DAY ONE

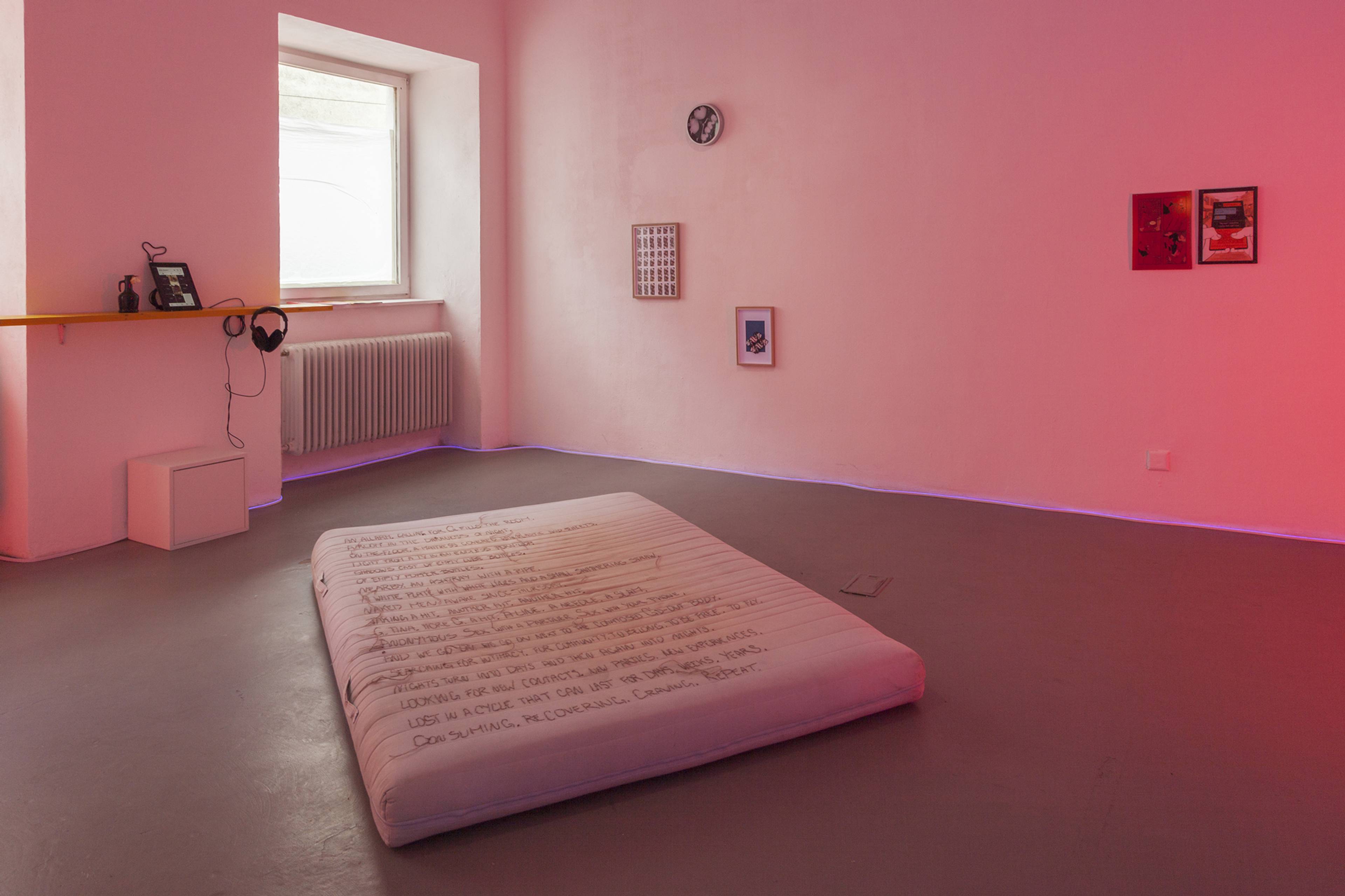

My fifty-nine hours in Vienna starts with chemsex. Embroidered, projected, written on baking paper in Farsi. The group exhibition “Beyond the High. The Chemsex Experience: Crisis, Resilience and Community” at ENTRE is my first stop during Independent Space Index, an annual festival for the city’s offspaces. The mattress on the floor and the soft, red light make the gallery both a den and a sanctuary, like a physical translation of the “tremendous gap between our politics and the material realities of our sexual relations,” to quote poet Ariana Reines in Wave of Blood (2024). We want to be both worshiped and degraded, but we don’t have the language to express it. Here, the artists try and find these words.

I keep looking at a clock on the wall, an element of Chemsex Dialogues (2024) by Sascha Knorr. It’s been customized with a repeating, low-angle shot of one man penetrating another, mind-numbingly deeply. The numbers have been replaced with the letter G. The idea is simple – the euphorigenic and sedative GHB as totalizing system – but there is something about the flattening of self-obliteration into domestic object that compellingly disturbs.

View of “Beyond the High. The Chemsex Experience: Crisis, Resilience and Community,” ENTRE, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

I ask B, another writer, if this show is a good or bad omen. We’re not sure. The festival literally indexes the sixty-plus “offspaces” across Vienna, run out of galleries, studios, apartments, bars, car boots, phone booths. It’s a network of outsider-insiders and insider-outsiders, where the claim to what art is and does is tightly smiling conflict. I’m going to try and open its mouth.

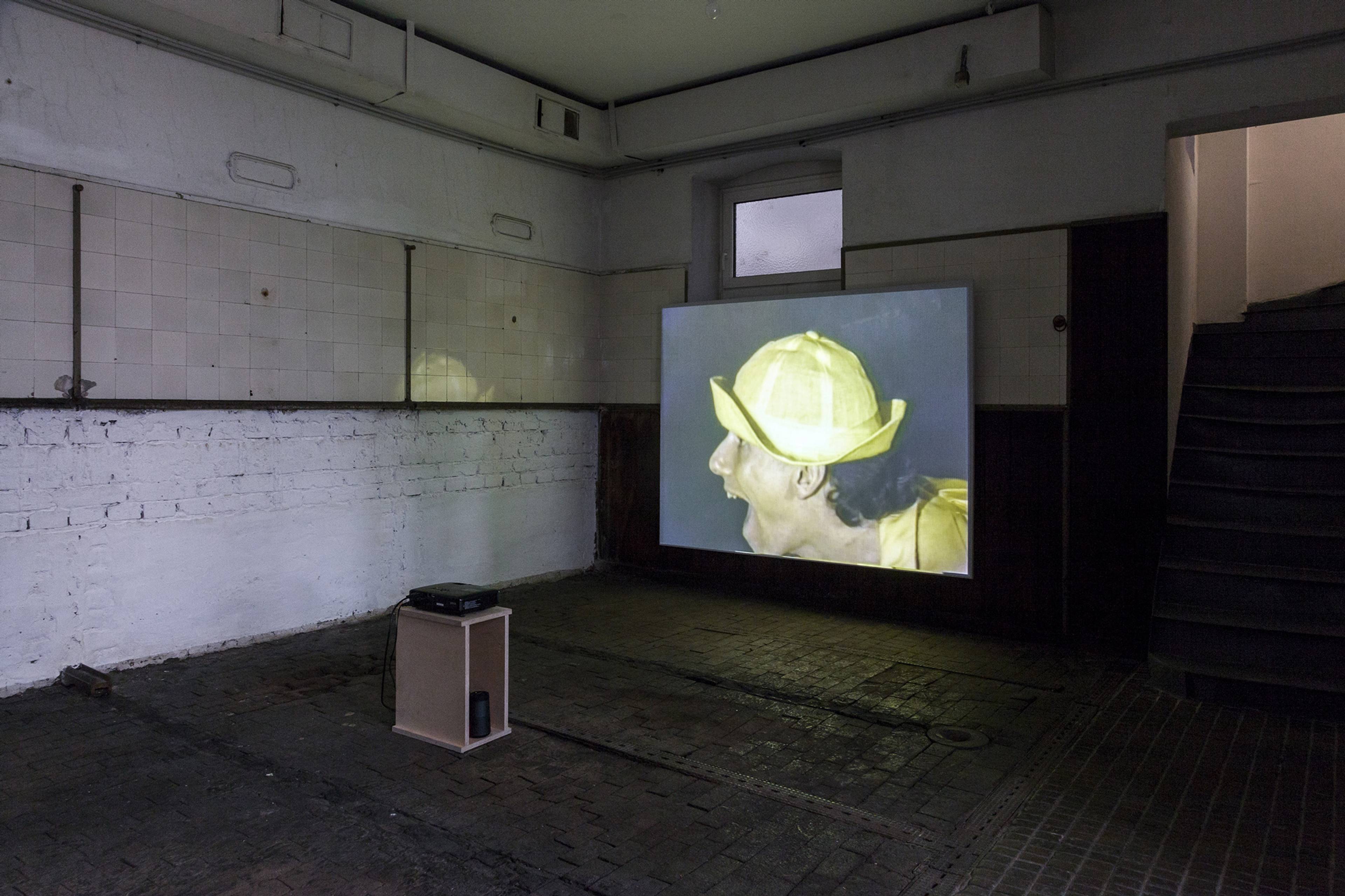

I knew this already, but still: I don’t like hearing curators speak. Particularly when they don’t want to. Can curators be punks? This energy is at least felt in the duo show at Laurenz, a former stable, where Mike Kelley’s first video performance, The Banana Man (1983), is projected in the downstairs gallery. The speakers are bad and the equine smell lingers, wafting up to a sparse upstairs room where two sculptures by Marlie Mul blink back at me. Coiled silicone sheets cinched by metal clasps the size of a small, flat head. Sometimes adorned with streaky hair. Wall jewelry or pointless punctuation. The tension is interesting, between Kelley’s childishly recycled, vaudeville masculinity and industrial spirals of fetishized nothing. Critically flaccid, a uselessness to think through.

Mike Kelley, The Banana Man, 1983. Installation view, Laurenz, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

The rest of the evening passes in openings. A close-up of a bird’s eye rendered in graphite. A performance made with flashing bike lights. A drummer says “wave” in French and then imitates one for what seems like eternity. I end the night at new jörg, among walls of dusty paintings by David Gruber. Oh, dusty paintings. All color cut with gray. Its 21st-century Baudelaire, but now, we’re melancholic for the grime.

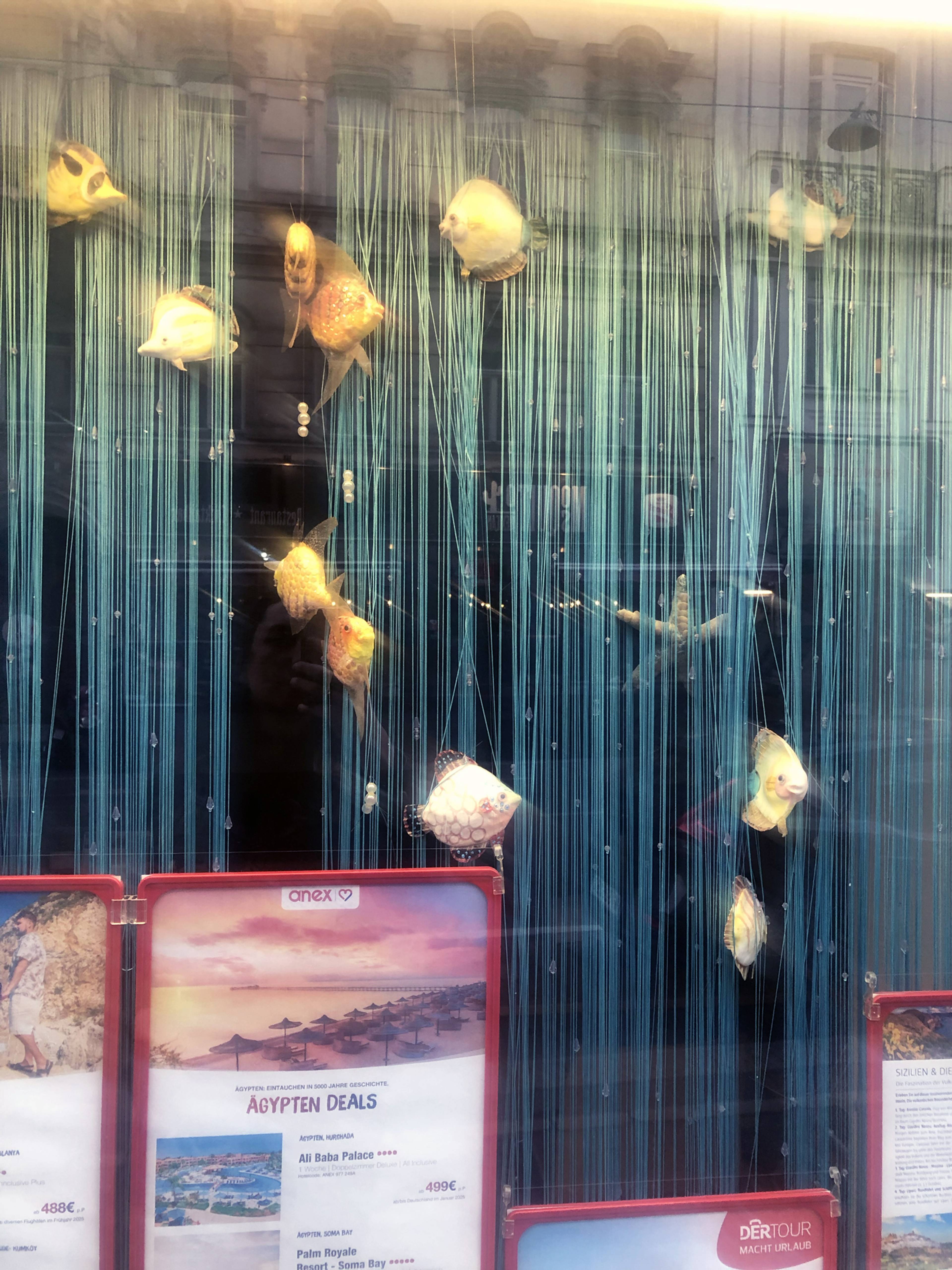

On the way home, I think that, if I’m honest with myself, what moved me most was a travel agency’s window display, of plastic fish suspended in a bright-blue string curtain. Offspaces really do abound here, it turns out – even in the city’s street-facing vitrines.

View of David Gruber, “Persona,” new jörg, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

DAY TWO

Hotel breakfast with B and T, another touring writer. We talk the red and white in Zuza Golińska’s sculptures at WAF. Is this (ironic) nationalist sculpture? To make her work, the artist collaborates closely with the metal workers, going from factory to factory. T tells us that this kind of metal sculpture has a certain history in Poland, citing Iza Tarasewicz and Monika Sosnowska. Slow theaters of post-Communist dissolution, they remind me of Aria Dean’s view of Robert Morris as the last American artist, before everything dissolved into the floating signifiers of globalization. But what about the other side of the Iron Curtain? Can (ironic) nationalism be a critical form?

View of Zuza Golińska x Cezary Poniatowski, “Remnants of the Current,” WAF, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

We walk through TU Wien, Vienna’s University of Technology. Screaming with graffiti against the ongoing genocide in Palestine, it feels like the campus could be an offspace too.

The white cube reappears a few blocks further along. At Pech, Nicolas Jasmin shows a very short, looped video of a butterfly fluttering over Klaus Kinski’s face, hidden behind a sunset-red partition. It’s called Insecte (2000), but we’re meant to think inceste. The exhibition text reminds us how this once revered actor abused his eldest daughter, Pola, who published a revelatory memoir in 2013. The text also suggests Jasmin’s video is about the butterfly. I think the video is about metaphor and metonymy: The butterfly is ephemeral transformation; Klaus Kinski stands in for libidinal destruction. The video flickers between the “real thing” and their doubles, undoing the sticky associations that prevent any possible transformation taking place. Can the insect rebirth Kinski? Can art (or the critic) indulge this kind of whimsy?

We move to another bar and talk about throuples and artists that are both horrible and insane.

I suddenly need to lie down. I go to school. It’s a discursive performance space. The floor is lavender, the air is burnt sage, the cushions are scattered. Someone with a visibly radiant spirit is mixing vinyls. They’re wearing a t-shirt with “HILDEGARD” on the front, “VON BINGEN” on the back. Midori Takada, Fatima Al Qadiri, and Moor Mother are also here, as sounds/spirits. Utopia is Alice Coltrane’s voice. I stay until after the chanting crescendo.

I find prolet.AIR on one of the last floors of an apartment building. A queer feminist shared studio with a gallery space, they throw watercolor parties and have a windowsill of plants belonging to their various exes. Mainly succulents. I spend some time with pencil drawings by Wania Leila Castronovo. It seems the artist was trying to invent their subject matter as they were drawing, recording the tenuous link between phenomena and brains. Different cerebral “chemistry” or “wiring” and the world would look completely different. Maybe drawing can give us another brain, too?

View of Nicolas Jasmin, “L’Insecte,” Pech, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

View of “SOUND AND SILENCE,” school, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

When I get to Prosopopoeia, an art/writing space in a social housing complex, I want to renovate my brain with Lisa Robertson’s Proverbs of a She-Dandy (2018) and Anne Schmidt’s Me after two anal orgasms (2023), both sitting on the bookshelf. The rest of the space is populated by Ethan Assouline’s collaged books and tiny doors. His show, “Tout va bien,” fucks with the artifacts of pre-fabricated desire, staining and screwing heavy symbols: children’s bedheads, broken clocks, Sex and the City (1998–2004) memorabilia. The work reminds me of Anne Bourse’s fictional books, though treated with the formal insolence of Henrik Olesen and Manfred Pernice. A room of sexy gloom.

I miss the Loggia opening to have spinach knödel with B and T in a café next to a paint-stained statue of an antisemitic former mayor, Karl Lueger. An inspiration to Hitler, his bronze is now a monument to shame. Piano music tinkles at the bar. Eine kliene, etc … D joins. We talk about whether “Diamonds” is a good title for a novel. Should writers lean into or away from Rihanna? We move to another bar and talk about throuples and artists that are both horrible and insane. We also play other games, providing the following conclusions: Virginia Woolf is a boy. Kafka is a girl. Angela Merkel is an orthopedic shoe. Zendaya is a two-day flu.

View of “see the image above,” prolet.AIR, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Janine Schranz

View of Ethan Assouline, “tout va bien,” Prosopopoeia, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

DAY THREE

I go to a talk interesting for its silence. In Freud’s hometown, of course the offspace scene has an unconscious. The panelists, representing their respective spaces, talk about funding and freedom, about how the institution makes political work decorative. No one says too much; we all know these things are more honest as gossip.

I then get lost in a pink carpark, two floors under the opera house. There are many dark and chunky Volkswagens, yet only one spilling white fluorescent light – VAN. Inside is a melted Perspex saddle called I ride (Tesla 1499721-00-A) (2025). Liquidated by Elon? Nanna Kaiser’s exhibition reminds me of The Besieged City (1949) by Clarice Lispector, set in provincial Brazil in the 1920s. The increasing presence of horses signals coming industrialization. Where are they now? Musk zaps the world into data, we look at melted saddles in car boots.

On foot, I see at least two more unofficial offspaces, the first being a café with a munted doll out the front. Through a hole in its skin, you can see that its bones are brown. Further down the street, there is an old LG air-conditioning ad with a polar bear saying ,,Life’s Good.”

Window display, Vienna

Munted doll

,,Life’s Good.” Photos: the author

Australian artists Jasper Jorden-Lang and Alexandra Ragg have a duo show, “The Devil’s Mill,” at PILOT. Hard to put anything in this room because of the octagonal dark wood ceiling. It’s like all of Austrian history has lured you in, just to crush you underneath. Ragg’s paintings are smoky, Jorden-Lang’s cut and drain. The combination is sparse and rhythmic: fetid-clean, fetid-clean. The monochromes take me back to Melbourne. There is an underlying conversation going on about settler Australia’s relationship to flat color: the sparse Fred Williams, John Nixon, Spencer Lai, Lucina Lane, Helen Johnson’s flare painting. How do you work with the catastrophic lie of the flat void, the terra nullius upon which a colony was built? These paintings efface all form of horizon or perspective, an emptiness that feels interesting when displaced within in the heart of (another) old, dying empire.

I finally make it to Loggia, for “No Partial” by Len Schweder. The works seem to do something productive with the contemporary mistrust and compulsion towards painting. This is probably because they are not paintings, but oil pastels: soft, blurred, and technically very peculiar. The subject matters seem simple: landscapes, sunbursts, water, trees, but all filtered through an idiosyncratic logic of reduction, as though the artist were playing around with a disappearing world. There is something both hazy and mechanical to their making, like a computer on barbiturates teaching us how to properly look at a sunset. I felt the same sweet anxiety when looking at Ull Hohn’s work. Though now it’s less of a game; now, the game seems over.

View of Jasper Jordan-Lang & Alexandra Ragg, “Devil’s Mill,” Pilot, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Janine Schranz

View of Len Schweder, “No Partial,” Loggia, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

I then fly by hoast (“Waiting for a larger sun”), where the world really is over. A group of Hungarian artists imagine that they are living on another planet, drinking martinis in flames (Anna Hoòz’s sculpture Tresolith, 2025). At arka arka (“Light bent backwards, waiting to be forgotten”), it gets a bit heretical. There are orificed wings, an open-mouthed Janus, and stripped-back, sacred geometries. I move on to a newish industrial area out east, and get lost until I find a charming person reading Michel Houellebecq. At Can, Nina Zeljović presents Calendar, a site-specific painting installation. The artist has cut up time in the form of a meters-long laminated wooden oval, used as a support for abstract paintings. They feel both slacker and reverential (of Marc Rothko, Philip Guston, Amy Sillman … Michaela Eichwald?). There’s an interesting contradiction to this trio of shows, a humble audaciousness. Refuse the big “system” – the Earth, religion, time – only to make its void sensual, livable again.

It’s 7pm and I’ve run out of time. I walk to the train station and see graffiti from faraway. I don’t have time to actually look, but between the buildings, I can read: “world” and “hysteria.” I imagine the earth’s womb circulating freely in its body, as this “illness” was once diagnosed. Is this what I’ve been trying to find? Is this what Freud would say an offspace really is? GHB clocks, newly drawn brains, stoned computers. Yes, I think so.

Exterior view of Can, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

Nina Zeljković, Calendar, 2025. Installation view, Can, Vienna, 2025. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

___

Independent Space Index 2025

Various venues, Vienna

30 May – 1 June 2025