Two years ago, I received an Austrian passport. Before 2020, multiple citizenship had not been permitted in Austria; now, there was a new law making an exception for descendants of victims of Nazi persecution. Soon after Brexit – my siblings and I were born and raised in the UK – my dad began gathering the necessary documentation for our applications. At the time of the Anschluss, his father’s father, Walter Schwarz, was a wealthy Jewish businessman, manager of the family department store, and owner of an art gallery in Salzburg. He and his wife, Dora, were fervent Zionists; in the early 1930s, she left him and took their three sons to Palestine. Walter stayed behind with his mistress. He was arrested by the Gestapo in March 1938, released in August, and re-arrested while trying to flee to Switzerland. His death in the headquarters of the Munich SS was recorded, though the circumstances have been disputed since, as a suicide by hanging on 1 September 1938. The department store and his other assets, including an art collection, were all “Aryanized” – stolen by the state.

My great-grandfather’s survivors initiated restitution proceedings soon after the Second World War ended. They received financial reparations from the Austrian government, although a fraction of the calculated value of what was lost, and regained ownership of the department store, which they sold in 1962. The main location of the Kaufhaus Schwarz, on Alter Markt in central Salzburg, is now a Louis Vuitton store; two bronze Stolpersteine, or stumbling stones, record this history and my great-grandfather’s fate. The expropriated artworks were returned in stages: one batch, held in the Upper Austrian State Museum in Linz, in the late 1940s, which my grandfather quickly and cheaply sold; another, more valuable group of works on paper, mostly by Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt, was discovered in the same museum in the 1980s and, likewise, returned and mostly sold – the money from this, I’ve been told, was poorly invested. Other, unidentified artworks are still thought to be missing.

Restitution is not simply about restoring property rights, but a search for truth and justice in response to irreparable loss.

When I arrived in Salzburg in early September, I showed the border official my Austrian passport and, with my non-existent German, tried not to feel like an imposter. I was visiting for a residency at the Salzburger Kunstverein, where a group exhibition, “The Museum of (Non)Restitution,” had been organized in collaboration with the Salzburg Museum. Three artists – Sophie Thun (*1985), Tatiana Lecomte (*1971), and Thomas Geiger (*1983) – each contributed new work. Their subject was the restitution of Nazi-looted art and other properties: a process that, as the show’s title indicates, is ongoing and will perhaps always remain incomplete.

The impetus was a case of lost artworks: a pair of canvases by the 19th-century Austrian painter Hans Makart, taken from the National Museum in Poznań during the Nazi occupation of Poland. In 2023, the institution contacted the Salzburg Museum, where two seemingly identical paintings attributed to Makart – mythological scenes depicting a mermaid in the sea – were on long-term loan from the Raiffeisenlandesbank Oberösterreich. Only then did curators in Austria realize that the works were unsigned copies after the original. There was no restitution, but new information had been uncovered.

Top left: Studio Hans Makart, Mermaid with Fishing Net (Back View), 1871/72, oil on canvas, 127 x 163 cm; top right: Studio Hans Makart, Mermaid with Pearls, 1871/72, oil on canvas, 129 x 171 cm. Both © Salzburg Museum (Loan der Raiffeisenlandesbank Oberösterreich). Below left: Sophie Thun, http://lootedart.gov.pl/en/product-war-losses/object?obid=5972, 2025, silver gelatin print on baryta paper, 127 x 176 cm; below right: Sophie Thun, http://lootedart.gov.pl/en/product-war- osses/object?obid=5973, 2025, silver gelatin print on baryta paper, 127 x 176 cm. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com.

Thun’s contribution to the exhibition includes an installation of the paintings, now reattributed to the “studio of Hans Makart,” hung above enlarged, black-and-white photographs of the (still missing) originals. Next to this, she has placed a cabinet from the Salzburg Museum, previously used for displaying toys. Peepholes allow partial glimpses of a collage of photographs of other Nazi-looted objects – paintings, sculpture, furniture – which have not been located.

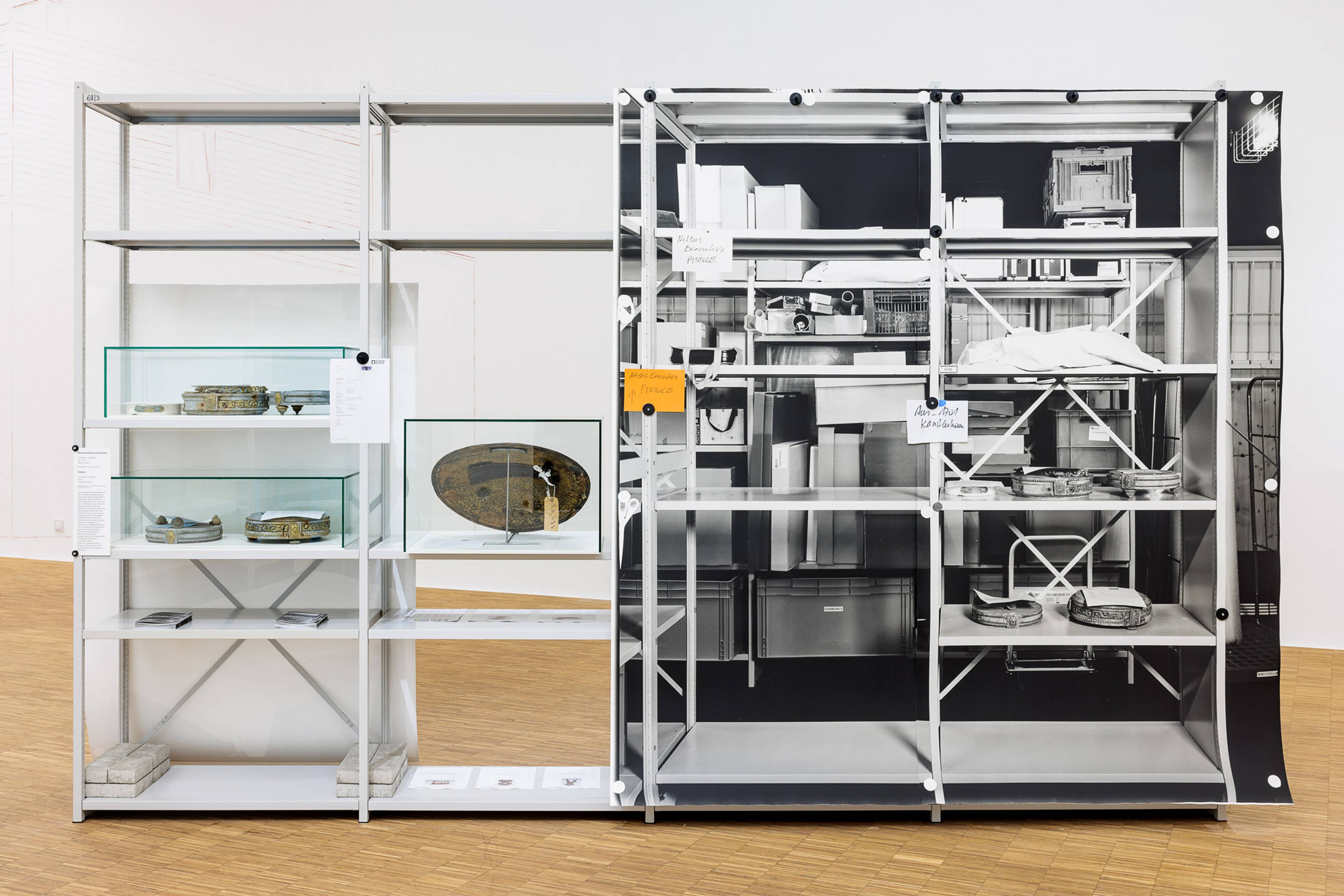

In another work, Thun turns to the successes of diligent provenance researchers like Susanne Rolinek, who has identified multiple Nazi-looted works in the Salzburg Museum’s collection. (Rolinek is also one of this show’s curators.) A recreation of a large metal shelving unit in the stores of the Salzburg Museum displays objects awaiting physical restitution: A group of pedestals and plinths from the collection of Alphonse and Clarice von Rothschild, I was told, may be returned during the exhibition; other items, already restituted, are represented by photographs and print-outs of their museum database entries.

Sophie Thun, Bereitstellung (Provision), 2025, silver gelatin prints and photograms on baryta paper, magnets, shelves, detail, with various restitution objects of Salzburg Museum. 2025. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com

Tatiana Lecomte’s project shifts the focus to an individual story. A fold-out leaflet of photos and textual sources reconstructs the life of the Jewish-born Austrian painter Helene Taussig. A convert to Catholicism, Taussig was nonetheless deported to a transit ghetto in Poland, where she died in 1942. One of her few surviving paintings, the brightly colored Landscape with Farmhouse (1930), is displayed on a wall partially painted a vivid blue.

Nearby, Lecomte has done a wall drawing: an outline of Taussig’s last home, based on a photograph of the modernist house and atelier that she had built in Anif, a village just south of Salzburg, in 1934. It was there, the artist told me, that Taussig enjoyed the happiest, most self-determined period of her life. Before her death, she was forced to sell the house to Kajetan Mühlmann, an art historian and one of the chief plunderers of the Nazi regime. After the war, Mühlman’s wife, Poldi Wojtek – an artist and designer whose logo for the Salzburger Festspiele is still in use – refused to relinquish the property to Taussig’s heirs, until a court brokered a settlement in 1953. It was later sold and demolished.

Helene Taussig, Landschaft mit Bauernhaus (Landscape with Farmhouse), c. 1930, oil on canvas, 60.7 x 63.5 cm. © Salzburg Museum (Loan from Raiffeisenlandesbank Oberösterreich). Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com.

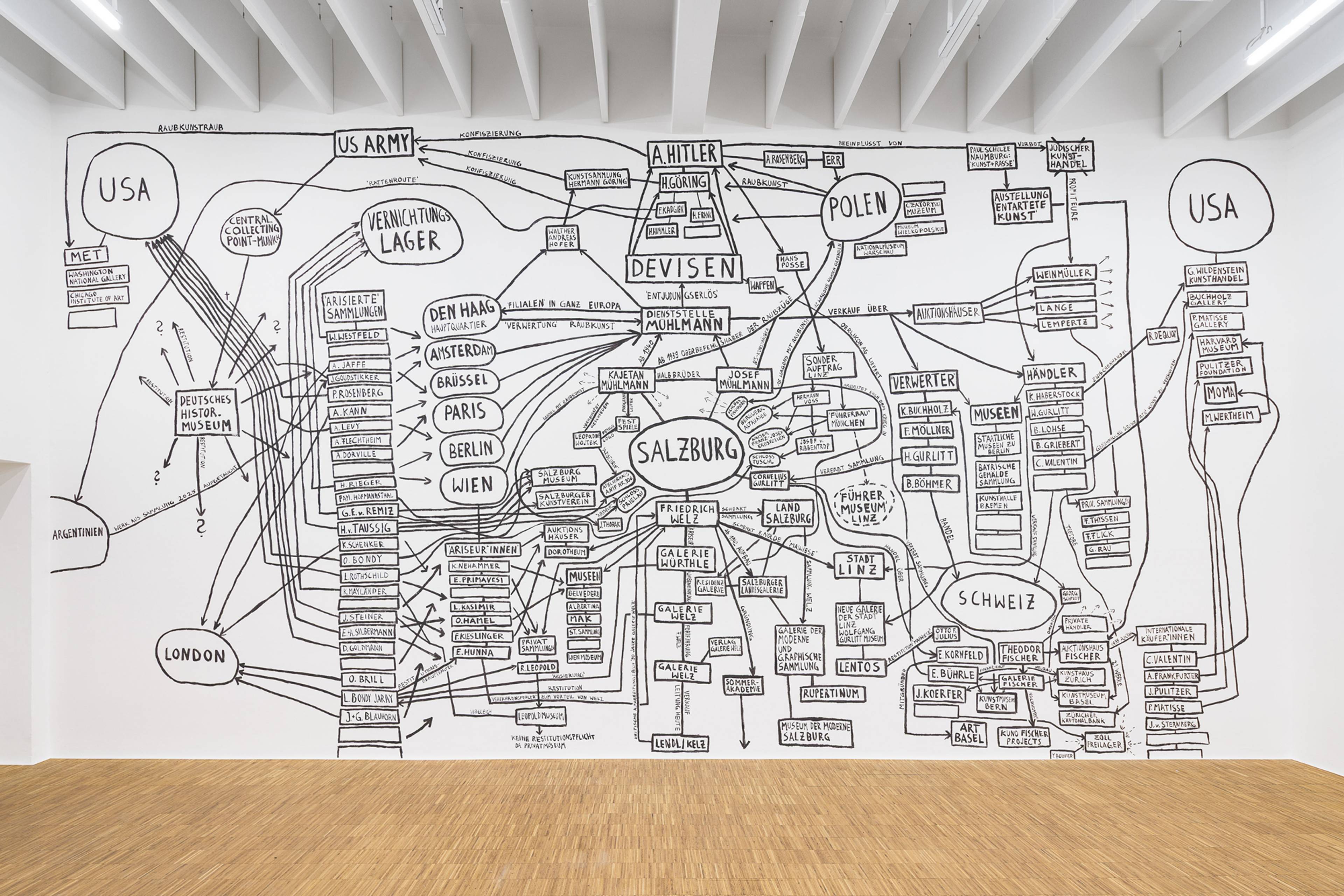

Zooming back out, Thomas Geiger has produced A Cartography of Theft, a “sociogram” of people, institutions, cities, and countries: victims, perpetrators, and recipients of Nazi plunder. Black letters and lines cover an entire wall of the gallery. Right at the top, there’s “A. Hitler,” Führer and failed artist, who had planned to build an art museum in Linz for the best of the works looted by the Nazis. This is not the only place his name appears in the exhibition. On Thun’s metal shelves, sharp-eyed viewers will notice a sticky note labelled “Hitler’s Executive”: When Thun visited the stores of the Salzburg Museum, which had recently staged an exhibition on the Austrian police under Nazi rule, one of its exhibits, a gun, was being kept on the same shelves as the objects awaiting physical restitution. As well as other familiar names – including Taussig and the Salzburg Museum – Geiger’s map contains a number of empty boxes and question marks. “Your great-grandfather should be on there,” someone told me, among so many lesser-known people and places.

At the opening of “The Museum of (Non)Restitution,” Rolinek introduced me to a retired Austrian historian, Albert Lichtblau, who interviewed my grandfather in 1993, and wound up putting me in touch with a colleague, Michael John. They both shared the research they’d done on my family, including interview recordings, which I ran through DeepL to translate. It was distressing to confront the horrific details of what my not-so-distant ancestors, like so many others, went through – a story that, until now, I had only known in vague outline (which I blame partly on my lack of German).

But I also couldn’t shake a sense of ambivalence about what has happened since. Restitution is not simply about restoring property rights, but a search for truth and justice in response to irreparable loss. Often, this has meant taking artworks out of national collections and, as in the case of my family, returning them to private ownership, where they become exchangeable assets – is this the best we can do? Besides, many works remain missing; even more troubling is the very unequal treatment of groups or nations when it comes to their restitution claims.

I can’t see my family only as victims, or as the only victims. Far from reluctant refugees, many of them were actively involved in the colonial project of Zionism, which has resulted in so much death and destruction. It’s impossible not to think, then, of those to whom restitution and the right to return may currently be a remoter prospect than ever: the Palestinians whose land and resources, from the late 19th century onwards, have been continuously expropriated by settlers and the Israeli state.

In a small, blacked-out gallery at the Kunstverein, a filmed work by Thomas Geiger quietly calls out some of the ethical ambiguities of restitution. Geiger is primarily known for series in which he initiates “conversations” with inanimate busts and other statues, reporting their responses back to the viewer. This twenty-two-minute video performance marks the first time he has chosen an abstract concept as his imaginary interlocutor: Dunkelheit (Darkness). The setting is the underground tunnels of the Altaussee salt mine, around ninety kilometers from Salzburg, where the Nazis stored thousands of looted artworks intended for the Führermuseum in Linz.

Over the course of the film, Geiger probes at the easy binarization of good versus evil – which, as his interlocutor points out, is often represented as a battle of light versus dark. We all know, even if the fiction is painful to dispel, that things are never so simple. “Museums have recently been making efforts to bring things back into the light, to scrutinize their collections in search of unjustly acquired works,” the artist says at one point. What does Darkness, whose role was to hide these stolen works, have to say about that? “Restitution is also a selective act,” she replies. “Museums and politics decide what is returned – and to whom.” The light always casts a shadow.

___

“The Museum of (Non)Restitution”

Salzburger Kunstverein

20 Sep – 16 Nov 2025

This text was written during a month-long Writer-in-Residence program at the Salzburger Kunstverein, which was awarded in partnership with Spike. Other residents were Annalise June Kamegawa, who reviewed an exhibition by Mikołaj Sobczak; and Greta Rainbow, whose essay “After the Song of the Summer” responded to dual exhibitions by Esben Weile Kjær and Laila Shawa.