I. Alex and Henry

I was single, it was the pandemic, and there was nowhere for my yearning to go. I spent days reading books in my parents’ backyard, stretched out on an old comforter next to a garden shed filled with lawn-torture devices, and when you read books in long stretches like that, it can hit you like a drug, or a truck.

Casey McQuiston’s Red, White & Royal Blue (RWRB, 2019) was a truck – a bedazzled, rhinestone-covered eighteen-wheeler. I first read the novel before it was adapted into a made-for-Amazon Prime movie in 2023. I learned of it from a Kindle ad, read the download in two days, and rushed to write down my thoughts on Goodreads immediately after, worried that the book’s effects would wear off if I didn’t capture them.

Omfg this book fucking obliterated me, I wrote. It filled me with such longing that I felt like my chest was going to burst. It's an itch that's more diffuse and heavy than just lust, like some sort of organic, long-running MDMA that gilded my bones with mercury and gold.

Goodreads was an outlet for all the social interaction with people my age that I wasn’t having. My friend Julie had introduced me to the site a few years previously – it had been the very first “criticism” I had written at age twenty-two. We wrote for an audience of each other, plus a few friends, like a book club stretched out over space and time. When you finished a book, or even if you didn’t, you wrote something about it, and others would see it on the way to typing out their own reviews. Even if Goodreads has become an industry menace, for me, the site was a release outside of the more structured outlets for art criticism. It was writing away from the concision fetish of editors; it left me free to sprawl inelegantly across ideas. It fostered an unselfconsciousness rivaled only by my email drafts and Notes app.

RWRB was my first introduction to the gay romance novel, and to the gay romance novel’s tropes. It takes place in an alternate world in which Trump loses the 2016 election to Ellen Claremont, who becomes the first woman ever elected president. I describe it as an actually well written rom-com dressed-up fan-fic of a love story between the First Son of the United States, Alex Claremont-Diaz, and the Prince of the UK, Henry Wales.

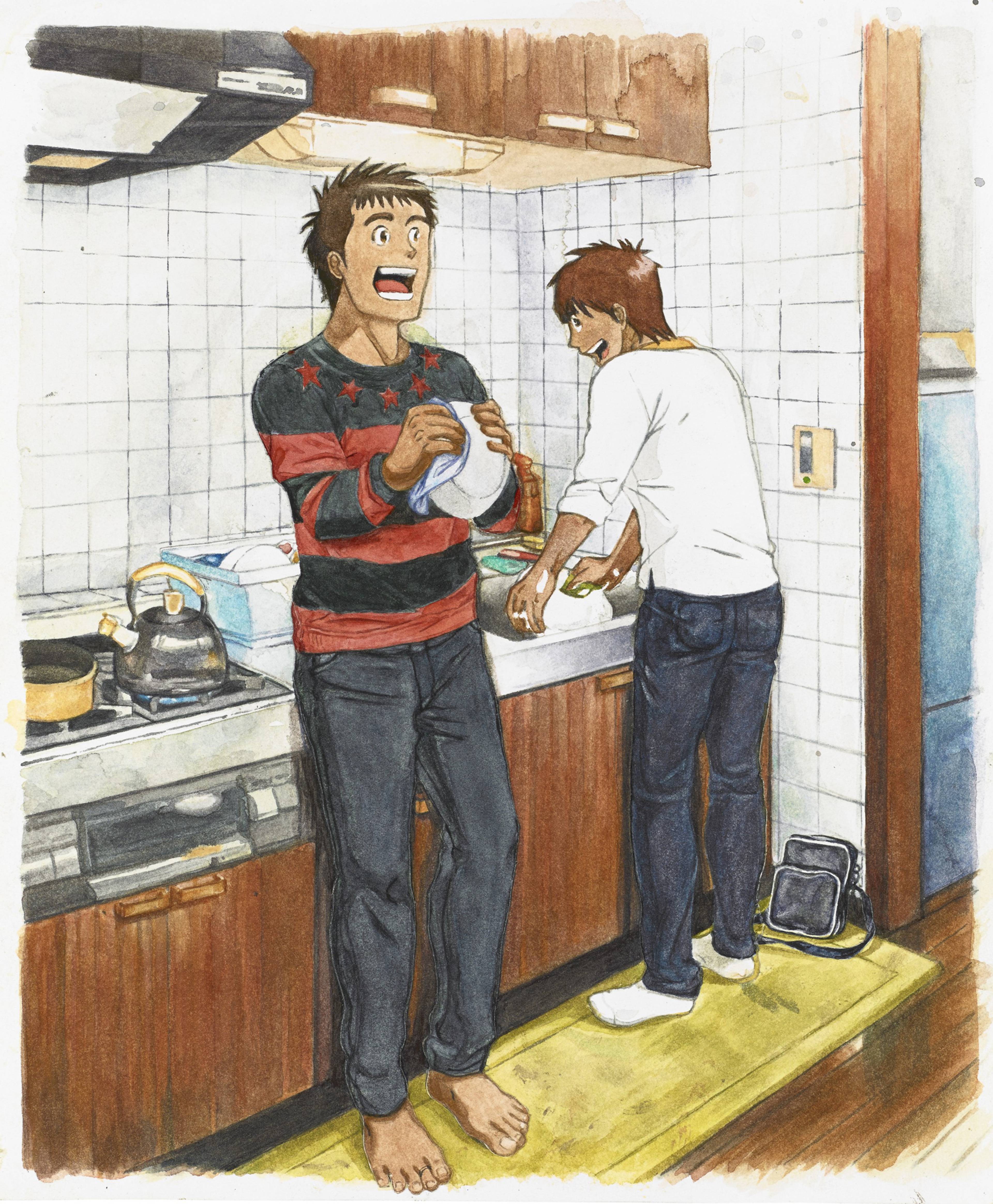

Still from Matthew López, Red, White & Royal Blue, 2023, 118 minutes

Alex (tan, curly-haired) “hates” Henry (blonde, blue-eyed).He has hated his “fakeness” for much of his life, while also being basically obsessed with him, until a press event catches them in a fight and forces them to spend more time together in order to repair the international PR between the UK and the US. When Henry suddenly kisses Alex at a party, he “realizes” that he’s actually bisexual. (This I wasn’t sure I believed. Like what a trope of the straight guy who just “happens to be gay” after getting a kiss. Like whatever maybe I'm erasing the experience of bi people but how the fuck did he not know at all?)

Henry and Alex quickly fall into this ridiculous love affair. Late-night calls, 24/7 texting, long-winded flowery emails, covert trysts –all while the guillotine of coming out publicly without jeopardizing their respective families’ political prospects hangs over them (Alex’s mother is running for re-election, Henry’s grandma, the queen of England, is obv super conservative). Lots of sneaking around sex in sketchy places nights in Paris bathroom blowjobs. All hot and great and lusty.

A lot of the book is just correspondence between them, lascivious and witty. Usually, it’s super cheesy, but I could. not. stop. smiling while I was reading. Part, just a small part, of why this was so affecting I think is because it reminded me of when I was in a secret relationship with this boy also named Alex in high school and man we used to send ridiculous good night and good morning texts to one another. Like fuck the stupidest shit. Here’s a slip of some of the email that Henry writes to Alex:

“Should I tell you that when we’re apart, your body comes back to me in dreams? That when I sleep, I see you, the dip of your waist, the freckle above your hip, and when I wake up in the morning, it feels like I’ve just been with you, the phantom touch of your hand on the back of my neck fresh and not imagined?”

These passages filled me with a yearning that was difficult to masturbate away. I find this much more fantastically erotic than the physical BDSM stuff and heavy sex cruising things that are sometimes in a lot of gay literature, I wrote. Even when I get aroused by a sexy Garth Greenwell scene where he chokes on a dick and cries about his mom I can kind of shake that off but this was existential.

In the middle of suburbia during lockdown, I was addled by images of gay happiness that felt just out of reach. I am protective of The Boy I was when I wrote those Goodreads reviews, of the Boy who wanted to make the fantasy of gay romance novels real. Ah, this type of love that is like ... obliterating ... like beyond reason and thought, I wrote, Will I ever allow myself to feel this way about someone else again?! Should I! (Yes! Yes you should!). I was yearning for many things – sex, a relationship, friendship, intimacy – and RWRB was a silver-screen image of what I was missing.

What was the relation between the happy endings I encountered in literature and the happy endings I yearned for in my own romantic life? Did anyone have pointers on how best to “roam the greenwood?”

In his essay collection Love in a Dark Time (2002), Irish novelist Colm Tóibín questions why so little of gay literature gives its characters happy endings. “Why can’t gay writers give gay men happy endings, as Jane Austen gave homosexuals? Why is gay life often presented as darkly sensational?” He’s mostly talking about 19th- and 20th-century novels, but the same could be said for a particular vein of capital L gay Literature of today: Garth Greenwell, Alex Chee, and Ocean Vuong. Tóibín singles out E.M. Forster’s Maurice as exceptional, however, for the way the author allowed Maurice and Alec, the novel’s two gay characters, to forever remain in love as early as 1913.

Forster wrote about Maurice in his diaries, in an afterword that is now included with the novel:

A happy ending was imperative. I shouldn’t have bothered otherwise. I was determined that in fiction anyway two men should fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows, and in this sense Maurice and Alec still roam the greenwood. I dedicated it “To a Happier Year” and not altogether vainly. Happiness is its keynote – which, by the way … has made the book more difficult to publish. If it ended unhappily, with a lad dangling from a noose or with a suicide pact, all would be well … but the lovers get away unpunished and consequently recommend crime.

Tóibín singles out Forster’s phrase “roaming the greenwood” as a shorthand for a gay “ever after” that could survive in the space of fiction, but not yet in real life (at least publicly). Forster didn’t publish Maurice during his lifetime, fearing legal persecution, and the book was only posthumously published nearly sixty years later, in 1971. By then, Stonewall had changed the visibility of metropolitan gay life, and Maurice and its happy ending were politicized alongside other gay literature from the 70s that sought to produce blueprints for post-liberation happiness.

Unlike Tóibín’s subjects, however, in the last few years, there has been a profusion of gay narratives; some that continue to aspire toward realism and angst – the movies Alex Strangelove (2018) and Call Me By Your Name (2017), the TV series Looking (2014–16) – and others that deal conspicuously with happy endings – the 2018 feature Love, Simon (and its 2020 TV spin-off, Love Victor), the movie adaptation of RWRB, the TV adaptation of Alice Oseman’s beloved comic Heartstopper (2016–). Against Tóibín’s tortured past, I wanted to understand what the texture of this simulated gay happiness was that left my real life wanting. What was the relation between the happy endings I encountered in literature and the happy endings I yearned for in my own romantic life? Did anyone have pointers on how best to “roam the greenwood?”

The Song of Achilles (2011) fanart

II. Achilles and Patroclus

The pandemic opened up a little and I moved back to New York. Things got busy and I didn’t think about Goodreads for a while. I had resolved to approach dating with less manicness, which mostly meant I didn’t swipe at all hours of the day. The high of RWRB had fled my immediate mind. The meet-cutes of gay romance novels were replaced with the unyielding interfaces of dating apps, but the echoes of Henry and Alex’s infatuation had settled in my body like silt. It made my pursuit of a relationship feel more directed; I felt I knew more of what I wanted. A connection comes when you have accepted that it will come on its own time, I told myself, a TikTok-educated self-help guru.

I went on a date with a photographer who was from a city near my hometown. We had drinks at Branded Saloon on Vanderbilt Avenue in Brooklyn, behind masks, and we did not kiss. When he suggested we see a stand-up comedy show for our next date, I felt that we were too different, and I didn’t pursue another date with him. I took a month off after that, not discouraged, but staying true to my resolve of being less manic. A few weeks later, as the leaves began to evacuate their branches, I met a curly-haired boy at Covenhoven, around the corner on Classon.

At first, we, the Boys, were atoms, unsure of leaving our own nuclei of friends and women, but that first date dangled an escape. I arrived early to the backyard and tried to appear nonchalant by reading a book before he arrived. We stood awkwardly while we selected artisanal beers from a fluorescent case. Very mundane. But soon, our date was marked by a stunning coincidence: His roommate was dating an ex of my friend Julie. Together with the fact that we got along, and that he was adorable, it lent the date an aura of simulated fate, which, I realize, is how it feels when a date goes well. So, it went well. Then, it went really, really well. And then, it hurt to keep smiling so much.

With the Golden Boy, the pleasure is immediate, psychosomatic. You grin until your cheeks hurt; your scalp prickles until it might lift off of your head. Your tongue runs away from you. “This and this and this,” you say to him.

My relationship with Ekin did not share the staged meet-cutes of RWRB, but it had its own share of fireworks. I brought him a book from an exhibition I had worked on; he showed me his portfolio and introduced me to rakı balık (raki and fish), a Turkish tradition of sharing one’s sorrows over drink and then celebrating them away. Our descent into a relationship was different from fiction because so much was unspoken; we both pretty much knew we wanted to be with each other after the first date. It would have made for a terrible short story – maybe easy love makes for bad fiction.

We settled into a rhythm. I left a toothbrush at his place and identified the nearest gym. We perfected my bagel order at the breakfast shop nearby. When Julie threw a concert for an album she wrote about her ex, I invited him; when his friends Derin and Talya visited from Turkey, we went to the Rockaways and discussed star signs on the beach.

My brother Nick gifted me The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller (TSoA, 2011), and it unsuspectingly reawakened the literary infatuation I had first encountered with RWRB, this time post-singledom. If RWRB was the truck, this was definitely the drug, the drug that put me back on the Goodreads wagon.

Now, the Boys are in Greece. It’s antiquity, but the emotions are American high school: The golden Boy is Achilles, essentially a Harvard-bound football senior, good at everything. He has curly hair and nice feet. He’s popular, in mythic proportions. He is a god training to be a killing machine in an epic war. The other Boy, Patroclus, averts his gaze when Achilles comes around. Patroclus is the narrator, and he is just a human, a curly-haired, olive-skinned boy (Achilles is, of course, blonde; the two genders of gay romance). He sees himself as weak and mortal. An exile with no family and no name. This is you, Patroclus, you worthless piece of shit.

Still from I Cannot Reach You, 2023–, television series

But Achilles loves you. He takes a liking to you, improbably. Invites you to sensually eat grapes. To join his training to become a war machine with a centaur. You swim together. You skip stones. The sun shines, and a feeling rises in you that you cannot find the words for. Growing up a dejected son of mortals, the highest pleasure you have found is the absence of fear. What happens now that you are overwhelmed by pleasure? With the Golden Boy, the pleasure is immediate, psychosomatic. You grin until your cheeks hurt; your scalp prickles until it might lift off of your head. Your tongue runs away from you. “This and this and this,” you say to him.

I can’t even start another book because I don’t want to leave the world of it. I’ve been walking around in a daze and huffing snippets of the book to remember what it was like to be inside, I’ve been trying to figure out exactly what it is. It’s not horniness; it’s deeper and harder to fulfill. It’s like a romance boner, or romance wetness, whatever you want.

Achilles and Patroclus’s infatuation is manic, epic, and unreal, and I was entranced. So much so, in fact, that I looked up TSoA fan fiction. I even returned to the fandom of RWRB, which was now being turned into a movie, and learned that it was also based off of fan fiction (a now hard-to-find, anonymous PDF called Carry It In My Heart, a love story between Jesse Eisenberg and Andrew Garfield on the set of The Social Network (2010) that McQuiston has worked hard to bury. But sing, unburied, sing: I found it). The simulated infatuation of TSoA opened a deeper well of romance within me, and I wanted to understand the technical and historical contours of these fictions.

Still from Heaven’s Official Blessing, 2023–, television series

The Song of Achilles is, as Miller has herself described, something like gay historical fan fiction. It is a retelling of the Trojan War as a love story. “Fan” is a key descriptor here, because it mirrors the genre of fiction that speculates homoerotic relationships between male characters in pop media where the relationship is implicit or imagined. Gay fan fiction is distinct from gay fiction à la Chee, Vuong, or Greenwell because it’s explicitly fantasy; it’s concerned not with the realistic representation of gay life. It is heightened for salaciousness. It is the pleasure of gay love without the annoyances of lived, gay culture.

As the grand doyenne of internet philosophy, ContraPoints, says in her three-hour-long video essay on Twilight and the genre of romance fiction, the plot of a romance novel is driven by the barrier of the love interests being together. The plot continues until the barriers are removed, or at least abated, but the barriers provide tension and release. A simple barrier is a difference between immediate physical chemistry and competing lifeworlds: Achilles is hotheaded and Patroclus is a pacifist; he is a God and you are a mortal. In RWRB, it’s about the closet, and the negative PR Alex and Henry fear from their parents. These barriers make the Boys’ trysts more daring and hot; they make their sex urgent rather than wasteful, as if their time together should be cherished because it is has stakes. Queer romance novels are often tasked with an additional barrier: being both romance novels and coming-out novels. A sexual awakening is usually instrumentalized to the reader’s titillation; you are the catalyst that sometimes jump-starts a lover’s sexuality – you’re So Hot You Awaken His Feelings.

When those barriers are gone, the plot is resolved, and there is no more narrative drive – they are together. This is why it is often so difficult to find pointers on how to “roam the greenwood” from gay romance novels. It is definitionally against the formula of the genre: They expend so much of their narrative energy surpassing the “barriers” to initially being together that they don’t provide much guidance for the tribulations of being together afterwards.

Gay love is a genre of forbidden love. It is the feeling of both possessing perfection and being totally desired, or, as my friend Clare has said, “the feeling when a hot person is obsessed with you.”

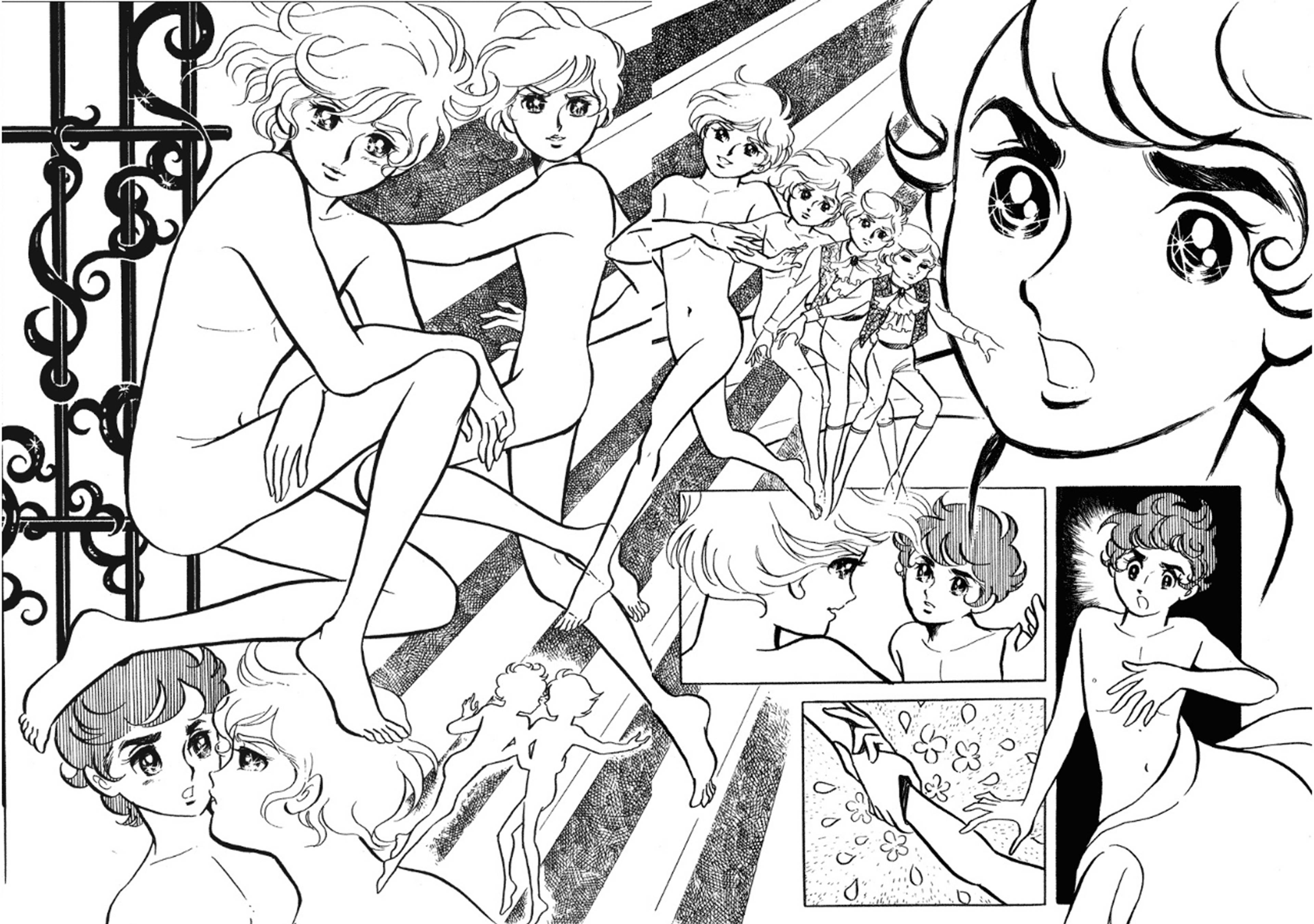

In its soft, romance-forward representation of Achilles and Patroclus, I wondered if TSoA wasn’t a distant cousin or stepchild of another genre of gay fiction: Boys’ Love (BL), or yaoi, a genre of fictional media coined by manga artists Yasuko Sakata and Akiko Hatsu in Japan in the 1970s. A portmanteau of yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi (“no climax, no point, no meaning”), yaoi referred to texts that focused on sex to the exclusion of plot and character development. It typically features homoerotic relationships between male characters, and unlike bara, which is homoerotic content primarily for gay males, yaoi is written primarily for female readers.

I did try my luck with some real Asian BL. On my friend Anna’s suggestion, I watched the popular Chinese BL series Heaven’s Official Blessing (2020). On my friend Alberto’s suggestion, I downloaded a Rakuten account and watched HIStory 3: Make Our Days Count (2019), where the popular school bully falls inexplicably in love with the poor nerd. With Ekin, I watched Netflix’s I Cannot Reach You (2023), a Japanese BL of essentially the same plot. Each episode was essentially the build-up to one or two key “will they or won’t they” moments: well-timed falls, scandalous hand placements, love interests with overwhelming, almost animalistic urge to desire you and a tendency to stalk the school nurse ward (the only place there can be a bed for children). I Cannot Reach You gets points for filming those moments in slow-motion and timing them to an EDM drop. I admit to feeling some pussy quivers. But it also all felt, as Julie says, “dick-less”: The most contact you get is a hug or a salacious handhold, and the love interest is essentially straight but somehow turns gay. Yaoi / BL is too vast and multiversal a genre to summarize, but I did have the feeling of observing a distinctly female medium in those shows, in which Boys are a kind of platonic essence, to be molded into a fantasy of soft, effeminate, non-threatening romance.

Spread from Keiko Takemiya, In the Sunroom, 1970 (apparently the first-ever yaoi)

TSoA isn’t technically yaoi. Afterall, its plot holds other desires beyond just sex between boys. But, it does lean on some of its key tropes: Achilles is straight, but he’s gay for you, as if his love were so oceanic that it transcended biology and gender. Achilles is perfect, and you are a total loser, but he plucks you out of obscurity by the power of recognition. To be the reader is to be beloved, to be enveloped in this simulation of unconditional love. Neither Miller nor McQuiston write with the expectation that their stories are consumed entirely for women, but both TSoA and RWRB are extremely popular with women, sometimes more so than with actual gay men.

In the 1970s, debates raged about whether yaoi was a deleterious or unrealistic representation of gay males in Japan, echoing Stonewall’s politicization of gay literature as producing blueprints for gay happiness. In the surprisingly vast academic discourse on yaoi and gay representation, some scholars have argued that yaoi is a problematic co-optation of gay-male dynamics for female eyes. Others argued that it is fantasy, and that it isn’t meant to be a direct representation.

Because gay media is still relatively sparse, I sympathize with the frustration that more of it should be for gay people. But I also don’t think that fiction should always be tasked with being a mirror; fantasy and real life need not be the same (I think of sick, twisted fiction like Dennis Cooper’s The Sluts (2004), which explodes those categories). I have also sometimes felt oddly well represented in the goofy emotional dynamics of BL – even though I could never imagine acting that way. Regardless of who it is written for, BL and gay romance hinge on the effective evocation of unconditional love and radical acceptance. This is a dynamic that is heightened by the circumstances of same-sex relationships, but not exclusive to them; gay love is a genre of forbidden love. It is the feeling of both possessing perfection and being totally desired, or, as my friend Clare has said, “the feeling when a hot person is obsessed with you.”

“There isn’t a single girl that hates gay men!” Ōno proclaims in the manga Genshiken (2002–16)

III. Charlie and Dev

My friend Christine and I got expensive salads in Midtown and ended up talking about romance novels. She told me about a friend who had become obsessed with them, holing up in her apartment and reading them nonstop. Eventually, the infatuation she encountered in the novels prompted her to re-evaluate her relationship. She realized that she was not in love. There were other reasons too, Christine added, but she decided to leave her boyfriend partly because of romance novels.

“Oh wow,” I said.

In contrast, Christine felt that her relationship was validated because her partner made her feel the way the books did. If the infatuation one encountered in a romance novel was not happening in one’s own relationship, should you leave to try to find it?

“No,” Christine said, laughing, and I agreed. “I mean, it depends on other things. But generally, no,” she said. “Really, those books are just lodestars for helping you recognize infatuation in your life when you experience it.”

I hadn’t read a romance novel in a while. Ekin and I went to grad school in separate cities, and I missed him. He sent me Instagram reels of Turkish-Asian couples. We spent breaks and summers together in New York, Istanbul, and Japan, our connection sustained by Facetimes and phone calls.

On a trip to Reno, Nevada to visit my friend Alberto, I picked up a book that Julie recommended said the Goodreads algorithm suggested for lovers of RWRB. I bought The Charm Offensive (2021)by Alison Cochrun on my way to a cabin near Donner Lake and read it in a day or two. The Charm Offensive helped me test out this “lodestar” hypothesis.

So Dev is the 6ft 4in Indian-American producer on the set of something like The Bachelor and Charlie is the Prince Charming for this new season, I summarized on Goodreads. Dev is a hopeless romantic who sets up fairy tale endings for other people but doesn’t believe that he is worthy of his own. He is set to be the handler for Charlie, a very pretty, socially-anxious tech-billionaire and future Bachelor. Charlie is written as a “literal baby” and improbably, salaciously, develops a golden retriever-like attraction to Dev. The book switches between the perspectives of these two Boys, artfully keeping each perspective in close-enough third person to sustain each character’s ignorance of the other’s affection. Gradually, of course, Dev and Charlie fall in love, and navigate the mess of being on this show together, as well as their respective personal neuroses.

At one point in the book, as is customary after Boy meets Boy, Boy loses Boy, and Dev and Charlie break up. This is mostly because neither of them believed that they deserve love – there’s a whole mental-health storyline we don’t need to get into – but a friend tells Dev something that stuck with me: Fairy tale endings don’t just happen to you, she says. They are something that you decide you want for yourself and make happen.

In the context of the book, the advice is an impetus for Dev to go out and get Charlie back, which – to the author’s credit – he doesn’t take, instead swerving deeper into his depression. It takes Charlie entirely rerouting the course of the show and coming out on television to get Dev to come back around.

Still from Heartstopper, 2022–, television series

For me, what this emphasized was a rarely spoken-about aspect of romance novels: that they are somewhat educational. They teach you what you do and don’t want about romance, and give you a roadmap and a set of emotional milestones. I was unimpressed by the idea of a grand gesture to prove love, but I liked how carefully Dev carved out space for Charlie’s interests. The idea that you make fairy tales happen lent more agency to happily ever after than just waiting around for it.

When I finished, Alberto and I were sunbathing on a dock over Donner Lake in our winter coats. The sun poured down on a chilly spring day. I handed the book to him and made him promise to read it sometime. Alberto really is a wonderful friend. He had planned the trip to his hometown meticulously. Our friend Rosa came too, and we had a reunion snowshoeing and fly-fishing. We had all-you-can-eat sushi and watched the Twilight movies. It had been years since we’d been able to spend time together, and, flushed with the residual high from The Charm Offensive, I felt aglow with gratitude for how we had actively maintained and cherished our friendship.

When I turned to Goodreads to process my feelings about the book, that word stuck with me: cherish. It’s not a word that is used with a straight face much anymore, unless the words you use are somehow doily-laced. What does it mean? It means to hold with love and care. In The Charm Offensive, Dev is manic and Charlie is calm; Charlie’s favorite activity is to do puzzles, and Dev complies because it makes Charlie happy. Charlie, in turn, is taken to a gay bar with Dev (purportedly his worst nightmare). Cherishing sometimes looks both like doing the things you like and becoming willing to do things you don’t because someone else does. But it also has connotations of gratitude that you have the opportunity to love and be loved. That you have a recipient for your care and attention. The word also recalls the idea of holding something with both hands. One cherishes ideas and friendships and memories.

Last September, my relationship with Ekin hit the three-year mark, the initial infatuation settling into something more stable. Our relationship was not staked out by the grand gestures and conventions of the gay romance genre, but that didn’t mean that the genre couldn’t provide some ideas. For example, that cherishing one another might mean the gradual collection of each other’s idiosyncrasies, and the joy of anticipating them: Grazing throughout the day, occasionally, even though I prefer to eat three large meals, or getting a warmer comforter, even though I sweat like crazy and he is cold but radiates heat. They were trail markers in the landscape. Our greenwood felt larger and lusher, but I didn’t feel as unsure about my path through it. We left the lake, and I left The Charm Offensive in Reno. On the flight back East, I thought about who I’d text when I landed. I would text my mom; I would text Ekin; I would text Julie, Alberto, and Rosa. And when the plane touched down, we’d roam the greenwood together.

___