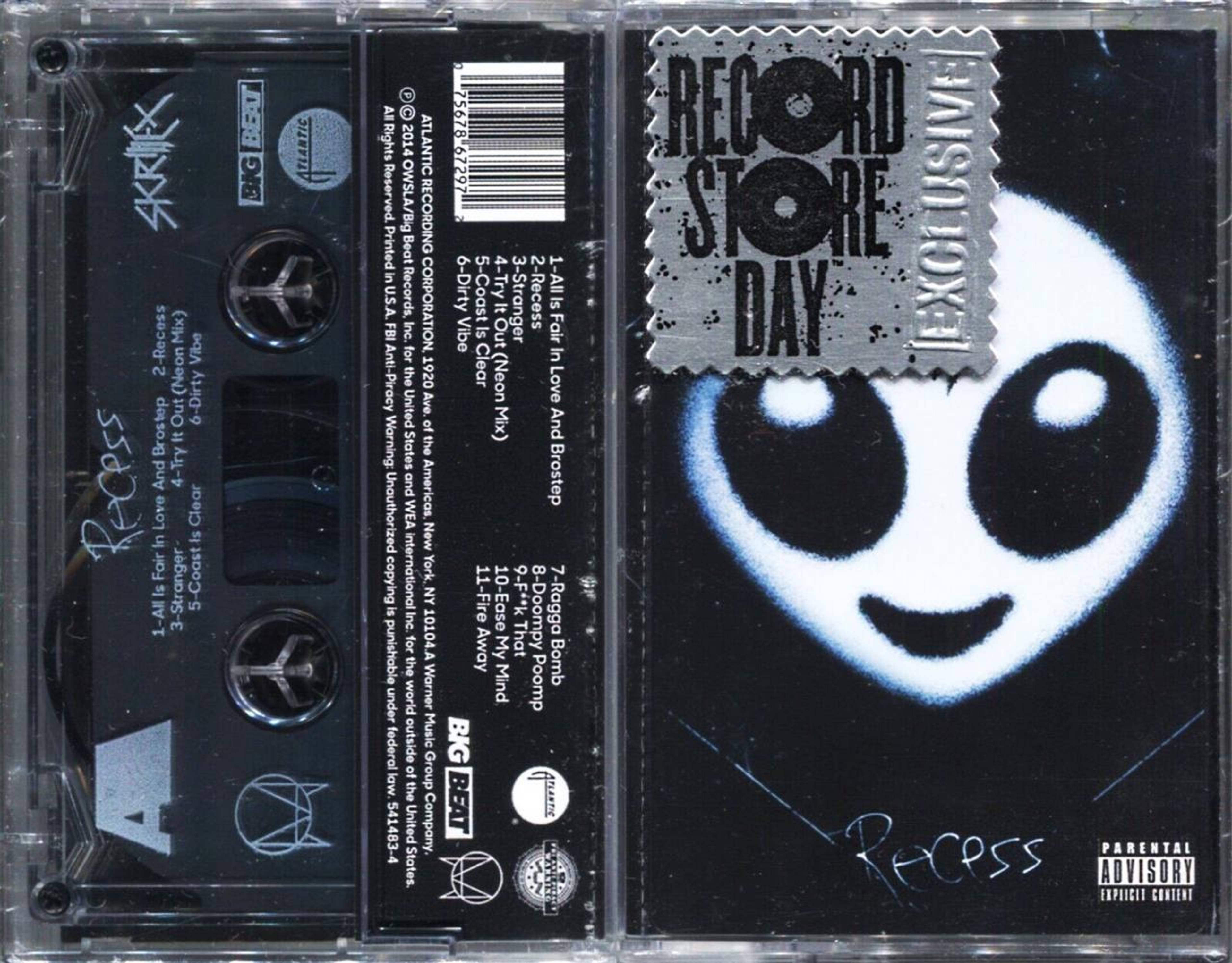

Record Store Day, 2014: As a joke, I buy a limited-edition copy of Skrillex’s album Recess (2014) on cassette. My car only played tapes at the time, which meant my rotation was confined to classic rock handed down by my parents and lo-fi indie pop bootlegged by friends. Skrillex was music that would offend both parties equally. Played between James Taylor and Car Seat Headrest, its shrill and acerbic bass drops grew on me like a fungus. It was mindless. It went hard. I thought it was the stupidest music I had ever heard. I started speeding down highways with previously unknown abandon, experiencing a taste of real freedom for perhaps the first time in my life. A precocious little luddite who took myself too seriously at sixteen, I had unwittingly participated in one of my generation’s great coming-of-age experiences: By entering the matrix of performative irony, I had bought into something that would change me forever.

New Year’s Eve, 2022: I’m dancing in a strangely furnished warehouse in East Williamsburg, at an event hosted by the Brooklyn nightclub Rash, the final minutes of the old year elapsing to the sound of…Skrillex. Is this really how we enter the future? I wondered, bobbing my head to a dub riff that evoked both a passing jet and a heart defibrillator. Some of this shit I hadn’t heard in almost a decade, though it didn’t sound old. It still projected the same emotions as when I’d first played it on the open highways of my youth: an impish disregard for taste matched by an almost lobotomized sense of pleasure and prescient sensory overload.

Skrillex, Recess, 2014, cassette, recto-verso

It was everything except the music that had changed. The world that once incorporated CDs and cassettes – discrete pieces of information that could only be accessed when slotted into the right portals – has disappeared, eaten from the inside by the ever-present web. Music that once sounded tauntingly futuristic, like getting trapped in the Death Star’s trash compactor, increasingly animated the experience of everyday life. Instead of whatever stoner-creep-frat contingent that had once defined Skrillex’s early output as “brostep,” the crowd at Rash was queer, diverse, and self-consciously alt, with hand-knitted hats and buttons pinned to bondage harnesses. They reminded me of the kids I’d hung out with in my hometown’s DIY scene – people who used Modest Mouse lyrics for Tumblr URLs and reveled in being misunderstood. Had this crowd really followed me along the same trajectory, from self-important angst to smooth-brained ebullience? How did we all end up here, listening to hyperpop on the precipice of a new landmark in time?

Of course, “hyperpop” is just a word made up by Spotify to better sell songs. At a birthday party I attended the night after the show on New Year’s, a girl who works at Harper’s explained to me that the real hyperpop experience died before the pandemic began, and credited its short lifespan to two 100 gecs DJ sets from the fall of 2019, one of which was an NYU student event. “It wasn’t even called hyperpop back then,” she tells me over the kitchen island’s baguette-candelabra. “We just called it Charli XCX-adjacent.” What ruined the movement, in her opinion, was its newfound self-awareness. “We just went to those shows because we followed PC Music,” she said, referring to the XCX producers in question. “Now you see the crowd at Heaven or wherever and it’s clear they’re all thinking: I’m here to listen to ‘hyperpop’ right now.”

One of my favorite parts of the night at any show is the dilation of this moment – the point where the DJs fuck with the sample so much that you question whether or not something has broken.

Dead or alive, it’s been around for a while. Pitchfork published a 2014 feature on the label PC Music, thereby corrupting the circle of influence from true believers to the kind of sickos that read articles to learn about music. Maybe this was what had so affected me at Rash, realizing the sound of the “new thing” was no longer that new, just as it and everything else was on the cusp of turning a year older. In its early days, hyperpop was treated as an object of suspicion, and many people thought its cut-copy lyrics and canned vocals were a kind of trolling. As it turns out, you can’t stave off sincerity forever, especially when increased attention reinforces a certain baseline of commitment. The version of the (ostensibly passé) hyperpop scene that I’ve experienced in the past year-and-a-half comes off instead as unapologetically earnest, striving to be candid rather than hiding behind a sleek pop persona or inscrutable mischief.

On the decks at the Rash show was Fourtnite Battlepass, an informal DJ collective also known as the Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeahs. The formation is nominally led by umru, the PC Music signee and Charli XCX producer. While he can sell out a small venue alone, he prefers playing with friends and has a habit of booking shows as one component of a b2b2b2b, sharing the decks with other musicians that often include the self-produced artist underscores, the scene’s erstwhile fashion designer Elena Fortune, and umru’s childhood best friend, Tiam Schaper. In front of the decks, people bounced up and down like coked-out kangaroos, though certain tracks elicited an impromptu mosh pit. Bunny-eared beanies flopped to communal gyrations. Everyone seemed to have a phone or a camcorder in hand, and the performers were no exception.

Fourtnight Battlepass perform at Rash NYE, New York, 2023

When I first started going to see house and techno DJ sets, around 2016, I was obsessed with the scene’s unwritten rules: no photos, no Shazam, no requests, and no touching or staring at others without consent. As a social environment, hyperpop breaks most of these rules. If the typical rave is a parasocial meritocracy – where the space you earn on the dance floor reflects the kind of energy you put into it – a hyperpop show is anarchic populism. Aesthetic dogmata are openly flaunted. Its artists, who often sing as well as produce, meld the naive self-consciousness of bedroom pop with the taunting cringe of dubstep, and what comes out is something aggressive, self-deprecatory, and refreshingly straightforward. This is in stark contrast from the typical house or techno show, which has a masculine urge for “deep cuts” that push its listeners to the frontier of obscurity. umru and company have no problem setting Young Thug against Evanescence, The Black Eyed Peas, Katy Perry, or Bladee; hyperpop’s trick to maintaining its dignity is not pretending that it’s cool in the first place. Pioneered by producers A.G. Cook and Danny L. Harle – who recorded modern classical compositions for Disklavier piano before founding PC Music in 2013 – their sound takes erudite compositional techniques and applies them to the gooey heart of the Western psyche.

The only common sonic motif of hyperpop is the glitch. To quote Nemesis: “The amplification of a dissonant signal creates distortion with artifacts (random sonic material accidentally produced by the editing process). These artifacts can themselves become an aesthetic. This is how we get deep-fried memes, quirked-up shawties, the weird-girl aesthetic, and Balenciaga.” One of my favorite parts of the night at any show is the dilation of this moment – the point where the DJs fuck with the sample so much that you question whether or not something has broken. Beats stop for longer than a typical rest or erupt over one another off-tempo. Tracks get artificially clipped, bumping up against the limits of their ability to be amplified, and vocal cuts become so warped that it sounds as though a system processer is shutting down. These moments draw attention away from the music as software (a recording, a document, an expression, a feeling) and toward music as hardware (performed and experienced in space). Doing so draws attention back to the embodied experience of a genre supposedly situated in the online condition. The glitch is where the software of that world and the hardware of this one rub against one another, generating friction.

Now, despite a new president and shittier weather, not much has materially changed, and I’m more resigned than ever to the fact that the future does not represent a massive departure from the present.

The upside of hyperpop is that it rehabilitates the music it feeds on: It’s now cool to admit you like the crap that got you bullied in high school. The downside is that it’s so dependent on recycling recent trends that it threatens to shrink the cultural lifespan down to an ever-tightening ouroboros: eventually, the snake is going to eat his own head. As this feedback loop closes, it’s reasonable to ask: Will the late 2010s (or early 2020s) even have time to crystallize as a set of styles and ideas before they come back to us in a more quirked-up form? But history’s endless regurgitation is not the same as its end. Like fractals in math, endless iteration creates its own wacky shapes, which, even at their most recursive, never really flatten out. Forms of modification take on stylistic effect: what was once an error now becomes a motif. Slowly, we arrive at a greater level of attenuation and modification at the forms our memory-objects take, following the ever-increasing force of the spin that makes them new.

Hanging out with the hyperpop kids sometimes gives me the same vertigo as zooming in on the infinitely iterable Mandelbrot set – it’s happening so fast, and it’s always the same. But just as Mandelbrot’s fractal is both a mind-numbing multidimensional form and a weird little bulbous shape, the actual aesthetic of the hyperpop scene, in defiance of its cannibal tendencies, is upbeat, inclusive, and profoundly non-judgmental. It’s reshaping a community that used to categorize itself by a discrimination against certain types of sound. Hyperpop is the reclamation of the wretched, the most ebullient outlook on the future in a moment when people are profoundly afraid that everything in the universe is approaching entropy. Hyperpop doesn’t promise a chrome-plated tomorrow, gliding to new worlds on the cool fusion of techno. Instead, hyperpop dons a supremely down-to-earth hacker mentality, taking scraps of the familiar and fusing them together to make something new, something just a bit weirder.

Fourtnight Battlepass peform at Rash NYE, New York, 2023

For a long time now, I have sort of hated New Year’s. I was in denial about it until recently because that shrinking part of me, my childhood, still had a retroactive hold over how I was supposed to privilege certain emotional experiences. But I’ve come to terms with the fact that, at twenty-four, I am an adult and have to occupy the world as such. Being an adult doesn’t mean you lose out on the parts of life that you enjoyed as a child, but it means that there’s no longer room for new and previously unimagined futures to sweep you off your feet. Another point of entry, another ethical or aesthetic way of being – these imaginaries diminish. Even during the pandemic, as I watched everything around me deteriorate in real time, there was some small hope that we would come out different on the other side, birthing some kind of new reality we hadn’t yet tasted. It didn’t happen. Now, despite a new president and shittier weather, not much has materially changed, and I’m more resigned than ever to the fact that the future does not represent a massive departure from the present. Instead, things are just going to get more and more quirked up.

Once the shock of newness dissipates, you can approach a thing from many angles, or from several at once. The exhilaration of first feelings gets replaced by an ironic detachment, which in turn is swallowed up by heartfelt appreciation. Maybe the phenomenon of hyperpop is just a sign of our ongoing boredom with the tropes of modernity, as we slowly admit to our inability to surpass them. We depend on many things we are no longer satisfied with, because we have not yet found a way to move on. In that sense, losing our youth means accustoming ourselves to this familiar version of things and, instead of daydreaming, making the most of what’s on hand. That, to me, is the great triumph of this music: it’s not particularly new, and it doesn’t fetishize mysterious pathways to the unknown; instead, it manages to keep us close to the heart of a childlike joy, rousing, if only through brute force, the rush and fever of what it was once like to experience something for the first time.

At midnight, I danced a little harder. All around me people, were jumping and cheering. Strangers kissed each other. It was nice. The first seconds of 2023 didn’t feel all that different from 2022 – or from any other night that I’d spent in the club over the past several years, for that matter. There were smoke machines, trashed bathrooms, and too little water. The floors were sticky in one or two places. The DJs I love, umru included, try really hard to give their listeners something to make their nights memorable, but there’s no great perception that any of it needs to be groundbreaking. In fact, it’s all a bit familiar, and thank God for that. Here was an entire internet’s worth of style and sound, barreling at us through the speakers like an avalanche, and all it wanted to do was play the hits. Here was something old, now just a bit glitchier.

___