Wayne Koestenbaum (*1958) is Mother. Or is it Zaddy? Daughter, perhaps. Certainly teacher – unconditionally – of the mutually transformational kind. I was his student, and like so many others who both were and were not his student, am deeply influenced by his sense of unbridled experimentation, a release into divagation and errancy that is only matched by the precise plumb line of his style, undulating from arched back to poitrine en dehors (chest out) in a mere half-breath. Mother, who is the author of twenty-three books and counting, has taught so many of us what we know: how to swerve unceasingly from one genre to another, frotting categories (mis)classified as fiction, cultural and film criticism, theory, biography, self-writing, personal essay, poetry, performance (it is all performance), music, painting, collage, film, and a ceaseless more. All the while, he trusts the faultiness of words to find a way to describe the ineffable, using everything at his disposal to be there with us through the language of observation and what lies beyond.

Thomas Lax: Wayne, in your film The Gays [2023], you mentioned that, back at RKO Pictures, it was [Marlene] Dietrich who taught you German, including the conjugations of tenses like the future imperfect; how to pretend to be heartbroken; how to braise. What happened in 1915, the year that, in your film, you say the gays got started? Marinetti’s collage of Zang Tumb Tuuum? The Picture of Dorian Gray directed by Eugene Moore? This is my citational way of referencing your use of found sound as a kind of collage – a layering of accident – as well as the eternal youth that animate your films, as if they too were conjugated in the future imperfect.

Also: Tell me about the “arm star” who appears towards the end of the film. Woof. Purr. Bleat.

Still from Wayne Koestenbaum, The Gays, 2023

Wayne Koestenbaum: Dear T.: I love that we’re “leading” with digression: Our film conversation begins with outtakes, “bad” splices.

In 1915, Charlie Chaplin switched studios, from Keystone to Essanay. When I was a kid, I was obsessed with Chaplin, so my cinematic imagination is formed by the map of his career – its palm-lines. The essay – whether in prose, poetry, or film – is my zone-of-choice. “Essay” lodges inside “Essanay,” not trivially. I saw myself, I essayed or Essanayed to see myself, in his vagabondage, his awkward strut, his inappropriate smittenness, always doting on the wrong object.

The arm star: I discovered that resplendent, sun-touched arm, with its evenly arranged tendrils of hair, at a party in Houston in 2018. I filmed the guy’s arm, but forgot to film his face.

The non-diegetic background score to the film of mine that mentions 1915, The Gays, is a spliced-together collage of piano reverberations: I played a sequence of very slow chords on the piano; between the chords, I kept the sostenuto pedal down and let the resonances remain. Composing the collage on the computer, I omitted the chord’s initiations and retained only the diminuendo of overtone, of residue. I stacked up the afterglows.

As a beloved teacher of mine once asked me, rhetorically, “How quietly can you play that passage?” I’m still asking myself that question

TL: I think I picked up leading with digression from you … or was it that it was digression that first brought us together? Time spent with masks on and a more-than-usual desperation for time spent with others. Then and now, the bad splices seem like ways of surfing symptom, getting at what is repressed by swerving directly away from it, forgetting the inconsequential and then returning to it obsessively, looking at the surface underneath the surface, listening to what can be heard from behind your glasses.

I appreciate a Virgo’s commitment to precedent. But would you like to try some of my rhubarb confit? My grandmother used to grow it in her garden, the green and red fibrous stalks, making outside indistinguishable from in.

I’m going to continue down our vagabondage, Essanayons forearm by forearm, repetition the clumsy way in which the vnous (a cross between the first- and second-person plurals that emerged from a Belgian anti-xenophobic campaign to house migrants) will have been conjugated. More stacked residues of piano reverberations.

Your videos seem to be full of koans. For example:

- “Can you tickle everyone in the group simultaneously?” (from The Group Tickling Experiment, 2024)

- “You know cherry pudding, when you forget to remove the pits for the visitor … the visitors?” (from The Window and the Door, 2023)

“Do you want me to call your mom?” (from The Ex-Lovers, 2023)

Stills from Wayne Koestenbaum, Intimacies and Agglomerations, 2024, 3 min.

WK: We met with masks on, and never saw the lower half of each other’s faces until weeks and weeks of serious conversation had transpired. And so, I’m perpetually smitten by your smile, because it’s a lovely smile, but also because it had been hidden and so it still contains (for me) the memory of that hiddenness. Fort-da of a smile: I saw Battleship Potemkin [1925] recently for the first time, and read [its director, Sergei] Eistenstein’s The Film Sense [1957], and though montage is old news, what’s new in montage, for me, is the way it proffers the “treat” (muscle, money-shot, shock) by depriving us of the treat and then bestowing it on us. Montage isn’t about story-telling, it’s about the “slap slap” (or splice) of deprivation/reward, deprivation/reward. The reappearance of your smile, after months of mask, teaches me about montage.

Can you tickle everyone in the group simultaneously? Yes. The primal scene of group tickling is Samuel Delany’s porn-theater-space in Times Square Red, Times Square Blue [1999], the “all-over” painting of what he calls “contact.” (Reimagine Jackson Pollock’s 1952 Convergence as a screen grab of the Adonis theater or the St. Marks Baths.) Contact, unlike conjugality, involves the skittering (the tickling) of members and limbs only glancingly connecting. But reading a book is also a group tickling experiment, as is this conversation, as is every time a poem composed of lines makes up its mind to move to the next line. Eisenstein sees in Milton and other poetic ancients the secret history of montage. Eisenstein’s bisexuality (is that the correct designation?) is itself a montage, the human/animal conjugations of his sex drawings a demonstration of a theory we seem to be constructing, you and I, in this conversation, about the romance of the bad splice.

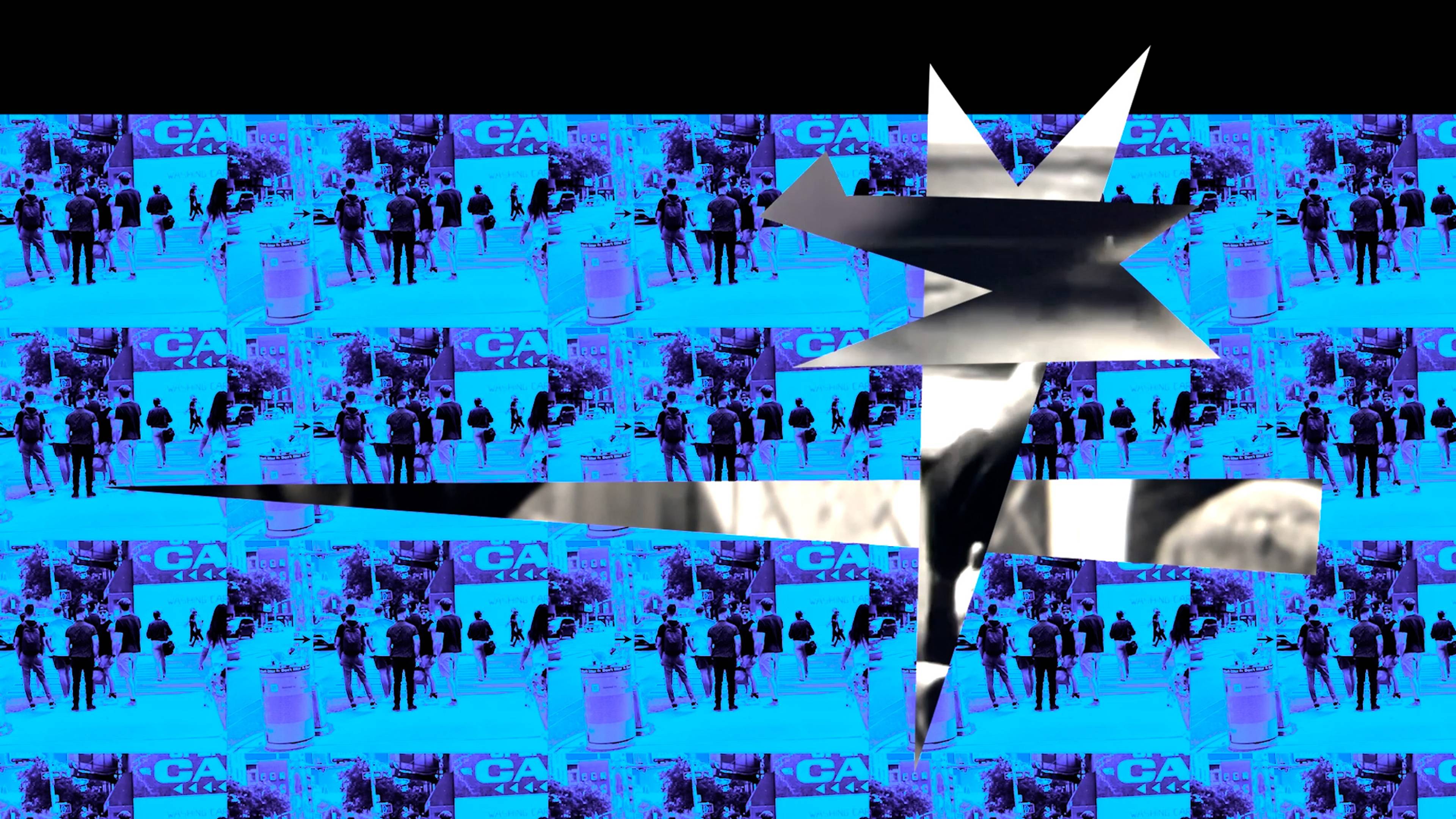

Here’s a pair of stills from a new film of mine, The Only Game In Octobertown. I’m playing my usual character, October Castelnuovo Spielhaus. October, in this shot, is behaving like a bad splice. See how October hangs out in the periphery of the image. See October’s beads, tickling their way into the aperture of your attention.

Stills from Wayne Koestenbaum, The Only Game In Octobertown, 2024, 8 min.

TL: What you say about montage could be said about your poetry, too, but I think that one difference between the slap-slap of your writing and your filmmaking is, perhaps, its spatial logic. If the splice requires you (or, more precisely. your desire) for the suture, the “you” that appears in your films is differently situated – specifically within the space of your studio. This can be explicit, like in the case of The Boy Next Door, which stars your neighbor, the furniture designer William Stuart. But it can also be more allegorical, like in how the stop-motion time of the studio connects the drawings in Intimacies and Agglomerations [2024], or even structural, in the ways that it is in the reflection of your sunglasses, which, like the camera, reveal through inversion, that we know where we are. Style (sunnies!) becomes an expansion of the camera’s internal functioning. Does any of this musing about the studio resonate?

There’s a lot of writing in the history of institutional critique about the studio as linked to other fraught spaces like the museum or the gallery in terms of individuation and the production of the figure of the artist. But I guess what I’m trying to say is that in site-ing montage within the architecture of the studio, there’s a sustained portrait of the intimacy of an ever-multiplying dyad or couplet that you seem to be constructing. I guess this is exactly what you’re saying about montaging yourself onto someone, the gaze built on the assumption of an identity that has already been forfeited. It also feels related to the work of some artists I know are important to you and me, for example, Paul Mpagi Sepuya or Carolee Schneemann, where the setup of the studio is handled, fleshed out in all of its materiality, and thus able to be moved around and manipulated. The work becomes a kind of proxy for putting your hand in someone or rubbing up against another person until there is a more precise way of asking who is who, or as a dear once said to me, which witch is which?

Something else I’ve learned to do in my writing about art is tend towards mimicry, an attempt to translate the voice or style of something I’m looking at or listening to, into an essay form that resembles the thing I’m writing about. “Haptic criticism” is one way the film critic Laura Marks names this. Another way is the kind of indistinguishability that you describe as a gaze that forgets itself. It’s one of the reasons I love Q&As as a genre: They’re an envelope for exactly that kind of call and call, to call on Fred Moten via I can’t remember whom. I share that love with many of your films. I think we’ve taken that boomerang to a horizon here, even as I imagine that, for our readers (hi dear readers!), it is also clear whose click-clack is whose. (No one’s ...) I guess what I’m asking you is, what kind of shape do you think this thing will take? Or, another way of asking this, how do you go about editing your micro-movies?

Stills from Wayne Koestenbaum, The Group Tickling Experiment, 2024, 4 min.

WK: Thank you for reminding me of the coziness of Q&A as genre (I esteem coziness, consider it cousin to the sublime): We are “held” or hugged by the call and response that becomes, echoingly, a call and a call. That’s a way of saying that we are growing to resemble each other, vocally, in conversation, and thereby, as if this interview were a studio space in which we’re performing in a film, we mimic the famous shot from [Ingmar] Bergman’s Persona [1966], identities intertwining.

Thank you for understanding that my studio space, reconstructed and echoed in my films, becomes a disposatif (pace Foucault), but a “cute” disposatif, or at least a fey specimen. I keep rushing to the maypole of the word disposatif with a certain hectic, repetitive desperation and longing, because I misinterpret that word to mean, also, secretly, proscenium and foundation.

My studio, spliced and reflected in my films, is a romance app, as it were, where no algorithms need apply. Everyone’s a “match.” Paul Sepuya’s studio, his understanding of desire as a consequence of the studio, or as the studio’s sequelae, its aftermath, touches me. (Without a studio, even an imaginary one, there can’t be desire, or at least there can’t be desire squared, desire raised to the nth power.) I’ve never been photographed by Paul (except maybe once, in passing, in my studio?), but I learned from him how to look more carefully at faces I desire and to seek in them their secret matteness, their neutrality, like the contact paper you put in a bureau drawer to make it safe for your clothes to rest there.

Reading a book is also a group tickling experiment, as is this conversation, as is every time a poem composed of lines makes up its mind to move to the next line.

Sometimes I regret the reappearance of my own studio in my films (shouldn’t I be seeking out “locations?”), but I accept the fact that, if I want to stage desire’s repetitiveness, the charm and thrill of its slap-slap, then I must remain faithful to my studio as location for the couplings and asymptotes I’m rehearsing.

“Throwing away what has come before”: revolutionary! rejuvenating! arduous! Two current modes in my filmmaking – stop-motion animation and hand-painted, 16mm film – are bygone practices. Returning to these procedures, I’m throwing away progress. I’m throwing away my own era, my own currency. (That’s not the same as regression.) I’m throwing away the notion that past is past. As [poet] James Schuyler wrote [in “Salute,” 1951], “Past is past, and if one / remembers what one meant / to do and never did, is / not to have thought to do / enough?” He opens the poem with an emphatically didactic sureness: “past is past.” But I know he doesn’t mean it. If “past” can be followed by a phrase as serpentine and qualifying as “and if one / remembers what one meant / to do and never did,” then we’re in sticky territory, generatively sticky, a zone where the thrown-out past keeps coming back with boomerang hauntedness.

Still from Wayne Koestenbaum, The Window and the Door, 2023

Still from Wayne Koestenbaum, The Window and the Door, 2023, 3 min.

Haptic criticism is the round we’re singing right now: haptic criticism, a motet for two voices. If I do alto, will you do tenor? Editing our motet will be easy, because we’re behaving with utmost judiciousness and decorum. We’ve veered away from vérité. I’ve lured you into my late style.

I edit my films the same way I edit my poems and my prose. I cut out what I don’t want. I keep cutting. I rearrange what’s left. I superimpose. And then I add new passages to compensate for the ennui that ensues when I survey the wreckage. The secret of adding new passages is that they must be composed in the same taut style I’ve managed to impersonate by performing such draconian surgery. Today, I’m editing a film called Intimacy [n.d.]. I think it will be one minute and forty-seven seconds long. Its star is a photographer named Maxwell Harvey-Sampson, who is lying on a bed. He stares at me, or at the camera, for a long time. I think he knows I’m enjoying the light falling on his face; I think he knows I’m admiring how long he can gaze at me without blinking. The film’s methodology is screen test, but, in truth, there’s no test and no screen, just staring, mutual acceptance, stillness – the sensual and slightly soporific state of waiting for the voiceover to arrive.

Tell me when you think we’re “done.” Maybe one concluding cadenza from you, then one more from me? Two quickies, codas?

As a beloved teacher of mine once asked me, rhetorically, “How quietly can you play that passage?” I’m still asking myself that question

TL: Of course, now that this conversation is coming to an end, I have a million more questions to ask you. Like: Did you know that “badinage” comes from the Provencal word for to gape, which is surely one of the coziest parts of the Q&A as genre? Or: Do you think that different styles ever speak to one another like specimens in a natural history museum display, after dark, when the visitors have all been shooed away? Or are they like marmalade, suspended and without temporal ambiguity?

I am not over “secret matteness” as an image: you who give image to what I once imagined was ineffable concept. So, one final question, tenor to alto, which is a question about infinitude: What did you put in your first bureau drawers? I don’t want to deny you your regret or insist on some childhood origin story (a first!). From the outside, it seems you’ve found an abundant way of taking the stacks of shelving units (a transliterated dispositif) wherever you go. And, on behalf of what that kind of space makes with others – for self-elaboration, for trying things on, for repetition – thank you.

This is my concluding credenza. Imagine trying to break up with me!

Still from Wayne Koestenbaum, The Ex-Lovers, 2023, 11 min.

WK: In my bureau drawers, then, now, no contraband, no drama; but in my desk drawer, long ago, I kept a miniature Torah, ripped and flimsy, a scroll that to me had scant significance, though I knew it could not be thrown away. Also in that drawer: photos of Vanessa Redgrave and Sophia Loren. Glue, too, Elmer’s, and glitter, and index cards, on which I’d composed plaints in the style of Carole King or Joni Mitchell. My mother was the master of my desk drawer; she had the power to inspect it, empty it, disdain it, or leave it alone. I like saying “the maternal function” (thus I turn emotions into algebra); the maternal function was desk-drawer knowledge, desk-drawer supervision, desk-drawer despoiling.

Last night, I dreamt that I played a passage from [Robert] Schumann in a master class, and the illustrious pedagogue said, “Notice his touch.” I’d failed to render the passage with finesse, but the master found something marginally memorable in my touch. I think he noticed my touch’s remoteness – a certain distance (call it acculturation to cruelty?) that my fingers maintained toward the keys, so that, even as I was depressing the keys with curved fingertips, I was also anesthetizing the keys, muting them, holding them at bay. Toward the keys, I was behaving with a digital equivalent of psychoanalytic listening: a floating attentiveness containing a soupçon of indifference. But, to achieve that relation to the keys, I needed to tighten my body, deprive it of its natural portion of elasticity. Make the body non-nimble, in order to attain laudable “touch.” Through such self-abnegating internal contortions, one can achieve what I sometimes call a “diminuendo-unto-nothing.” The phrase in question doesn’t end; it disappears. As a beloved teacher of mine once asked me, rhetorically, “How quietly can you play that passage?” I’m still asking myself that question, even if, through verbal distension and elongation, I’m committing here the opposite of quietness.

TL: I recently learned that some of the earliest libraries (in Europe) were made using desk drawers as their model for scale, made to measure using the size of the total number of books imagined necessary to encompass the totality of human knowledge, divided by the size of each title. After hearing that, I feel especially fortunate for your Elmer’s, your glitter, and especially your index cards, which, in and despite their familial origins, seem to also offer the ongoing promise of a despoiling enjoyed by several more than one.

What you wrote to me of the psychoanalyst’s listening practice has really stayed with me ... Why won’t he just get with me on the couch already!? Yes, I guess the tightening of the body can unexpectedly lead toward diminuendo. But I so prefer your Schumann method: the way that, sometimes, we can find our way out of the traps of genre – be it the marriage plot or the return home – via the chute of a well-placed dream.

Shall we continue this offline, perhaps as a dream book à deux, ready to morph and find new legs with which to crawl? Text me! But please let’s start with a fresh scoop of ice cream.

___