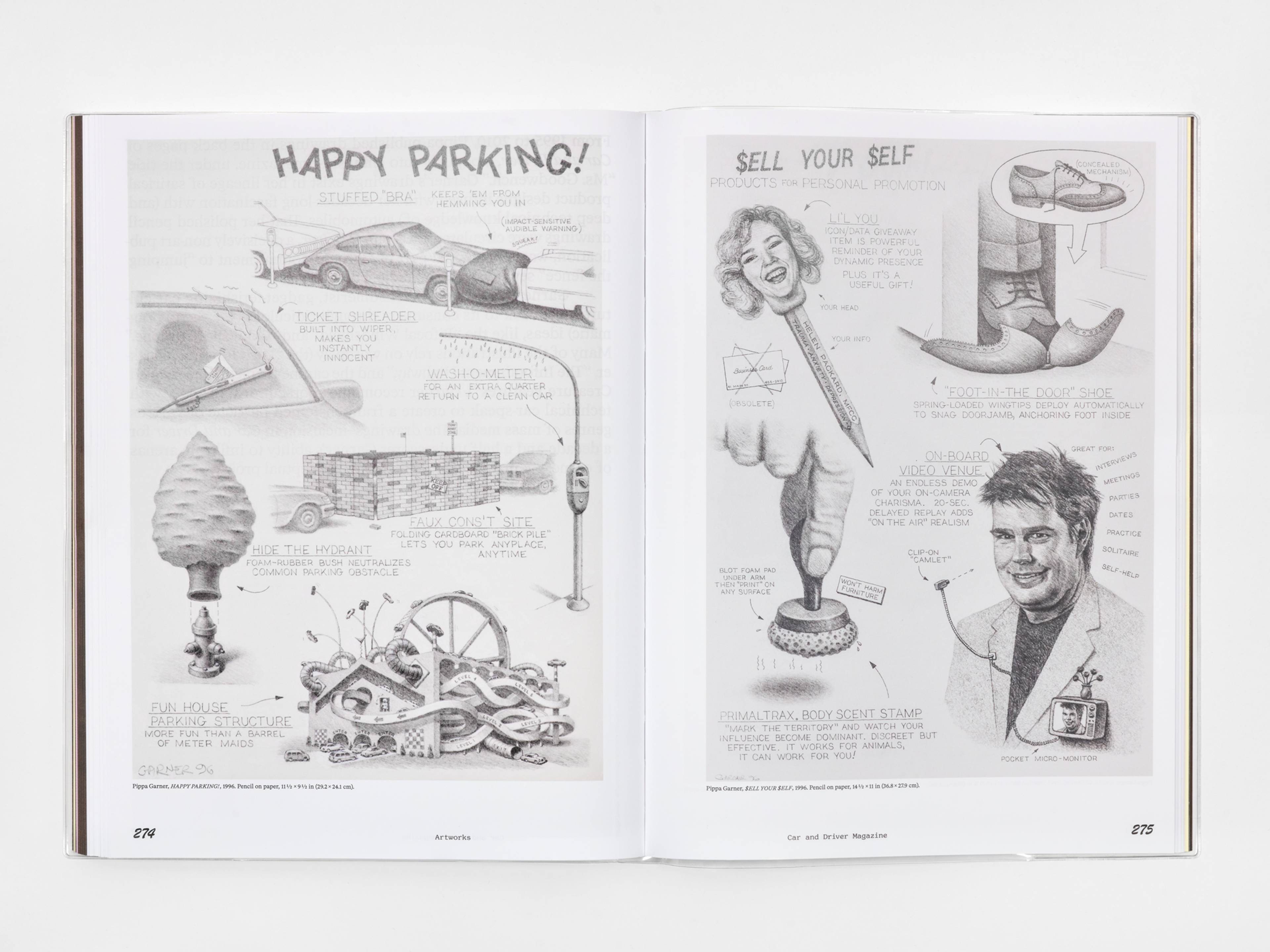

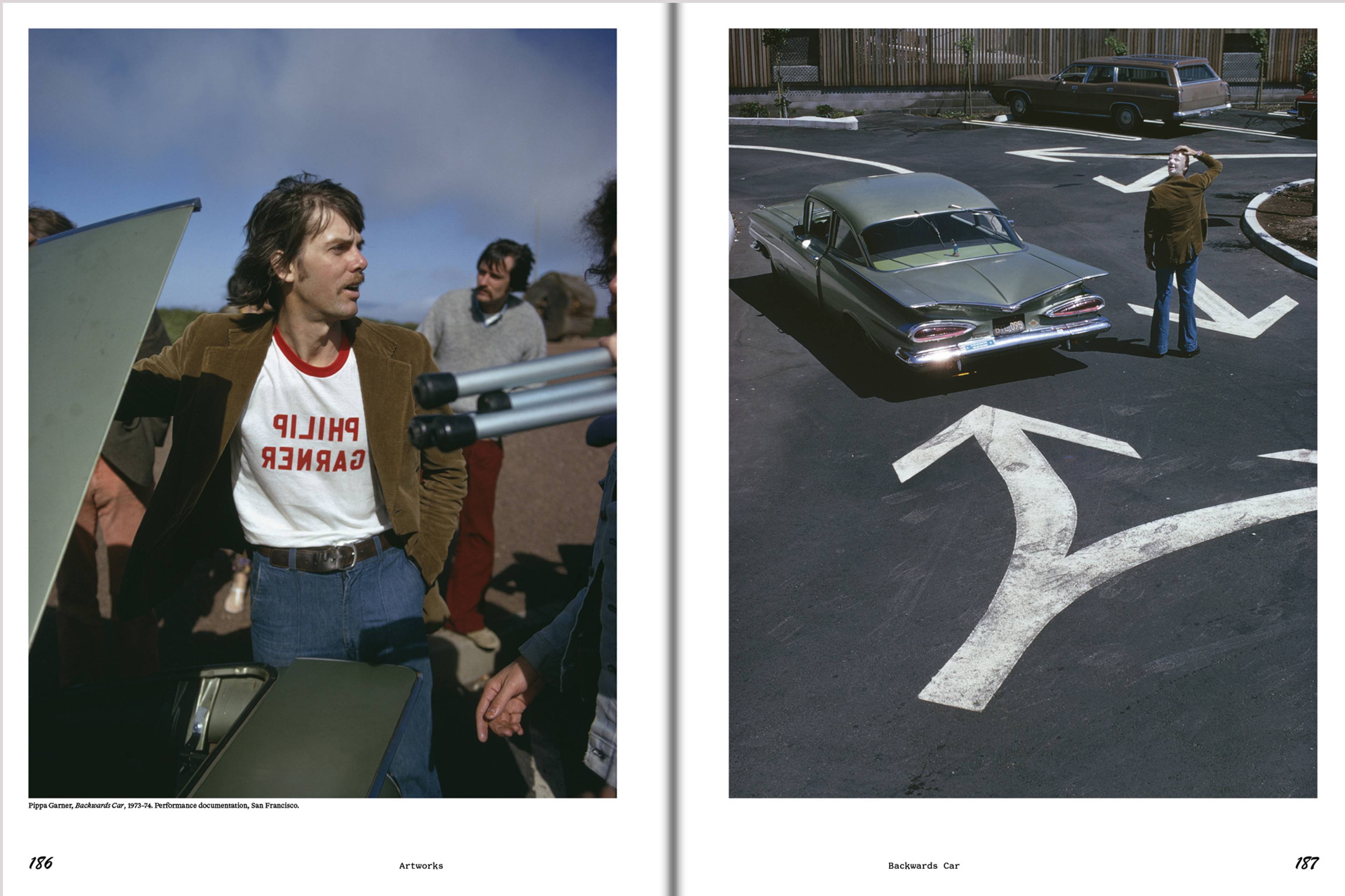

Spread from Pippa Garner: $ELL YOUR $ELF, 2023

Spread from Pippa Garner: $ELL YOUR $ELF, 2023

Custom car culture was the freaky, dirty reaction to the gloss of American consumerism. It was handmade, un-shaven, and misshapen, created by ne’er-do-wells in greasy garages who pillaged old junkers and created rococo missiles out of the parts they found there. Custom car culture was twinned with the rise of “sick culture,” the impulse that mostly played out in comedy and print media, encompassing creators like Charles Addams, Basil Wolverton, Lenny Bruce, and many more. Sick culture was surrealism’s pop culture wing, delighting in monsters, grotesque bodies, and goofball cynicism. Mad magazine was its most visible publication, trailing in its wake imitators like Cracked, Thimk, Help!, Frenzy, and Humbug. Big Daddy Roth was the figure that forged the connection between custom car culture and sick culture, creating visions of goon-eyed hot rodders whose bodies were as weird as their wheels.

The counterculture of the 60s and 70s produced its own narratives of progress, built around bodily autonomy and liberation. In a funny way, the monsters of sick culture were tamed and mellowed into hippies for whom progress required nothing more than the twinned platitudes of Peace and Love. The possibilities of social revolution postulated by the New Left, the civil rights movement, and the women’s movement all were absorbed and transmuted into new varieties of soothing consumerism.

The commonality running through and linking all these developments is the sophisticated burbling of America’s most evolved cultural language: advertising. Since the Second World War, American advertising has worked to sell the world on visions of prosperity, safety, stability, and conformism couched in a rhetoric of individualism. It has called for change, as long as change meant continuing to buy the same stuff. It has preached “togetherness” as an antidote to collective action, and has sold jeans, cigarettes, shotguns, and computer operating systems all called “Maverick.”

If you sell a car as just an extension of a guy’s dick, she asked, why not a car with a dick?

Enter Pippa Garner, child of an ad man, whose early life reads like a training course in mainstream identity: midwestern childhood, employment in an auto factory, stint in the military, college for auto design, job as illustrator for Car and Driver magazine. And yet … while steeped in the language and locations of advertising, Garner man-aged to see the shadows it birthed. As she says in an interview from 2021: “The advertising, consumerism, in the background in my life, was very much gender-oriented. There were things for women and things for men. It was all-out masculinity or all-out femininity, macho or made up. And if you didn’t feel that yourself, you felt uncomfortable. That was what they wanted, so that you would buy their products.” She saw the outfit that society had measured her for and knew that it didn’t fit.

To begin with, she used the tools and language of mid-century American consumerism to call forth the monstrous and hybrid. She started customizing cars. Her approach was markedly different from that of the detailers and hot rodders of an earlier generation. The Southern California scene, for all of its macho bluster, produced cars that were as camp as the outfits of any drag queen: acid yellow candy-flaked curving bodies topped by plexi domes and dripping with chrome, flame jobs as carefully applied as any shadow and eyeliner. In contrast, Garner’s vehicles present as midwestern butch. If you sell a car as just an extension of a guy’s dick, she asked, why not a car with a dick? That proposal didn’t go over well at automotive de-sign school: they expelled her. She took on the identity of a tinkerer, a putterer, a customizer whose subversions could pass as mere eccentricities: “Hey that idea’s so crazy it just might work!” Watch her deftly deadpan her way through an interview with that pillar of the American mainstream, Johnny Carson, presenting a series of gadgets that solve problems that, on further reflection, are all problems of gender, alienation, loneliness, and social anxiety. Her patter is quiet and reserved: she’s not pushing for jokes, she’s letting the ideas do the work. (Now imagine what she could do with that temple of entrepreneurial pomposity, Shark Tank.) Her work at this point seems to me to be related to several other strains of subculture that employed similar imagery, like the Church of the SubGenius and Devo.

Spread from Pippa Garner: $ELL YOUR $ELF, 2023

Spread from Pippa Garner: $ELL YOUR $ELF, 2023

If I can customize my car’s body, then why can’t I customize my body? It’s a simple question and Pippa was not alone in asking it. Throughout the 1980s several communities converged around the idea of body modification as performance art, spiritual quest, or personal adornment. In the Bay Area these explorers overlapped with the expanding tattoo culture and the leather scene, an interaction documented in the RE/Search publication Modern Primitives. Most of these modifiers weren’t thinking about gender, and even though there was an increasing number of visible trans people, they were discussed as being in transition from one side of the gender binary to the other. The idea that it might be possible to walk away from the binary altogether was rarely brought up until the next decade, when the concept of gender as performance began to gain purchase.

Pippa brought a customizer’s sensibility to the problem of her gender, experimenting with her body’s chemistry, looking at surgery and tattooing. Creating a new self. In this sense she is her most utopian work. But every utopia spawns a shadow, and it is the way that Pippa has voiced that shadow that moves me most. To understand that, we need to return to advertising once again.

Behind every physical thing that advertising encourages you to consume there lurks another thing it is trying to sell you: the notion that your self is something that expresses its essence through the act of consumption, and not through the act of creation. This conflation of selfhood with consumption is a sophistry so pervasive that it allows people to measure their social actions in relation to what they term their “brand.” We have internalized capitalism’s transactional ontology so completely that we become willing advertisements for ourselves and by extension our communities. And so we get The Minority Role Model, precursor to, among other nightmares, The Influencer. Minorities are offered the chance for the basic human dignity they are owed, so long as they behave themselves and spout the same positivism as the mainstream. They are supposed to inspire with their courage, overcome the odds, express gratitude for the scraps.

How do we demand what we want when all we can use is the debased language of advertising, and we know how debased that language is?

Like any sensible monster, Pippa rejects that position too, refusing to be looked up to, refusing to repackage her pain and desires into uplift and inspiration. My favorite works of Pippa’s tackle this state of affairs directly: How do we demand what we want when all we can use is the debased language of advertising, and we know how debased that language is? I’m talking about the series of personal ads she posted in several alternative weeklies since her transition and the sloganizing T-shirts she continues to make. These ads bounce between disdain and desperation, exuberance and raucous humor, all in the space of a few well-turned phrases:

SEX CHANGED DEVIL GIRL

I AM the battle of the sexes – the worst traits of man and woman convoluted into one demented soul. Step into my lair and you are lost irretrievably. Even reading this is dangerous. Yummy, slurp!

This is masterful writing, and as wonderful a piece of gender demolition as I have ever encountered. In these pieces Garner reveals the inadequacies of another positivism, one based in her position as a trans woman. She refuses to settle for being a role model and demands that the world meet her terms. It’s as if Rat Fink asked me out on a date and daring me to be worthy of the honor.

That Pippa tinkers with her gender to please herself is her greatest power. That she is self-satisfied, remaking her body and herself as she sees fit, while retaining her skepticism regarding all organized positivism, is the thing that makes her work even more important today. Her choices and her honesty about those choices remind me of the difference between real human autonomy and the manufactured non-choices dished up by our contracting society. Pippa is irredeemable. That makes her precious.

View of “Pippa Garner: $ELL YOUR $ELF,” Art Omi, Ghent, New York, 2023. Photo: Gregory Carideo

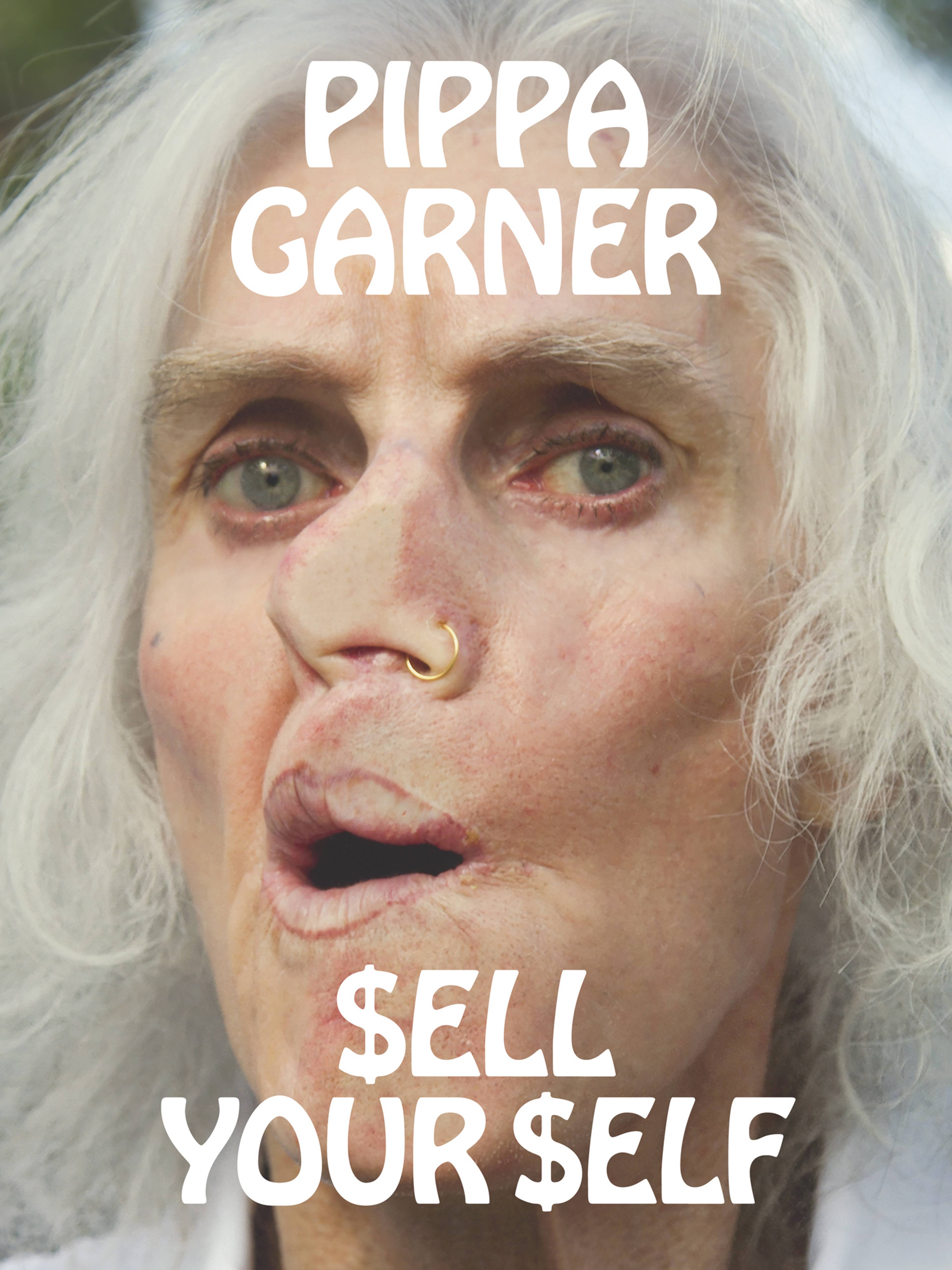

Cover of Pippa Garner: $ELL YOUR $ELF, 2023

___

This essay was originally commissioned for and appeared in the 2023 monograph Pippa Garner: $ELL YOUR $ELF, published by Pioneer Works and Art Omi.