Ian Cheng’s latest film – presented by Light Art Space at Berlin’s techno mecca, Berghain – is set in a little too fast paced future where artificial intelligence is wired to the human nervous system. Drawing on current consumer trends that shelve happiness as a product and ever-expanding use values of technologies, the film imagines a world tarnished by emotional refusal and parasocial relationships, but also one where tech is a way to negotiate and gain agency.

Ido Nahari: Do you think technology can be used to elevate our anxieties caused by it?

Ian Cheng: Yes. Zoom saved me and my team during Covid and allowed us to focus on the anime series Life After BOB (of which the film The Chalice Study is part) during an otherwise very anxious and distracted time. If I can generalize, most of our collective anxiety is due to the state of the world, our over-awareness of the most hyperbolic stories, an overall feeling that the larger super-agent that is our culture has no future plans. Conversely, anyone working in or around tech, be it crypto or AI, has a future that is quite defined and specific to work toward. Working on crypto or AI is probably an anxiety-proof activity.

IN: The film centers on the character of Chalice, a child implanted from birth with a Destiny BOB by her father, who spearheaded the development of the artificial intelligence guiding her through various emotional and psychological challenges. Since The Chalice Study focuses on the struggles of negotiating the presence of technology in her life, I wanted to ask you if you think that children are more susceptible to technological manipulation due to our assumed innocence of them, or is their heightened sense of imagination is actually what allows them to claim independence from it?

IC: Writer and comic radio dramatist Douglas Adams said the technology you are born into is like nature to a child. The technology that emerges between fifteen and thirty-five is something you can make a career out of; the one that emerges after thirty-five is a vulgarity and signals the end of the world. I wrote Chalice with this in mind – for her, having BOB co-pilot her life is something she takes for granted. The dramatic problems really arise when her father Dr Wong begins to favor and fall in love with the BOB-controlled version of Chalice, and “make a career out of it.” Dr Wong is finally seeing his invention take off, and Chalice begins to feel jealous, and also obsolete. When I look at my own kids, of course I worry what will happen when they inevitably get hooked on the high dopamine loops optimized into whatever the future version of TikTok is. This is a new technological phenomena, no doubt, as is the experience of being more and more a neuron in an internet enabled super-brain. On the other hand, as a parent, it clarifies to me the requirement for any person to work on themselves, their own self-confidence, their own sense of body, their own sense of capability and agency. Because the alternative to try to hide new technologies from children, make it forbidden or make them naive to it, is a Sleeping Beauty blunder.

Still from Ian Cheng, The Chalice Study, from the series Life After BOB, real-time story and simulation, sound, 50 min. © 2021 Ian Cheng

IN: Do you think that separation of humans from technology is a certain desirable political goal?

IC: I think I mean any successful navigation of the future requires an integration of opposites. In this case, of addictive (but relevant) technologies and a child’s physical abilities and in turn self-confidence. It’s impossible to separate people from social media, AI, or crypto.

I used to have a therapist, and I asked him, What’s the point of therapy? How would you sum it up? And he said to integrate all parts of yourself, including the dark parts, the addictive parts, the parts you don’t like. I think this is true of culture too, and the parental responsibility toward children.

IN: I’d like to poke you a bit more about your holistic approach, and wonder if this has anything to do with the possibility of attaining an NFT once the exhibition concludes – a digital identifier that became synonymous with the self expression of its owner. But doesn’t that identification contradict with the film’s ambition to avoid this sort of unanimity between individual and technology? For example, Chalice’s ongoing ambition and struggles to separate herself from her BOB.

IC: In the end though, Chalice realizes that parts of the life BOB lived for her between ages ten and twenty are now intrinsically a part of her, baked into her muscle memory and reflexes, whether she likes it or not. And rather than rejecting it or fighting it, she accepts it and we end on her trying to integrate the parts of her life that BOB left to her.

The True Name NFT that you can claim at the end of the exhibition is based on the I Ching (the ancient Chinese divination text Book of Changes) that some call it the equivalent of ancient software, and it was about reflecting back to the viewer something specific about them, a gift and a shadow, that could be integrated into their true super power, or “true name.” It was a gesture to have some part of the show adapt itself to each and every viewer, and give them a boost, maybe some clarity, or at very least something to chew on. It was also played on a part of the film where Chalice tries to rename herself and visualize how even just a different name might rewrite her destiny. The underlying thing I’m obsessed with in making Life After BOB is existential health – how can a person find a path for themselves amidst technological change and a divisive culture.

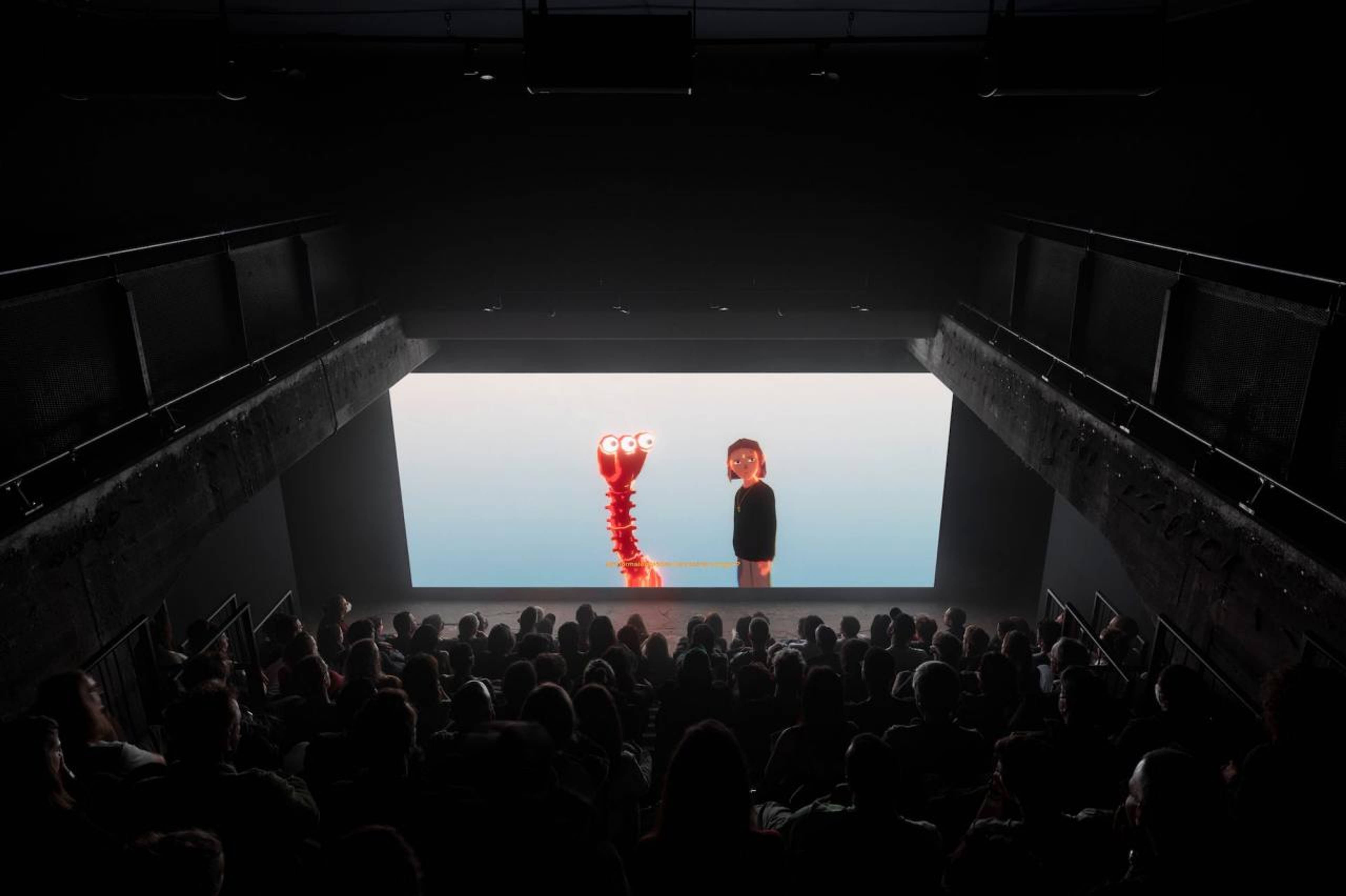

View of “Ian Cheng: Life After BOB,” Halle am Berghain, Berlin, 2022, presented by LAS (Light Art Space). © 2022 Ian Cheng. Photo: Andrea Rossetti

IN: It’s great that you mention play, because I wanted to ask you about that. The Chalice Study is infused with and influenced by your previous works of live simulations that verge on aesthetic, narrative, and experiential elements of gaming. But since the film tells of some social and psychological calamities, is there a way of avoiding the trivialization of catastrophe when it is introduced by play?

IC: Are you asking why I made The Chalice Study using a game engine, and in a cartoony style?

IN: Yes, and even more specifically, what are the ways that a playful style (such as a game engine or cartoon elements) could even inform us of social and psychological calamities.

IC: I love Miyazaki – Totoro, Princess Mononoke, Ponyo. My kids love Howl’s Moving Castle. Miyazaki explores a lot of complex themes and human behaviors in his films, and the fact that it is done in imaginative animation makes me surrender and ease into its complexity. Kids can get into it more easily too and I find this inspiring. Animation is a great trojan horse to explore the complex and scary troubles of our time. Secondly, I wanted the specific challenge of building a movie in the unity video game engine. It hasn’t really been done before. People have made short ten-minute films in unity, but never a fifty-minute long film. Doing it in a video game engine, having it render live in real time, made directing an animated film feel so much more amenable to revisions and iterations compared to the traditional 3D animated pipeline. As a director I could be changing shots, sets, lighting up to the day before an opening. No animated production before has this flexibility and iteration speed. It’s hard to appreciate this as a viewer, since as a viewer you should not care how the sausage is made, it just either works or it doesn’t. But for me as an artist, it means I could actually make a fifty-minutes-long animated film, at a fraction of the price of equivalent animated film of that length and scale. Making a film in a video game engine now feels closer to making software – where you can iterate, publish updates, easily share the codebase for bootstrapping future projects.

IN: Going back to your point about making software, all forms of artificial intelligence presented in the film are programmed to be motivated by utilitarianism – the philosophical doctrine that correlates the maximization of happiness with societal progression. Would that mean that misery is a form of assessing and asserting our humanity, as is the case with the character of Orlando in the film, who fails to assimilate to his Destiny BOB and is emotionally devastated as a result?

Parents quite literally program children, and have an unavoidable influence on their entire life script, their anxiety or their comfort, their sense of trust and mistrust toward the world.

IC: Orlando is a broken person in the film, but it’s not because he is unable to achieve happiness. It’s that he incorrectly seeks happiness as a goal. Whereas Chalice – at least in the end – seeks growth, what I’ve been phrasing as “integration.” And integration is a more satisfying and meaningful organizing principle for life. Orlando exists in the story for Chalice as an image of what not to be, a tempting path that leads to existential failure.

IN: Not to give too much away, but the relationship between Chalice and her father is spoiled by his insistence to regard her as an experiment. In order to assert the normality of their relationship, he iterates that it is a natural course of events, since parenting is programming. If that is the case, then what is education, and how can we deploy pedagogy in our associations with technological progress?

Still from Ian Cheng, The Chalice Study, from the series Life After BOB, real-time story and simulation, sound, 50 min. © 2021 Ian Cheng

IC: I wrote “parenting is programming” in the script without any cynicism. I actually believe that is true. Parents quite literally program children, and have an unavoidable influence on their entire life script, their anxiety or their comfort, their sense of trust and mistrust toward the world. But the critical thing most parents forget is that their role as parents, and the stuff they “programmed” into their kids, is scaffolding to get through the early years. But scaffolding is meant to fall away, and most parents don’t know when to let go of their kids, to stop parenting them, to let go of their role. And there isn’t much cultural guidance to help with modeling this type of letting go. In fact, many cultures still require an unhealthy attachment and debt to be constantly connected to one’s parents. I personally have anxiety about not being able to let go when my kids grow up, so I think about this a lot. I guess to answer your question, future education should include modeling how to exit; how to detach from one’s parents, one’s teachers, one’s coddling institutions, and go out and try things and fail and have adventures. Get some scars. Schools should have built-in “anti-school” prep, as counterproductive as that might sound to the big business of schools.

IN: It’s true – we all find ourselves in the bind of learning to unlearn certain conditionings. But I fear that educational process will become ostensibly harder when AI is in the driver’s seat of consciousness. Speaking of which, if AI determines humanity in The Chalice Study, do you think simulation will determine what we consider to be natural in the future?

IC: I think simulation is very important. Simulation is already what we do in our own minds, whenever you recall a memory or envision a possible plan – it is already a big part of how we organize our present condition to a future state. So simulation that is technologically achieved will only extend our inner simulation abilities even more, and make it more shareable, multi-player, playful. Moreover, some things are too complex to simulate in our own imagination. It is hard to play out ecological problems purely in our head, or to imagine ten seasons of a TV show plot without a writers room. So the more simulation tools we have, the bigger complexities we can work out.

View of “Ian Cheng: Life After BOB,” Halle am Berghain, Berlin, 2022, presented by LAS (Light Art Space). © 2022 Ian Cheng. Photo: Andrea Rossetti

View of “Ian Cheng: Life After BOB,” Halle am Berghain, Berlin, 2022, presented by LAS (Light Art Space). © 2022 Ian Cheng. Photo: Andrea Rossetti

IAN CHENG (*1984, Los Angeles) is an artist living in New York. He has exhibited widely including solo presentations at MoMA PS1, New York; Serpentine Galleries, London; and Julia Stoschek Collection, Berlin. Since 2012, Cheng has produced a series of simulations exploring an agent’s capacity to deal with an ever-changing environment. Most recently, he has developed BOB (Bag of Beliefs), an AI creature whose personality, body, and life story evolve across exhibitions, what Cheng calls “art with a nervous system.”

IDO NAHARI is a sociologist, researcher, writer, and editor for Arts of the Working Class.

“Ian Cheng: Life After BOB”

LAS Light Art Space

Halle am Berghain, Berlin

9 Sep – 6 Nov 2022