As Western politics auto-destructs into a meme, grasping at attention like an upset toddler, the London art world continues to ignore it with quiet, maternal dedication. Will this weekend be any different? London’s younger galleries are fostering the work of a new generation to various degrees of novelty. Many participated in last year’s Frieze Spotlight – an event that felt like an ordinance for a scene that functions, for all its newness, with the semblance of what came before. I hoped the model of Condo – an art fair organized by Carlos/Ishikawa director Vanessa Carlos, in which small and mid-size local galleries host yet smaller galleries from abroad – could inspire a shift. Between reading Vladimir Nabokov’s Despair (1934), watching hyperspeed TikToks and tasteful, Lynchian AI edits on the purposely more fucked for-you-page of my private account, I walk between shows, searching for the three kinds of art I usually like: the macabre; musings on innocence; and quotations from the domestic. Five stars to any show that has all three.

At Auto Italia on Thursday night for Alex Margo Arden’s solo “Safety Curtain.” A show that looks at acts of vandalism against art across history – featuring exact reproductions of artworks after they’ve been targeted by protestors. These paintings felt mass-produced. Not in a bad way. Reading critic Hatty Nestor’s response, my suspicions were confirmed by a singular, innocuous line: “[the replicas] are handed over to a reproduction studio who create hand-painted reproductions …” Van Gogh’s Sunflowers and Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa are venerated images that have already been cheapened beyond recognition through mass reproduction. You can acquire masterpieces via an Etsy drop-shipping page if you want. Shiny art-world globalism leads to dusty museum conservation in the next room, where Backstage Campaign (2025) features old, beaten-up art handling crates displayed in diminishing sizes. Once containing casts from the Royal Academy’s renowned collection, they now contain the remnant mechanisms of a historical institution; antique display objects, brooms, and, in the furthest crate, facing into a corner, a worker’s discarded sandwich. I slipped on artist Jenkin Van Zyl’s devil tail and nearly fell into one. Art is best when it’s disguised as theatre.

View of “Safety Curtain,” Auto Italia, London, 2025. Courtesy: the artist and Auto Italia. Photos: Jack Elliot Edwards

Next, Rose Easton opens “White Knuckle” with the work of twenty-two-year-old Tasneem Sarkez. The crowd is shorter than Auto Italia’s (which was filled with Royal Academy graduates – probably just younger). The artist’s just been back to Libya for the first time since before the 2011 Civil War. We talk the high camp of Gaddafi and Americana – her painting The Real Superhero Key (2024) is named after an eagle-printed find from a Chinatown hardware store. “It’s an oxymoron – because, you know, they’re imaginary superheroes. Putting ‘real’ is unnecessarily affirmative.”

Outside, there’s not even a murmur about Dean Kissick or his article “The Painted Protest” – because everyone here is under twenty-five and has already resigned themselves to his truths in art school. Had people brought it up, you can imagine loud sighs and bristling – an anticipation of delivering a pre-prepared speech. The night ends with a gallery dinner at Sông Quê, where no one talks about art, but someone tells me about manga artist Junji Itō and autism-masking in young women – a different kind of art.

View of “White-Knuckle,” Rose Easton, London

Tasneem Sarkez, The Real Superhero Key, 2024, oil on canvas, 22.9 x 53.3 cm

Saturday morning. I’m with self-proclaimed internet genius and real-life genius Taylor Richardson (of recent triple-platinum internet fame for a video of him dancing to “F U 2x” by rapper Lil Baby). Usually, art should be viewed in a mire of solipsism. Today, it feels important to be accompanied by a mind with superior internet connoisseurship. “I’m the most on the internet of anyone,” says Taylor. He makes me a deep-fried edit of the day, which soothes my brain like clonazepam. See below.

We start at Project Native Informant. (I’m unsure what’s going on with PNI; they appear to have lost all their staff and the representation of artist Joseph Yaeger.) In Phung-Tien Phan’s show “doesn’t work,” the video dog (2025) shows a toy version of Tintin’s terrier Snowy, followed across Phan’s family home with an iPhone. The dog notices and attacks the camera, childlike animism and awkward angles forming a relief from overstimulating web-editing. In Volkswagen (Romeo and Juliet) (2025), a multi-layered sculptural work, a miniature dollhouse is constructed within a shelf. Above, Phan has made a home altar to Japanese filmmaker and actor Takeshi Kitano. At the pinnacle, a disused coffee machine contains flowers - one of which supports a hanging image from Gregg Araki’s film Doom Generation (1995). Phan presents her love of violent romanticism with the spirit of playtime. I’m a sucker for Yakuza films and the miniaturization of domestic space.

View of “doesn’t work,” Project Native Informant, London, 2025. Both courtesy: the artist and Project Native Informant, London

Phung-Tien Phan, Volkswagen (Romeo and Juliet), 2025. wood, glass, Perspex, found coffee machine, artists clothing, photograph, marble, acrylic, dolls house furniture, incense sticks, found branch, ribbon, live flowers and light, 186 x 82 x 48 cm

Next door, mother’s tankstation is showing Erin M. Riley in a collaborative presentation with P.P.O.W., New York. Taylor calls the weft-faced tapestry work Webcam Control (2024) “the sickest thing he’s ever seen,” only to reiterate later that “he’s seen so many fucking tapestry works.” In First Light (2023), collaged images sit on a Grand Theft Auto-esque landscape alongside pop-up windows that read “how to get child support” and “affidavit.” They crowd the picture plane like desktop viruses – a truncated, tattooed torso strides across the landscape wearing pants that say “daddy issues.” If being online has taught me how to look at images and form instantaneous categories of “cringe” or “sick,” then looking at art in real life has taught me that I’m narrow-minded, judgemental, and too easily bored.

View of “Look Back At It,” mother’s tankstation, London, 2025. Courtesy: the artist; mother’s tankstation, Dublin / London; P·P·O·W, New York

“The Condo bus is leaving without us,” says Taylor, pointing out a big unmarked car that well-to-do-looking people are being loaded onto outside PNI. A sweet-sixteen limousine for people in camel wrap coats who don’t know how to get to Bethnal Green on public transport. We visit Maureen Paley, hosting Air de Paris, which has conceived a show of musings on xerography as a medium. Prints by Pati Hill hang opposite a singular, self-referential image by Wolfgang Tillmans of a photocopier in his studio: CLC 800, dismantled, a (2011). In Hill’s Untitled (white gloves) (1976), the flattening of the copier approximates the phantasmagoria of early silver gelatin prints, recalling an image I obsess over: a woman’s lone glove in André Breton’s novel Nadja (1928).

Works by Patti Hill. Installation views, Studio M, London. Courtesy: Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans, CLC 800, dismantled, a, 2011. Photo: Stephen James

At Brunette Coleman, hosting New York’s Francis Irv, a friend tells me London is having a moment of “patina minimalism” as we look at new works by Rachel Fäth. Locker 5 and Locker 6 (both 2024) are shaped by the constraining spaces of storage lockers in a “community workspace.” At this juncture, I’ve lost all analytical processes. Fäth’s use of densely packed scrap metal mostly just reminds me of Pixar’s robo-romcom WALL-E (2008).

View of Condo 2025, Brunette Coleman, London, with (left to right) Rachel Fäth, Locker 6, 2024; Zazou Roddam, Desert Rose, 2024–25; and Rachel Fäth, Locker 5, 2024. Courtesy: the artists; Brunette Coleman, London; and Francis Irv, New York

Because we could not figure out what shows were “in” Condo (because we were not on the Condo Bus), we saw Matthias Groebel’s “Skull Fuck” at Modern Art. Taylor admires the white cube space, advising that Stuart Shave should “Get a set of speakers and a turntable and then do a Boiler Room” and that “Skrillex should play.” I think how good the DJ would look against one of the exhibition’s paintings, flat canvases with paint applied by a machine to create low-resolution pointillist stills taken from the early days of the 24-hour news cycle.

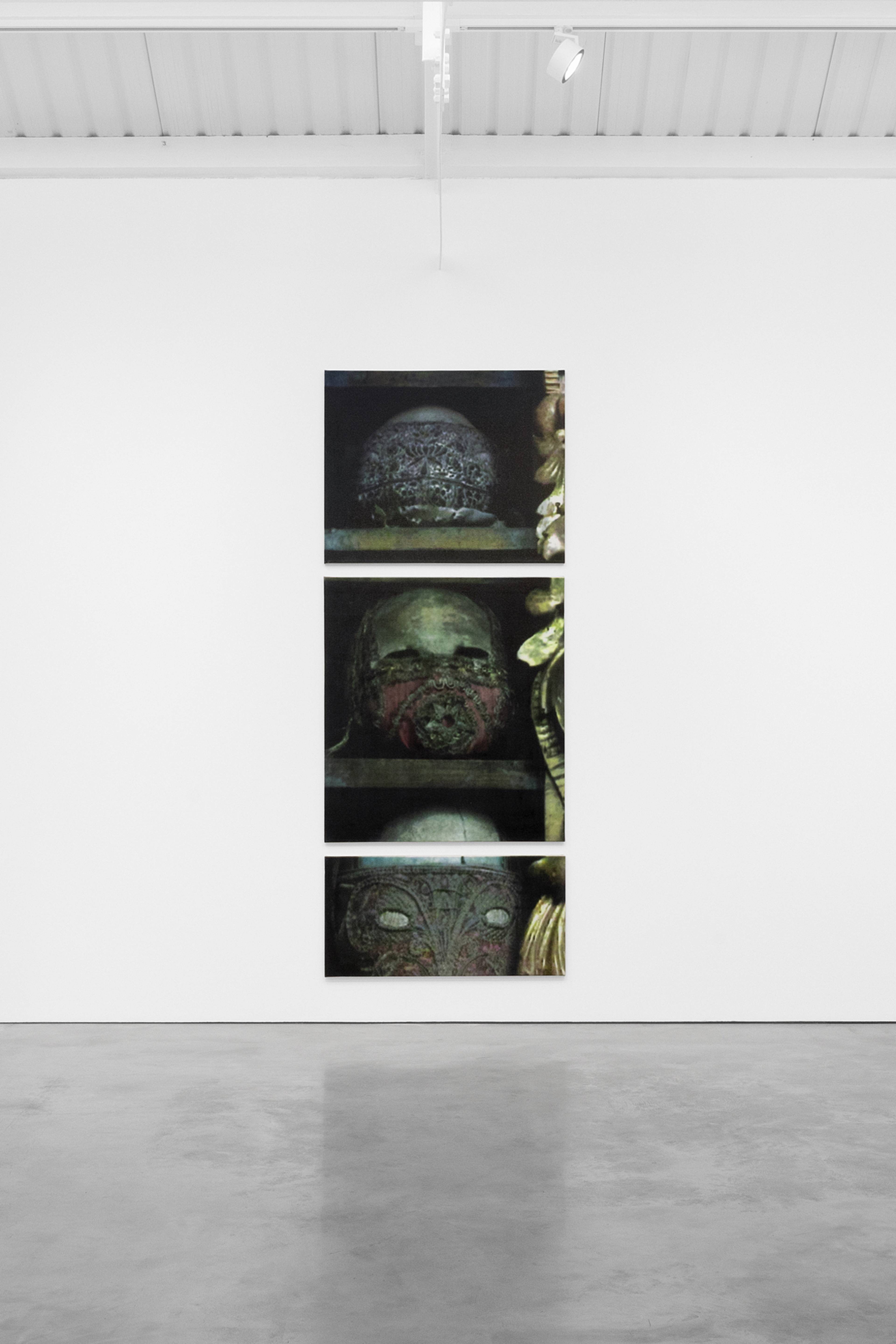

Virgins (2002–03) is a zoomed-in clipping of one of Groebel’s photographs of skulls with rococo masks. Oneirically entertaining, affecting but disturbing, the pieces recall Gregor Schneider’s invitation for visitors to the 49th Venice Biennale to experience the twenty-year alteration of his family home in Dead Haus u r (2001, German Pavilion). If Groebel’s decontextualized image seems to forerun Issy Wood's work, his use of DIY machines to paint seems to shield him from the epithet of zombie figuration. Groebel, I read in the press release, “doesn’t believe in the concept of content.”

Matthias Groebel, Virgins, 2002–03, acrylic on canvas 250 x 100 cm. © Matthias Groebel. Courtesy: the artist and Modern Art, London

Later that night, Condo parties in a private members’ club. The kind that has a parlor hang and Modigliani reproductions. My friend Clyde, another journalist from New York, tells me that the party has “more hot young people than in NYC” – but I mishear him over the noise and say, “I know, right! I don’t know who anyone is, and they are all way older.” He later texts me, “NYC would be 4% hot and cool; this room was a solid 30%.” In fact, the old person I wanted to talk to was Groebel. Seeing him repeatedly walking around alone in a thinly checked button-down, it was hard to place him as the author of “Skull Fuck.” A staff member tells us the name came from a 1971 live album by The Grateful Dead.

The party is boring – although no parties are immediately fun. Most of the partygoers are segregated by age into one room that includes friends who work at galleries (curator and artist Blue Marcus, photographer Alex Arauz, performance artist Jaya Twill) and artists with works in Condo like Sarkez and Areena Ang. Things become incrementally messier as a weed vape is passed around. You can always tell who runs galleries because their emerging-designer clothes don’t fit their twelve-thousand-pound-a-year tax declaration. The relationship between talent and their producers at an art-world party smells like control and Dover Street Market stores. When I leave at 1am, the queue outside is very long.

A private member’s club in London

Left to right: Blue Marcus, Lydia Eliza Traill, and Tasneem Sarkez

Sunday morning. Arcadia Missa is hosting not one but three (!) galleries: Florence’s Veda, as well as 243 Luz and Roland Ross, both from Margate. Playthings and naiveté in art usually get my phone out to take a picture. 243 Luz presents Ang’s pencil drawings, “Marionette Studies,” which depict an afflicted Pinocchio, the puppet face down and ass up – a “real boy” reframed. “I believe Collodi’s (1882) original tale is one of gender” the artist tells me. In one drawing, Pinocchio stands face-to-face with the artist’s self-portrait – the toy’s malleability a ready allegory of the indeterminate body and failed becomings. A paper collage by James Whittingham, of doll faces across three sheets of A4, was also delightful.

Areena Ang, three works from “The Marionette,” 2025. Installation views, Arcadia Missa, London, 2025. Courtesy: the artists; Arcadia Missa, London; Roland Ross, Margate; and 243 Luz, Margate; Photos: Tom Carter

James Whittingham, Onlookers (boy in a bow tie), 2024, graphite, PVA glue, tissue paper, cut paper clips, feathers, dimensions variable

At Sadie Coles, hosting Jahmek Contemporary from Luanda, Angola, I think how often domesticity appears in contemporary installation work – Dorothea Tanning’s Room 202 (1970–72), Robert Gober’s 2015 retrospective at MoMA, etc. Back in the present, Sandra Poulson’s makes tableaux of found objects and Dutch domestic furniture: a bed, a chest of drawers, a swing, and a toilet, all constructed in the vernacular of Luandan building techniques. Poulson describes her father chastising her childhood messes – “This bedroom looks like a republic!” – as a starting point for her work. Objects are perverted with slogans taken from t-shirts distributed for free by political groups; an EU logo appears on the headstand of a broken bedframe.

View of Sandra Poulson, Sadie Coles, London, 2025. Courtesy: the artist and Jahmek Contemporary Art, Luanda. Photo: Dami Vaughan

Speaking of disrupted domesticities: Later that evening, I visit the inaugural opening of apartment gallery/no space Chicago. held in the hallway of a severely neglected rental building that has been passed through arty twenty-somethings for years. Named after the 1990s apartment galleries of the post-1987 financial crash, the exhibition appealed to me with its title, “quarter-life crisis” (I was born in 2000). A cheaply framed photograph of a stack of Thomas Bernhard books is like an intellectual-starter-pack meme: Try to figure out what kind of girl you are through a photograph of Jean Rhys’s Good Morning Midnight (1939), Georges Bataille's Eroticism (1957), and Michel Houellebecq’s Atomised (1998), collaged next to some ribbon and a cigarette. The work is titled Hatred and Affection (2024) – a pretentious but acerbic depiction of turning twenty-five.

My weekend ends on a high note in the Chicago bathroom. I realise the door’s broken glass window, crudely repaired with cardboard, is not an install – but had been kicked down by my boyfriend over a year ago. The lock is now stuffed with tissue.

Gorin Arif, Hatred and Affection, 2024. Installation view, Chicago, London, 2025

Bathroom door at Chicago, London, 2025. Photos: the Lydia Eliza Traill

___

cOnDo LoNdOn 2025

Various galleries, mostly North London

18 Jan – 15 Feb 2025